Photo by Roubina Margossian.

2016 was supposed to be dedicated to the smooth preparation for the 2017 parliamentary elections, which the Republican Party was confident of winning in the absence of any effective opposition. Instead, it was an unprecedented year full of crisis and upheavals in which both external and internal actors challenged Armenia’s equilibrium.

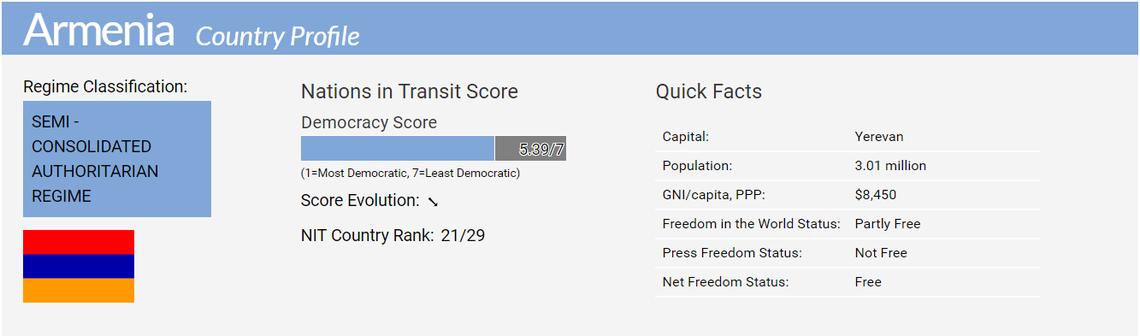

Armenia is considered a Semi-Consolidated Authoritarian Regime and is ranked 21 out of 29 former Communist countries on the democracy score. This according to Freedom House’s Nations in Transit 2017: The False Promise of Populism report that was released yesterday.

The report is an annual survey of democratic reform in the 29 former communist countries from Central Europe to Central Asia.

On the Democracy Score, a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 being the most democratic, and 7 the least, Armenia scored 5.39 out of 7. Last year’s score was 5.36.

According to the report, the following are the reasons for the score changes:

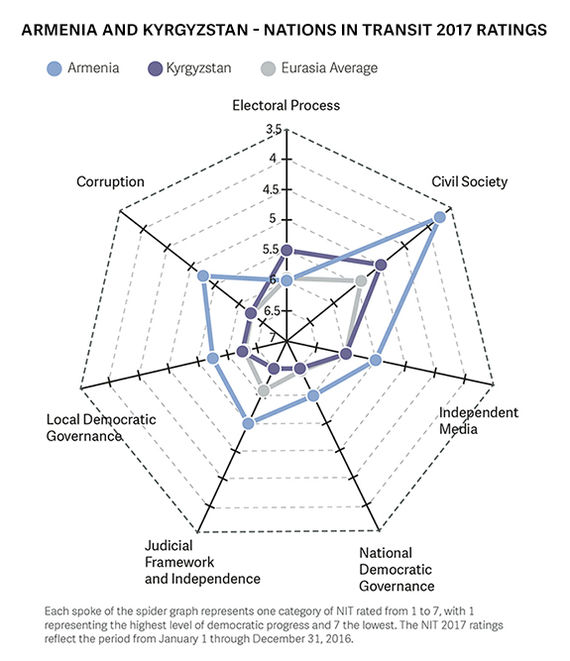

National Democratic Governance rating declined from 5.75 to 6.00 due to the inability of the government to address legitimate popular grievances before they spill over into protest, and then to resolve those protests without violence.

Electoral Process rating declined from 5.75 to 6.00 due to new evidence of serious shortcomings during the 2015 referendum and 2016 local elections, failure to resolve shortcomings in the law with new regulations, and adoption of experimental formal rules in the new electoral code.

Independent Media rating improved from 5.75 to 5.50 due to increased professionalism, diversity, and accessibility of internet media, which is challenging the dominance of television as the main source of information.

The report states that the past year was unprecedented for the crises and upheavals, “in which both external and internal actors challenged Armenia’s equilibrium.” These included the Four Day War in April 2016 and the Sasna Dzrer takeover of a police station in Yerevan a few months later that threw the country into chaos.

President Serzh Sargsyan, in an effort to divert attention from the inept handling of the protests by the country’s security forces, coupled with poor economic performance, made major shuffles to the government. After the resignation of Hovik Abrahamyan, Russian-Armenian businessman Karen Karapetyan was appointed prime minister. “The appointment of new faces to key positions, and their promises of rapid reform in the fields of economy and governance, as well as some initial actions, had an appeasing effect, at least in the short term,” the report states and goes on to say that these changes were a prelude to the parliamentary elections.

Despite the many setbacks the ruling Republican Party and Serzh Sargsyan confronted, they nonetheless remained the dominant political force in the country.

Read the whole report here.

The democracy scores and regime ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. The 2017 ratings reflect the period January 1 through December 31, 2016.

Armenia and Kyrgyzstan:

Changing Constitutions to Keep Things the Same

One benchmark for distinguishing between democratic and non-democratic systems is the ability of voters to change their leadership through elections.

In the last two years, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan have shifted from presidential to parliamentary systems in an attempt to make such political change harder to achieve.

Presidents Serzh Sargsyan of Armenia and Almazbek Atambayev of Kyrgyzstan argued that constitutional revisions were needed to bolster the democratic power of parliaments in a region where strongman syndrome is endemic. But the actual effect of the reforms will be to entrench the presidents’ parties and an oligarchic elite even further.

Armenia and Kyrgyzstan fall near the threshold for designation as a consolidated authoritarian regime in the Nations in Transit methodology, but each retains a measure of political pluralism that prevents total domination by one person or group. In both cases, the incumbent presidents are approaching the end of their terms and cannot run again. Moreover, they cannot be confident that fellow elites or the public would not revolt if they simply extended their terms, either legally or extralegally. The constitutional overhauls are seen as a way for Sargsyan and Atambayev to preserve their power (and assets) without risking an open confrontation.

Certainly both presidents pulled out all the stops to ensure the success of the constitutional referendums. In Armenia, after the oligarch and Prosperous Armenia Party leader Gagik Tsarukyan (better known by his nickname Dodi Gago) called on Sargsyan to resign, the president expelled him from the National Security Council and ordered an investigation of his business dealings. Tsarukyan backed off and withdrew from politics for over a year.

In Kyrgyzstan, the constitutional reform was not on the agenda at all in the fall 2015 general elections. The president raised it only several months later, after the parliament had already convened. When the governing coalition declined to take up Atambayev’s proposal in parliament in October 2016, Atambayev pulled strings to force the coalition’s collapse and install a more pliant alliance that supported the referendum.

And in both countries, the referendums themselves were held on short notice, with little debate and poor public understanding of the changes, and with intimidation and state patronage that ensured passage. In Armenia, a monitoring mission from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe noted that violations on the day of the referendum were so flagrant as to cause an “alteration of the actual voting results.”

So what did Atambayev and Sargsyan gain from the new constitutional arrangements?

In Armenia’s case, aside from the shift of powers to the parliament, the most significant provision of the revised constitution was a new system for ensuring a “stable majority” following elections. This procedure—designed for countries that have suffered from perennially unstable coalitions, which Armenia has not—grants extra seats to the party that wins a plurality in the general elections, strengthening its hand in government formation. The result in Armenia will be a government and parliament dominated by Sargsyan’s Republican Party of Armenia (RPA), which Sargsyan can continue to lead either officially or from behind the scenes; he has been ambiguous about whether he would serve as prime minister. The parliamentary system is simply a mechanism for ensuring that the RPA will remain in power for the foreseeable future, despite the country’s increasingly frequent outbreaks of antigovernment protest.

In Kyrgyzstan, the constitutional changes were more of a deal among a number of groups in the elite, most importantly President Atambayev and his Social Democratic Party of Kyrgyzstan (SDPK). The revisions actually do not weaken the presidency much at all: what they do is reduce the independence of the judiciary and increase the control of the prime minister over the governmental coalition. It will be much more difficult for dissenting factions within the ruling coalition to break away, and the prime minister will enjoy greater control over local governments, at the expense of local elected officials. The changes will effectively bolster the position of an oligarchic ruling class with little popularity or legitimacy.

The Armenian and Kyrgyzstani cases illustrate how authoritarianism continues to evolve and adapt to changing circumstances, even in weaker states with superficially competitive political environments. Faced with large-scale popular discontent and lacking the resources to completely co-opt or repress civil society and the opposition, presidents and ruling parties in these countries must find more subtle ways of retaining their grip on power. They may be changing the very structure of the state, but the goal is to preserve the political status quo.