A recreation of two posters from the Karabakh Movement: Air filled rubber gloves representing elections, originally with the inscription, “The deputy was elected by a pressing majority” and the word Constitution in Russian that eventually becomes only one letter, “я” meaning “I” (Form Harutyun Marutyan’s archives).

In 1989, social and political upheavals shook one Eastern European country after another, something historians would later characterize as “Eastern European Revolutions” or simply the “Revolutions of 1989.” The Berlin Wall, in the heart of Europe, which had symbolized the dividing line between the “democratic” West and the “communist” East, came down. With this, the socialist camp disintegrated; within two years the Soviet Empire disappeared from the world map; the ghost of communism, roaming in Europe from the times of Marx and Engels was confined to the pages of history and merely became the subject of study.

A year before these developments, a powerful democratic movement began in the smallest of the Soviet Republics, in Soviet Armenia. In academic literature, with a few exceptions, it is considered only within the context of what was seen as an “ethno-territorial” conflict, an Armenian-Azerbaijani one. In my opinion, what took place in Armenia as part of the Karabakh Movement, was the first of the Eastern European revolutions and as such, played a considerable role in the democratization of Soviet society, had a substantial part in the deconstruction of the Soviet Union and consequently the elimination of the threat of communism. As the first, it was not regarded or perceived as a revolution, and as such, remained obscure in academic circles, whereas the formulations of the “unrecognized revolution”[1] can shed new light on the study and evaluation of democracies that emerged in Eastern Europe in the late 20th century.

However, let’s start at the beginning.

In their search of the roots of the Karabakh issue, Armenian historians go back in time stretching from a century to a several hundred years. This is normal depending on the context the conflict is being regarded in. But as far as the 1988 Movement is concerned, the base of the problem starts with the establishment of the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) as a separate territorial unit. This was the July 5, 1921 decision of the plenum of the Caucasus Bureau of the Communist (Bolshevik) Party of Russia, a decision, ratified without discussion or a vote, to “leave Nagorno Karabakh within the borders of the Azerbaijani SSR and grant it wide regional autonomy,” disregarding the fact that at the time, Armenians constituted 94.73 percent [2] of the region’s population. Around six decades later, according to a 1979 census, Armenians constituted only 75.9 percent of the population of NKAO, registering an almost 20 percent decrease. In 1939-1979, the Armenian population of Karabakh decreased by 7.3 percent and the Azerbaijani population increased 2.6 times. Researchers believe the mass outflow of Armenians from NKAO as well as Azerbaijan proper was the result of the implementation of an economic, social and cultural policy, which created preconditions prompting Armenians to permanently leave. [3]

In the mid-1980s, the leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) declared the policy of Perestroika (reconstruction), democratization and Glasnost (openness). This, following other developments, greatly contributed to the February 20,1988 resolution of the Regional Soviet of the People’s Deputies of NKAO, to leave Azerbaijani SSR and join the Armenian SSR. On the same day, mass protests with the participation of hundreds of thousands, took place in Yerevan. Some time later, as the protest drew in almost all layers of Armenian society, the protests became known as the “Karabakh Movement” (February 1988 – August 1990). An analysis of the Movement shows that the Karabakh issue, as the ultimate political priority of the Movement, often served as the backbone for revealing and trying to resolve many other vital issues concerning society in Armenia. One can notice two parallel, interconnected directions: the struggle for national-liberation and the realization of democratic reformation. It gradually became clear that the success of the national liberation struggle, i.e. the solution to the Karabakh issue, depended on the accomplishments of the democratic reformation process.

The most distinctive characteristic of the Karabakh Movement was that it was pan-national. The only social class that in one way or another opposed the developments of the Movement was the nomenclature bureaucratic elite of the Communist Party of Armenia. They clearly understood that democratic transformation was the path chosen by the Movement to solve the issue of Karabakh’s reunification with Armenia. In this regard, the Movement did not become pan-national overnight. Other than the February 1988 decision not to support Karabakh’s right to self-determination, another contributing factor was the behavior of the Union authorites and the leadership of the Republic which was clearly demonstrated by the following actions: the Party media and television news program “Vremya” were reporting about the developments in NKAO and Yerevan in a manner, according to Armenian citizens, that was incompatible with the truth and incomplete, and describing them as “extremist.” Secondly, CPSU Central Committee Bureau Candidate Vladimir Dolgikh, who was in Yerevan, described the rallies of hundreds of thousands as a “group of people,” which was perceived simply as an insult.

Postage stamps issued in 1988.

1.”Perestroika: The Continuation of the October Mission,” “The Acceleration of the Democratization of Openness (Glasnost).”

2. “Perestroika: Reliance on the Vital Creativity of the Masses.”

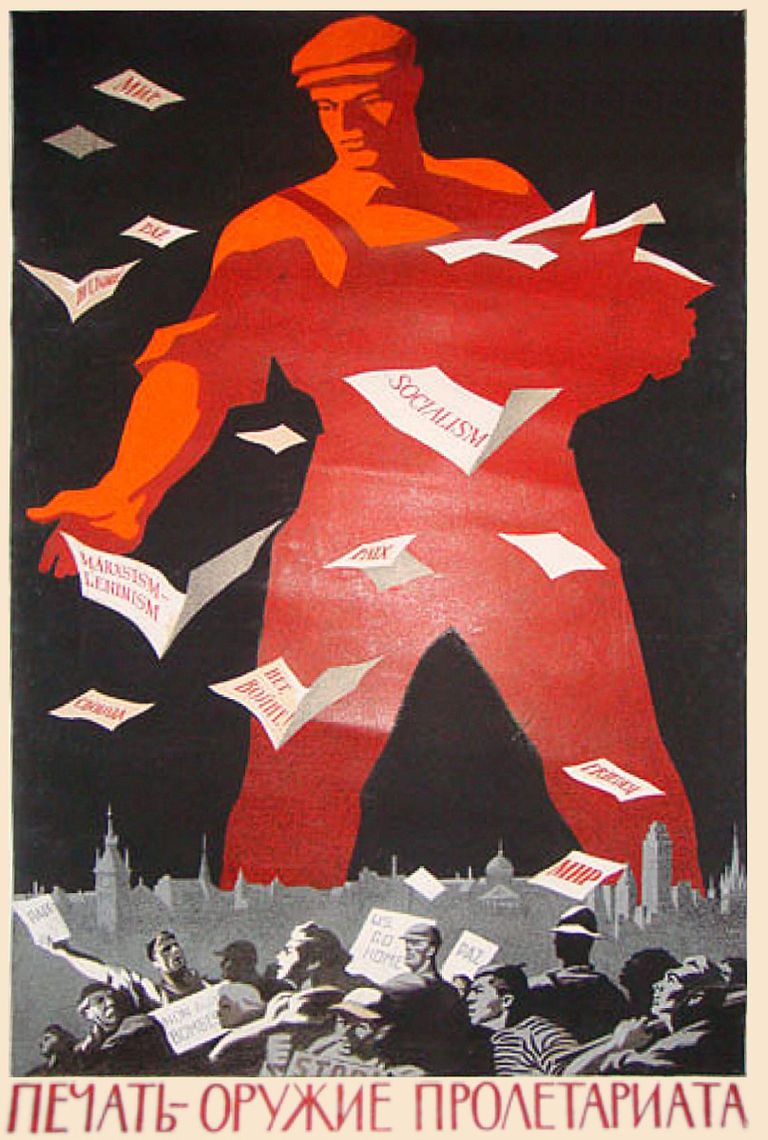

d) A variety and diversity of visual material (posters, signs, transparencies) was produced in large quantities (I have managed to archive about 1000 samples, which can be subcategorized into 20 groups) [5]. Such abundance of material is evidence of a high degree of pluralism in a deeply national movement and one that was not purely political in character, as for example, was the case in Baltic Republics. A researcher can see the emergence of a large group of people who are diverse, who increasingly subscribe to liberal ways of thinking and at the same time are unified in regards to principal issues.

As mentioned above, the Karabakh Movement was developing under the policy of Perestroika, Democratization and Glasnost adopted by the leadership of the USSR. In academic literature, these reforms are described as a “revolution from above.”[6] In general, as was characteristic to the Soviet system, whatever was initiated at the bottom would eventually have to be directed from above by the leadership of the country. Any divergence from this line, despite the activity and the constant urgent calls of the masses, would be considered a hindrance to the process of reformation/Perestroika. In this regard, from beginning to end, the Karabakh Movement was initiated from the bottom up. And for this reason, from its very first days, the Movement was subject to attacks by the supreme leadership of the USSR.

a) The bottom up direction of the Movement was manifested in different ways. Its most important characteristic from the outset was that it would be a peaceful struggle, adhering to the letter and spirit of the Constitution. If prior to the Movement, the Constitution was regarded as a useless piece of paper and the Supreme Council a place where deputies were occupied with superficial discussions and unanimously voted for bills authored from above, then during the Movement, people also gradually learned to appreciate the existing laws, the Supreme Council was considered a body that had to express the people’s will through its decisions and deputies were obliged, by mandate, to make that will be heard. Special groups called “Constitutional” were created to coordinate the work done with the deputies.