Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan, who really did test positive today.

COVID-19 has been a permanent fixture among international headlines for the past two years. Most recently, reinforced restrictions associated with the Omicron variant have sparked renewed protests, most notably in Canada and France. Armenia never faced COVID-19 street protests, but various emergency measures have met a different kind of resistance.

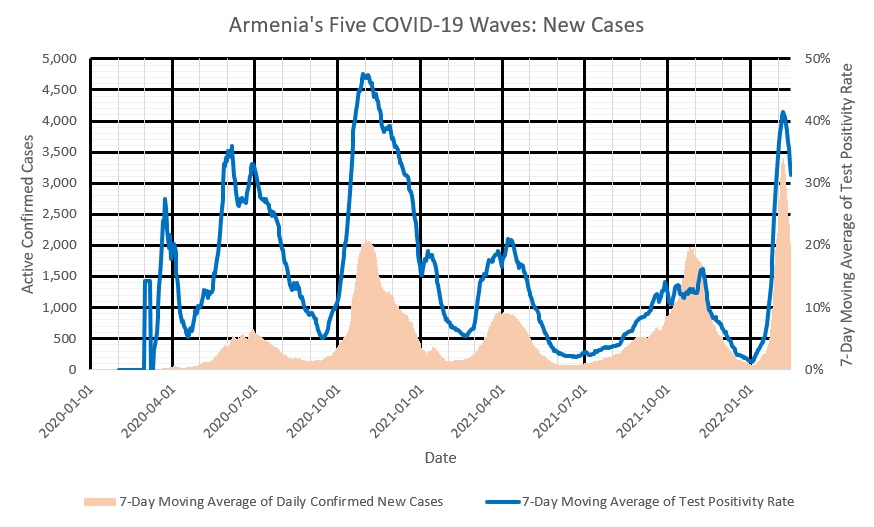

Worldwide, the most commonly reported COVID-19 data points are daily and cumulative cases, as confirmed by tests; these announcements feed daily headlines. For Armenia, this data reveals five major waves of COVID-19 infection within the country, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. COVID-19 Case Counts and Test Positivity Rate in Armenia

Relying on positive test results, however, comes with limitations. It is important to remember that these are only “confirmed” cases; people who have COVID-19 but do not get tested are not included. A seven-day moving average of the daily case data provides a more general picture, smoothing out factors such as people waiting different amounts of time to get tested and fewer tests being conducted on Sundays. Also, considering the positive test rate together with the confirmed cases helps to gauge how many cases are going undetected, as Figure 1 does.

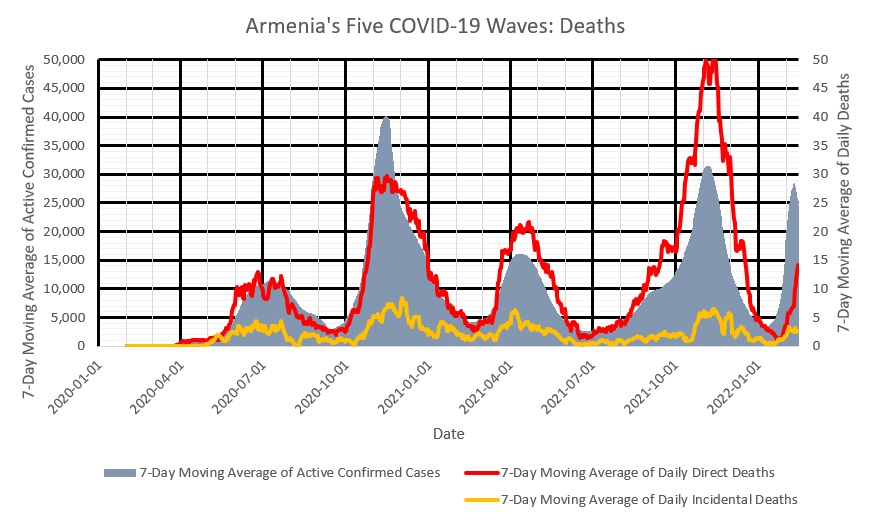

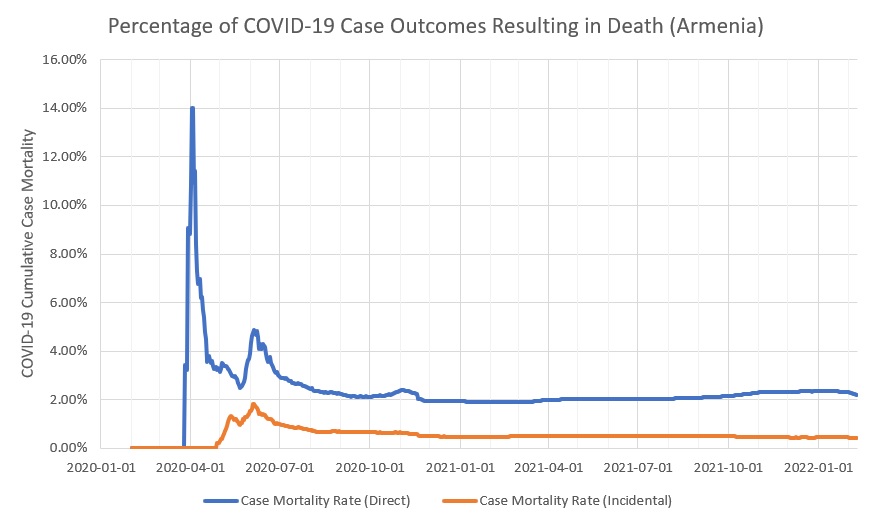

Another limitation is that not all cases are equal. Some patients never show any symptoms at all (and undoubtedly some unknowable number among them are false positives), some only go through very mild symptoms that do not require any medical treatment. The more severe cases require hospitalization and could end in death, especially among older patients or those with immune system disorders. Segmented case data by severity is not publicly available. As a proxy for the severity of Armenia’s five COVID-19 waves, death data can be used instead. Figure 2 confirms that severity of infection is also observed in five distinct waves, the last of which is currently playing out. Since the very beginning of the pandemic, Armenia has reported incidental COVID-19 deaths (cases where the patient happened to have COVID-19 but it was not the primary cause of death) separately from direct deaths, where a patient was specifically hospitalized due to complications arising from COVID-19 infection (though other comorbidities may still have impacted their death). These two totals are shown separately in Figure 2.

Figure 2. COVID-19 Deaths (Direct and Incidental) in Armenia

It is worth looking into each of these waves and their associated social restrictions to understand the evolution of sociological behavior and the limits of public policy to impact it.

The Zeroth Wave: (February 24, 2020 – April 14, 2020)

Although the data reveals five waves, a lot happened before the first wave really got going. In fact, it was the period with the most extreme restrictions; even though, in hindsight, the number of cases was minuscule. Let’s label the period from February 24 to April 15 the “zeroth wave”.

February 24 marked the first public policy reaction by the government that affected some citizens’ daily lives. On that day, Armenia’s border with Iran was temporarily shut down and regular flights were canceled due to the southern neighbor being identified as a global hotspot for COVID-19. A few charter flights were arranged to bring back Armenian citizens. One passenger on one of those charter flights was found to have COVID-19 on March 1, 2020, marking Armenia’s first confirmed case.

Spring Break was moved up one week to reduce the risk of transmission at schools. After a week of no new recorded cases, schools re-opened on March 9. However, three additional cases were recorded on March 11, setting off a domino of restrictions.

A State of Emergency was declared on March 16, with Deputy Prime Minister Tigran Avinyan being appointed Warden (Paret) of the Special Commission on the State of Emergency, which was given leverage to rule by decree. Early restrictions included a ban on media reporting any information about the pandemic that did not originate from the government. The media ban was worded overly broadly such that it would technically have been illegal to quote the World Health Organization (WHO) unless the government also had released that information itself. Fortunately, there was a verbal backlash, and the media ban was quickly lifted.

From April 1 to April 14, a two-week severe lockdown was instituted. Only essential industries were allowed to continue operations. Other citizens were expected to stay in their homes; they could be stopped by police and fined for leaving their homes without valid justification (such as grocery shopping). Checkpoints were set up on roads connecting Armenia’s different regions to restrict intra-country travel. School was moved online with little preparation.

These severe curtailments on mobility were enacted in many different countries. While they did buy some time for experts to study the nature of the virus and prepare for an upsurge in patients, a recent study from John Hopkins University found that lockdowns had a negligible impact on COVID-19 mortality, only reducing deaths by about 0.2%. The costs of the lockdown began to mount quickly, however, as Armenia announced 22 different social support programs to offset the economic impact of not allowing people to go to work.

In addition, all phone metadata was ordered to be handed over to the Warden to facilitate contact tracing. When a person tested positive, everyone they had spoken to on the phone recently were also called in order to check if they had come in physical contact. If they had, they would also undergo testing and a 14-day quarantine. The measure was criticized for being an unnecessarily broad overreach for the intended purpose. It paralleled a pre-pandemic proposal for the government to access telecommunication metadata that had arisen in October 2019 but had been canned due to criticism. The hard drives that contained this personal data were supposedly destroyed in September 2020, but it is impossible to know whether or not a copy had been made beforehand and kept.

During the 2020 Artsakh War, an Azerbaijani hacker group released the names and phone numbers of virtually every Armenian resident. However, a clear tie between the hack and the COVID-related collection of data has not been confirmed.

By April 14, 2020, a total of 17 COVID-19 deaths had been reported.

The First Wave: (April 15, 2020 – August 31, 2020)

Starting on April 15, the number of businesses permitted to operate was expanded. It wasn’t until May 15, however, that the lockdown ended for good and average citizens were allowed to freely leave their homes again. With this greater level of social interaction, case counts began to rise quickly. As Armenian COVID-19 figures exceeded those of its South Caucasus neighbors, there were some initial doubts about whether the government had ended the lockdown too early. In hindsight, though, it was unquestionably the right move.

Hospital beds did grow scarce as the numbers increased, but the demand was handled by dedicating additional hospitals to COVID-19 patients and discontinuing the practice of keeping asymptomatic (and then mildly symptomatic) patients in the hospital for 14 days, to make room for those who actually needed care.

A mandate to wear a mask, even while outdoors, was imposed, enforceable by a fine that was initially set at 100,000 AMD (more than half the average monthly wage). This fine was later reduced to 10,000 AMD. In response to a Freedom of Information request, Armenian Police reported that 99,574 fines for not wearing a mask had been levied by August 27, 2020.

Case counts began to decline on their own in July. Daily death averages peaked at around 10, but they were down to five by August. It seemed like perhaps Armenia was reaching some level of herd immunity, but those interpretations were shattered with the outbreak of the 2020 Artsakh War on September 27.

The Second Wave: (September 1, 2020 – February 28, 2021)

Even before the war started, case counts began to climb slowly in early September as the new school year brought greater indoor social interaction among local communities. But it was in October that things really began to spike. The wartime relief effort of caring for displaced families and sending supplies to the troops cast COVID-19 concerns to the backburner in Armenians’ psyche (where it has remained to this day). Although the mask mandate remained on paper, which police officer was going to dare issue a fine for such a trivial matter when there were much more serious problems at hand?

Sadly, COVID-19 deaths also rose to an average of 30 per day. In addition to the 3,812 Armenian casualties of the 2020 Artsakh War, an additional 1,865 died of COVID-19 between October and December 2020. It wasn’t until January 2021 that the second wave subsided.

After the war, there were street protests calling for the resignation of Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan. Like the mask mandate, there were rules restricting protests, especially under the martial law regime that lasted much longer than the war itself, but they were practically unenforceable. Using force to break up the protests would have shattered the injured legitimacy of the Prime Minister, and he wisely chose against it.

The Third Wave: (March 1, 2021 – June 30, 2021)

On March 1, 2021, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan called his supporters to rally in Yerevan’s Republic Square as a show of support. Military officials had just demanded his resignation, an event he labeled as a coup attempt. Over 20,000 showed up, including those from different cities, and a third COVID-19 wave followed in its wake.

The third wave was not as large as the second. Less people were infected overall and peak average deaths were at 20 per day instead of 30. Fortunately, by the time of the early election on June 20, 2021—another event that had the potential to be a nationwide super spreader—active cases were at record lows.

With the election on the horizon, the outdoor mask mandate was lifted—just ahead of the Yerevan Wine Days street festival on June 4, 2021. It had long since stopped being enforced anyway. The announcement had an unintended consequence, however. Immediately before, it was still common for businesses in Downtown Yerevan to ask customers to wear their mask when indoors at a store or a bank. After the announcement, it was still technically a finable offense to not wear a mask indoors, but both outdoor and indoor mask-wearing stopped in Yerevan. Outside Yerevan, nobody had been wearing masks for a long time already; in fact, wearing a mask outside Yerevan would attract stares and build social pressure to remove it.

It was during the third wave that vaccines became available in Armenia. At first, they were only available to those over 65 or in another high-risk group. However, after a slow take up at polyclinics and looming vaccine expiration dates, it was decided to offer the COVID-19 vaccine to anyone that wanted one. Mobile vaccination points almost immediately increased the rate of doses administered from 30 per day to over 1,000 per day.

Even as the vaccine delivery system became more efficient, overcoming vaccine hesitancy was a separate challenge. A previous EVN Report article has already covered the impact of revelations of rare side effects associated with the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine, which were the first to be widely available in Armenia. As cases had already begun dropping in Armenia by mid-April, when the first vaccines were delivered, there was not a sense of urgency to be one of the first to try a vaccine that had already been discontinued (or never approved) in several other countries. By the end of June 2021, about 60,000 first doses and 20,000 second doses had been administered in the country. Armenia’s population is estimated at just under 3 million.

The Fourth (Delta) Wave: (July 1, 2021 – December 31, 2021)

The fourth wave began to climb much more gradually than the first three, again reducing the sense of urgency to get vaccinated. With the delta variant proving to be more deadly than previous versions, the Government decided Armenians would not continue to have much of a choice in the matter. In August 2021, it was announced that all public and private sector employees would need to be vaccinated by October 1 or pay for biweekly PCR testing “out of their own pocket.” A PCR test in Armenia runs around 10,000 AMD ($20). The minimum monthly wage is 68,000 AMD. The average net monthly income was around 150,000 AMD in October 2021. The directive expressly prohibited businesses from covering the testing costs for their employees, a provision that was later struck down by the Constitutional Court only after it had already come into effect.

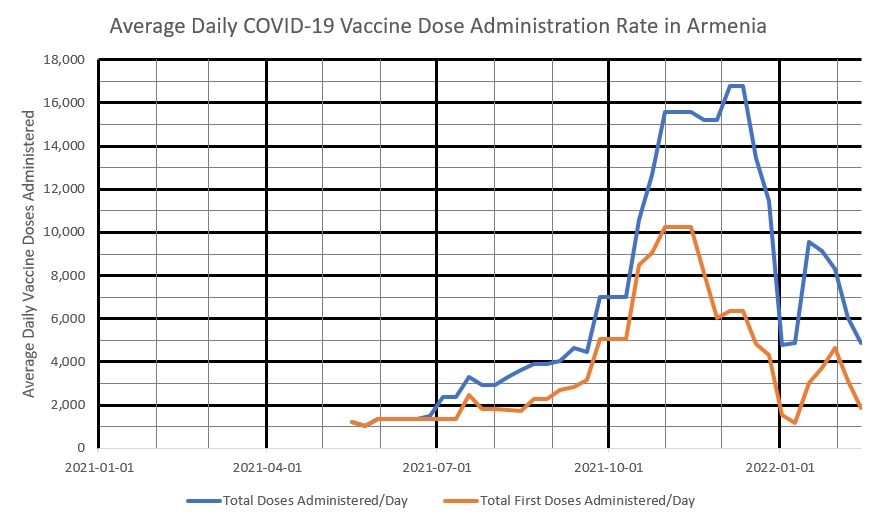

Figure 3 shows the number of vaccinations performed per day. The take up of first doses clearly increased leading up to the October 1 deadline. It was not until after September 30, when the Moderna vaccine first became available to Armenians through a donation from Lithuania (and later Norway and Slovakia), that the daily figures doubled, however. The newfound acceptance of the vaccine coincided with unprecedented daily death figures, as shown in Figure 2 near the beginning of the article.

Figure 3. Rate of Vaccine Doses Delivered in Armenia over Time

The delta wave was deadlier than anything that came before it. Death counts were averaging 50 per day at the peak in early November. The outdoor mask mandate was reinstituted, but in practice, Police took a gentler approach. At high traffic areas like Northern Avenue and Republic Square in Downtown Yerevan, Police would approach unmasked pedestrians and ask them to cover up. Usually, people had a mask on them and avoided a fine by complying. While wearing a mask outdoors actually does little to reduce transmission, the policy actually reinvigorated enforcement indoors, which had technically always been required. Employees at stores would once again ask people to wear a mask upon entering, usually offering to sell one if necessary.

Between July 1 and December 31, a period when vaccines were widely available, a total of 3,458 people died of COVID-19 in Armenia, accounting for 43% of the total up to that time. A further 407 died having contracted COVID-19 but not as a direct result of the virus. Figure 4 shows that direct case mortality rose from 2.0% to 2.3%.

Figure 4. Cumulative COVID-19 Case Mortality in Armenia

Fortunately, the severity of the delta wave fell off quickly after hitting its peak. By December 17, the outdoor mask mandate was lifted and Armenians were able to spend the holidays with record low levels of active cases.

The Fifth (Omicron) Wave: (January 1, 2022 – present)

Health Minister Anahit Avanesyan had announced on November 29, 2021, that a vaccine passport system was planned to be implemented on January 1, 2022. Only those who could provide documentation of vaccination or a recent negative PCR test would be able to enter restaurants and entertainment venues. However, in light of the declining caseload, that January 1 timeline was not kept.

A minister’s decision was signed on January 5 (but not publicly announced until January 10) that the vaccine passport system would be rolled out to restaurants, bars, gyms and cultural venues such as concert halls and museums on January 22. Businesses would not need to purchase any special equipment. Customers could use the ArMed app to display a QR code matched with a photo to provide evidence of vaccination or a negative test and thus be allowed to enter. The measure did not apply to minors under 18, those with an official certificate confirming pregnancy and those who had tested positive less than 90 days earlier and then consequently recovered.

By this time, the Omicron variant had spread worldwide. Although it generally causes milder symptoms, it was able to spread much more quickly, including to vaccinated people. Given the circumstances, it is difficult to explain what the intended purpose of a vaccine passport system is. It doesn’t protect the vaccinated, since other vaccinated people can still spread the virus to them. It doesn’t protect the unvaccinated, since it only applies to a narrow range of businesses and excludes others like public transportation and retail stores.

An analysis by The Economist reveals what vaccine passports are intended for: making life more difficult for the unvaccinated so that they surrender. Figure 3 does show a sharp uptick in first dose take up after the January 10 announcement. However, another explanation could be that some people delayed getting their vaccine in the last week of December and first week of January so that they would not have to deal with the temporary muscle aches while entertaining guests.

Omicron did eventually hit Armenia with a fifth wave. Deaths are still trending up, although case counts have already begun to decline. Due to the milder nature of this variant, Health Minister Anahit Avanesyan said that only 5-6% of cases required hospitalization. Citizens who test positive were considered automatically recovered if they did not seek hospitalization 7 days or 10 days after the positive test, for vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals respectively. As of January 27, 2022, she said that 45.3% of Armenians had received their first dose and 37% had received their second dose of the vaccine.

Targeting employees and restaurant patrons leaves out the most vulnerable demographic, though: seniors. Avanesyan said that the vaccination rate among those over age 65 is closer to 18-19% (as of January 27). While vaccination was not able to completely prevent infection with Omicron, it was reported that it provided protection against severe disease.

Vaccine Passports on Borrowed Time

Vaccine passports were first proposed as a way to waive the 14-day quarantine that international travelers were subject to when crossing borders, i.e. to provide greater convenience to people. Once available, they were quickly used to artificially inconvenience people who had already been most resistant to accepting a vaccine.

Other countries are past their own Omicron peaks and have been quick to announce an end to their vaccine passport schemes, especially as mounting protests drive up the political cost of maintaining them. Just a few weeks ago, there were suggestions that a vaccine passport would expire six months after one’s most recent booster dose. In Germany, there are some venues that already require a third dose or a negative PCR test in addition to the initial two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine in order to enter. Now, it seems clear that requiring every person to get a new vaccine dose every six months is not viable.

In Armenia, like the outdoor mask mandates that don’t have a scientific basis, the vaccine passport has been a flop. There may be a handful of conscientious restauranteurs that ask for them, but the vast majority do not risk shooing away a potential customer.

In a recent poll by the International Republican Institute, COVID-19 did not make the top 16 issues that Armenians are concerned about. Instead of sending out inspectors to fine businesses that have been through enough over the last two years already, three and a half weeks after they were brought in, it seems just a matter of time before vaccine passports are lifted here, too.