On October 16, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan handed in his resignation and it is now an almost foregone conclusion that snap parliamentary elections will take place in December of this year. These elections must ensure the completion of the revolutionary changes in Armenia’s political landscape.

Contemplations about who will be the winner of the parliamentary elections are pointless. The Yerevan municipal elections were a clear indication of the immense advantage the Civil Contract Party continues to have over other political forces. The only issue is who the second and third political forces to enter parliament will be and in general who among them will be the country’s opposition.

The Street as Opposition

The issue of a political opposition has been in discussion over the last five months, be it in public discourse, during political debates and among citizens trying to understand the course of political developments.

The necessity of an opposition in a healthy political system is self-evident. It was the lack of a strong, institutionalized, real opposition that degraded Armenia’s pre-revolutionary political landscape. One of the two important institutions supporting the classical system of government-opposition duality was missing. Since the beginning of the 2010s, with the weakening of the Armenian National Congress, political forces that had declared themselves as opposition were either in collusion with the authorities, were appointed by them or being in the opposition was a tactical means to, every once in awhile, secure certain appointments from the Republican Party of Armenia (RPA). The true opposition was weak and its prospects under the amended Electoral Code, as the April 2017 elections illustrated, were bleak.

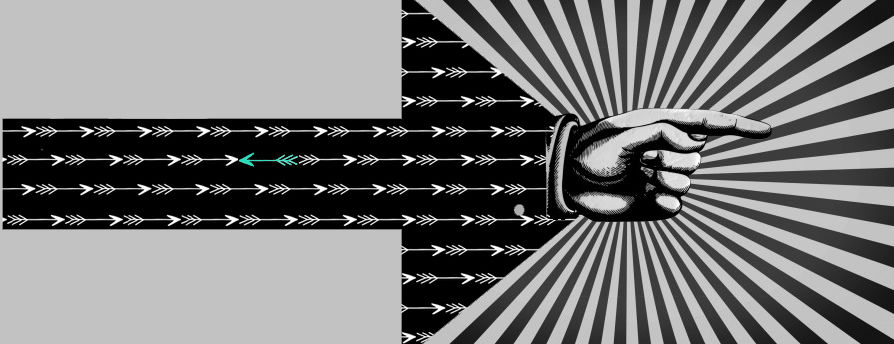

During the Velvet Revolution, it was the Street that stood in for this missing pillar. The street became the opposition and the party affiliation of the leaders of the movement was irrelevant to the people. The street won because it was an absolute opposition, it was not against certain aspects, it opposed the entirety of the existing political system, its traditions, its mode of operation and its language.

Following the victory of the revolution, its leaders became the government. The logic of the revolution granted them the “unlimited resource of trust.” While this provides an exceedingly large potential and ability to implement fundamental changes, at the same time, it’s ripe with considerable danger. In the absence of a healthy opposition, the unconditional, sometimes almost unshakeable support of society coupled with the inexperience of the governing team can result in undesirable consequences.

The Dictate of Public Opinion

Conditions for the formation of an opposition at this stage are, of course, unfavorable.

First, the fact that the RPA is currently in the role of the opposition has been daunting for many other forces who do not agree with certain policies of the government. A critique of the government can today be viewed in a broad sense as support for the RPA’s counter revolution. Even when the RPA acts as a classical opposition, having been the ruling party for many years, it has lost credibility and any given issue voiced by the party, any critique, even if sometimes very founded and true, is perceived as an attempt at retribution, a false accusation and never as an honest, well intentioned citing of mistakes. Under these conditions, the internal critic in me and many others like myself suggests that it is better to wait for the complete institualization of the revolution before we criticize the revolutionary authorities, and at this stage, that would be the parliamentary elections.

On the other had, this extreme polarization has created a situation where any opposition succumbs to the ruthless pressure of public opinion from the very moment of inception. In his now infamous speech Hayk Marutyan [current Mayor of Yerevan], with his analogy of “black and white” forces, unwillingly exposed this reality. And public opinion, which today supports Nikol Pashinyan to the point of idolatry, is unbelievably potent. Under conditions of a democratic government, pubilc opinion can become a powerful dictator.

French historian and political theorist Alexis De Tocqueville, having lived in America between 1835-40, published his acclaimed study titled “Democracy in America.” In the chapter, “Unlimited Power of the Majority” he says that a potential democracy is more dangerous for freedom than a monarchy or the rule of the aristocracy. “The authority of a king is purely physical, and it controls the actions of the subject without subduing his private will; but the majority possesses a power which is physical and moral at the same time; it acts upon the will as well as upon the actions of men, and it represses not only all contest, but all controversy. I know no country in which there is so little true independence of mind and freedom of discussion as in America.” Tocqueville, in particular spoke about the “tyranny of the majority” against unpopular views. This concept is further elaborated by Tocqueville’s colleague and correspondent John Stuart Mill’s “On Liberty” (1859) “… reflecting persons perceived that when society is itself the tyrant – society collectively, over the separate individuals who compose it – its means of tyrannizing are not restricted to the acts which it may do by the hands of its political functionaries… it practices a social tyranny more formidable than many kinds of political oppression, since, though not usually upheld by such extreme penalties, it leaves fewer means of escape, penetrating much more deeply into the details of life, and enslaving the soul itself.”

Since Serzh Sargsyan’s authoritarian regime never enjoyed the support of the vast segment of society, it could never evolve into the tyranny of the majority, it remained the repression of one person, or a group of people or power structures.

Is There a Way Out?

Under these circumstances, should we expect the emergence of political forces which support different viewpoints and would dare openly criticize Pashinyan’s political course with the understanding that they will unequivocally be perceived as being on the same side of the barricades as the RPA? And even if such forces emerge, will they succeed, which at least by today’s measures means making it to parliament?

One thing is for certain, the country needs a diversity of opinions in parliament and a diversified political landscape. Today’s authorities who must have learned from the mistakes of their predecessors and by nature are more democratic, should understand that. But it still remains unclear how that diversity might come into existence. Objectively, Nikol Pashinyan’s team prevails in the minds and the hearts of the people. How can the electorate be convinced to vote for other political forces in the upcoming elections?

In this case, and as absurd as it may seem, the only solution would be a call by the enormously popular Acting Prime Minister himself to form a pluralistic parliament that is essential to the country.