Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

The two and a half year history of the First Republic of Armenia is mostly viewed in the sphere of the government’s activity: military operations, state defense, social and health issues, and foreign policy. All these were realized by the prime ministers and members of the government. In 1918-1920, Armenia was a state with a parliamentary system of government, where political parties played a pivotal role. The electoral processes in Armenia at the time have had some remarkable episodes; in some cases, they parallel today’s reality.

Following the declaration of independence on May 28, 1918, Armenia did not have an opportunity to immediately hold a parliamentary election; the unfinished war, famine, a complete blockade and instability took on a higher priority. As a transitional solution, it was decided to proportionally triple the composition of the Armenian National Council in Tbilisi to form the legislative body of the Republic of Armenia—the Parliament of Armenia.

The parliament had 46 deputies: 18 from the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), six from the Social-Democrats, six from the Armenian Populist Party (APP) and six from the Socialist-Revolutionary (SR) Party. Two more deputies were non-partisan. Additionally, eight deputies, representing the national minorities living in the territory of Armenia, were also represented: six Tatars, one Russian and one Yezidi. The first chairman of the Parliament of Armenia was Avetik Sahakyan.

In the following months, it became evident that the Parliament did not fully reflect the domestic- foreign-oriented political attitudes of Armenia, and the decision was made to hold an election, which took place in June 1919. The seemingly ordinary political event reveals the many inter-Armenian contradictions that had developed over the years.

Among those issues were the geopolitical and cultural differences between the two segments of the Armenian people—the Western Armenians and Eastern Armenians—which were becoming more acute after the declaration of independence. As a result of the 1915 Armenian Genocide and subsequent events, masses of Armenians from the Ottoman Empire had sought refuge in Eastern Armenia. They had lost everything—relatives, homes, belongings—and had barely escaped to Transcaucasia with their lives. Despite charities and the public providing material and moral support to the displaced, nevertheless a social divide was forming. Following the declaration of independence, the Western Armenians were almost completely cut off from the social and political life of the country. They did not participate in the government, did not serve in the army and were not represented in Parliament. At the beginning of 1919, a Peace Conference was convened in Paris, where the Republic of Armenia sent a delegation headed by Avetis Aharonyan to present the Armenian Question. The Western Armenians, particularly those aligned with the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU), believed that the delegation could not properly defend their cause, and so they supported the National Delegation headed by Boghos Nubar Pasha. In effect, two Armenian bodies with often significant disagreements were trying to defend the Armenian Question in Europe.

However, the main contradiction concerned Armenia itself. According to the Western Armenians, the Republic of Armenia that was created in Transcaucasia did not represent the entire Armenian people. They argued that the independent Armenia promised by the allies should be centered in Western Armenia, not in Transcaucasia; that was where the real Armenia was, where the Republic of Armenia was and that which was created on the left bank of the Araks River was called the “Ararat Republic” by Western Armenians.

“At the beginning of the existence of the Republic of Armenia, Western Armenians kept themselves isolated from state affairs. This expressed itself in many ways; there were relatively few Western Armenian officials in state institutions, Western Armenian youth avoided conscription. Western Armenians had reservations regarding other state obligations, and in general, they did not feel at ease within the republic. … In Paris, the National Delegation headed by Boghos Pasha Nubar enjoyed a higher standing among Western Armenians than the government of the Republic of Armenia. The word ‘Republic of Armenia’ was not acceptable to many; what existed was simply the ‘Ararat Republic,’” writes ARF official Simon Vratsian.

The Congress

In order to discuss the concerns of the Western Armenians and to work out a common position, the Second Congress of Western Armenians was convened in Yerevan in February 1919. The organizing group included Krikor Bulgarian, Varaztad Deroyan, Arsen Gidur and others. In a statement issued in January, the organizing committee of the congress noted that the displaced Armenians of Western Armenia are still unable to articulate and advance their goals and ideals, and to participate in their implementation: “Many have the right to speak on our behalf, but if any voice is to be heard in the fight for our just cause and the protection of our rights, that is our voice. The formulation and representation of our political ideals is being set before us right now, at this very moment. …All our subsequent problems remain unrealized; now is the time for us to forget all of them, so that we can see the great problem of history that is set before us and must be resolved.”

The Second Congress of Western Armenians adopted a resolution declaring the independence of a Free and United Armenia. Point 2 of the resolution delegated to Boghos Nubar Pasha the authority to convene the first session of Free and United Armenia. Point 5 instructed the executive body of the Congress to declare the independence of United Armenia together with the Parliament and Government of the Ararat Republic, and to “participate in the existing state and legislative institutions to bring about the realization of a nationwide union.”

The Congress, as is apparent, was not solving the problem of uniting the two Armenian poles. The Western Armenians continued to trust Boghos Nubar Pasha, although it seems they were also willing to cooperate with state bodies on more equal terms.

Calling the Election

There were also many contradictions within the Parliament of Armenia. The Armenian Populist Party (APP), the Social Democrats, and the Socialist-Revolutionaries (SR) were the main opposition, and they criticized the ARF for almost everything. On the evening of February 28, 1919, the citizens present in the Parliament hall started a commotion, expressing their protest against the efforts of the executive body. “As soon as the session was announced open, exclamations were heard from the public: ‘We do not want such a parliament,’ ‘We demand an elected parliament,’ ‘Self-proclaimed deputies be gone,’” the Zang newspaper wrote.

The Chairman of the Parliament refused to continue the session under these conditions. The Deputy Chairman Davit Zubyan, an SR, stepped into the role, but the citizens did not calm down. They physically pulled Zubyan down from the pulpit. The session was terminated.

The SRs blamed the ARF for the incident, saying that “after long fluctuations, the ARF finally showed its true colours… it had the courage to fight openly with the Socialist Party in Parliament.” Of course, the Yerevan Committee of the ARF denied this accusation, but the incident once again demonstrated that the Parliament had completely exhausted itself.

On March 31, 1919, a new electoral law of the Republic of Armenia was adopted, which envisaged holding the forthcoming election. According to the law, the new Parliament of Armenia was to be elected by proportional representation using closed candidate lists. Secret balloting, still a relatively new concept at the time, would ensure citizens could vote their conscience. All citizens over the age of 20, both male and female, were given the right to vote (in the United States, the 19th amendment granting women’s suffrage had not yet been ratified at that point). The new Parliament was to have 80 deputies.

“Central, provincial, regional, municipal, rural and local election committees were set up to conduct the election. The central committee was appointed by the Parliament of Armenia, and the rest, by committees superior to them.”

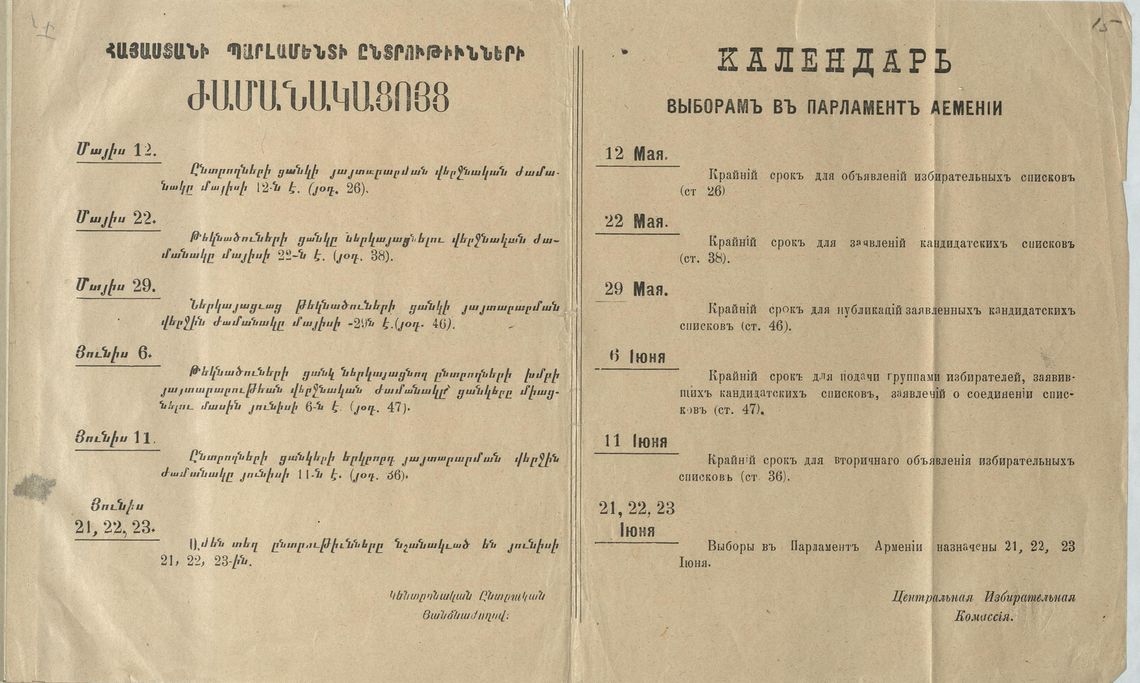

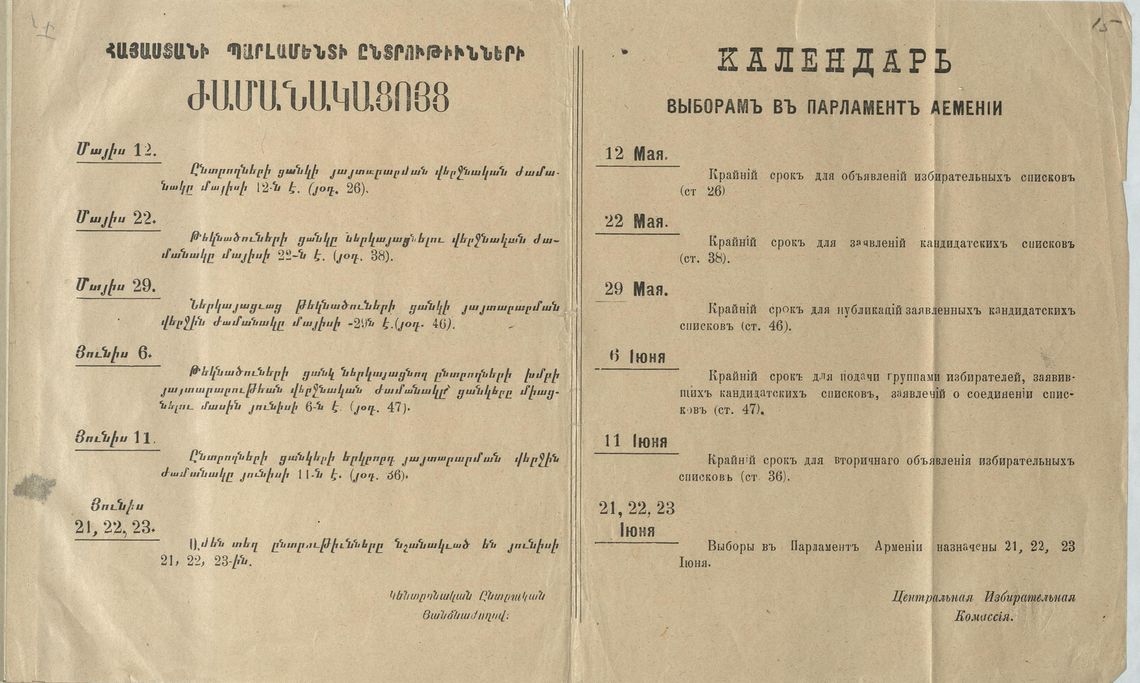

At the end of April 1919, the Parliament of Armenia suspended its work for a month, handing over its powers to the Government of Armenia. The electoral committee compiled the schedule of the preparatory period for the election, according to which the final lists of voters would be published by May 12, and the final lists of candidates by May 22. The government allocated 200,000 rubles to the electoral committee to organize these events.

The Armenian parliament, which was a temporary institution, voted for and adopted the electoral law on the composition of the parliament in its final sessions. Simultaneously, it decided the day of the election—June 21—and appointed S. Khachatryan to be the chairman of the Central Electoral Committee.

The May 28 Act and the Social Divide

In April 1919, it was decided to celebrate the anniversary of the proclamation of the independence of the Republic of Armenia with great pomp and circumstance. At the same time, a special statement was to be adopted on May 28, which was to clarify the government’s position on Armenia’s independence and satisfy the concerns of Western Armenians.

On May 27, 1919, the government decided to convene a special session on May 28, which was to be attended by parliamentary deputies and the 12 members of the Executive Body established at the Second Congress of Western Armenians. On Independence Day, following the solemn ceremony, Prime Minister Alexander Khatisyan read the statement known as the “May 28 Act.” With this declaration, the Armenian government announced that it was committed to protecting the interests of a united, independent Armenia, including Western Armenia:

“Now, by carrying out this Act of unification and independence of ancestral Armenian territory located in Transcaucasia and within the borders of the Ottoman Empire, the Government of Armenia declares that it is the government of the United Republic of Armenia.”

Following the announcement, the 12 members of the Western Armenian Executive Body sat next to the parliamentary deputies of Armenia in solidarity.

Although Simon Vratsian writes that the unification ceremony “was greeted with enthusiastic applause by the public,” in reality, it caused deep dissatisfaction for some political forces and further divided society. It would also influence the course of the parliamentary election.

“Bon Voyage”

On June 4, 1919, the Assembly convened its last session, where the Social Democrats criticized the ARF, and called the May 28 Act a coup d’état against parliament. According to them, by May 28, the term of office given by the parliament to the Government had already expired, and that the Government did not have the authority to make the declaration. The Social Democrats declared that the government “propped up by the ARF, is dictatorial, does not respect the laws, acts against the constitutional spirit.” In demonstration, they then left the hall. As they shuffled out, mocking exclamations of “bon voyage” were heard from the hall.

Next, the Armenian Populist Party made a statement in the Assembly, also referring to the May 28 Act and the entry of 12 Western Armenian deputies into the parliament as a “coup d’état, a constitutional violation, a big blow to the constitution.” The APP stated that only the mixed session of the Armenian Conference in Paris and the Armenian Parliament had the right to adopt such a declaration. In protest, the APP recalled its ministers from the Government, left the hall and announced that it will not participate in the parliamentary election.

Simon Vratsian writes that, on the day of the declaration of Independence, the Zhoghovurd newspaper of the Armenian Populist Party was excitedly writing “Long Live United, Independent and Free Armenia,” but just a few days later, they had changed their position. According to him, during the May celebrations, Samson Harutyunyan, a member of the Armenian Populist Party, was not in Yerevan. Once he returned, the position of the party changed dramatically. “It soon became known that the Populists’ move was dictated from Paris,” writes Vratsian.

In Tbilisi, the Armenian Populist Party newspaper The People’s Voice published a statement on June 11, entitled “We are complaining, listen.” It clarifies why the Populist Party decided to boycott the parliamentary election. This text, written on behalf of the Western Armenians, referred in detail to the events of 1917-1919 and condemned the “incompetence and short-sightedness” of the ARF. At the same time, they expressed hope that the Armenian Populist Party would reconsider and clarify its position on the events taking place in Armenia and the May 28 Act.

“According to the slogan of the May 28 Act, you must form an interim joint government for a united and independent Armenia. To this end, the Government of the Caucasian Armenia should immediately enter into negotiations with the delegation of Boghos Nubar and form a joint interim government and parliament by mutual agreement, to which it will hand over the right to conduct current affairs, until the people of United Armenia have the opportunity to establish their legitimate government,” the newspaper wrote.

The ARF rejected the proposal to form a joint government with the National Delegation headed by Boghos Nubar. Subsequently, in early June, the APP announced its protest and exited the coalition. APP ministers also left the Government. On June 8, 1919, Zhoghovurd reported that the APP would not run in the parliamentary election, urging residents to also boycott the election by refusing to vote.

“Citizens, do not participate in the upcoming parliamentary election, thus expressing your fervent protest against the ARF’s May 28 Act, which dealt a severe blow to the principles of law and popular representation. ‘Long live Free and United Armenia! Long live parliamentarianism! Down with the Dashnak oligarchy!” the newspaper wrote.

Some Western Armenians were also dissatisfied with the May 28 Act and the admission of the 12 members of the Executive Body into the parliament. The problem was that, following the February Congress, the issue of the participation of Western Armenians in the parliamentary election was discussed many times, and they had almost always come to the conclusion that they do not represent all Western Armenians. The 12 members of the Executive Body were charged with serious accusations. On June 12, 1919, the Van-Tosp newspaper called them “parasites,” writing that the Executive Body did not want to hear the people’s complaints and “applied to this parliament to also be given a warm corner.” For several days “Down with the 12 Turkish-Armenian parasites that entered the parliament” was printed in big letters in the pages of Van-Tosp. Soon, the Ramkavars and a number of Western Armenian organizations joined the call to protest the parliamentary election.

In effect, the Second Congress of the Western Armenians and the May 28 Act failed to unite society, and to some extent also deepened the chasm.

“Do not go near a ballot box. No votes for any list.” Van-Tosp, 1919.

“Citizens! Do not participate in the elections! Boycott the illegal elections! Do not vote for political opportunists who have abused and mocked your misery and black days.” Van-Tosp, 1919.

Thus, the following parties/lists were registered for the parliamentary election:

N 1 – Armenian Revolutionary Federation, 120 candidates

N 2 – Armenian Populist Party, 65 candidates[1]

N 3 – Socialist-Revolutionaries (SR) Party, 35 candidates

N 4 – Kurdish list, 2 candidates

N 5 – List of Assyrian National Council, 3 candidates

N 6 – List of non-partisan Peasants’ Union, 18 candidates

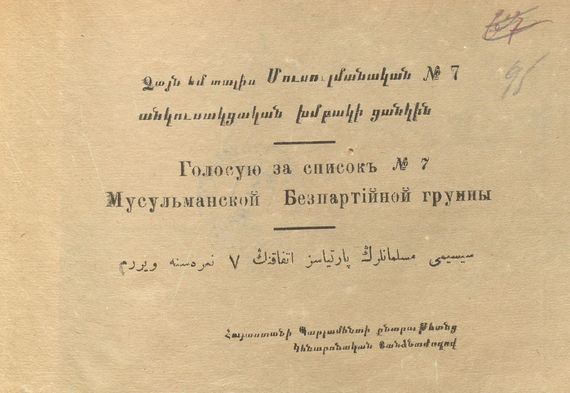

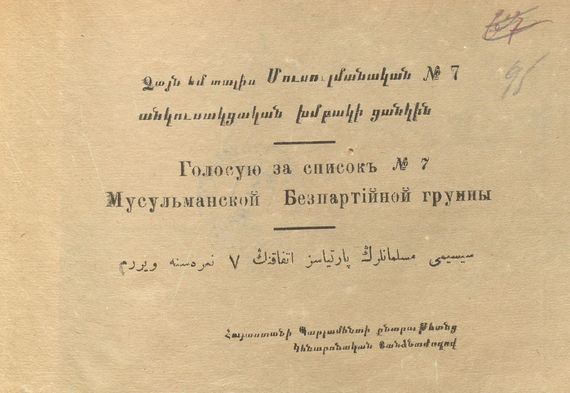

N 7 – Muslims List