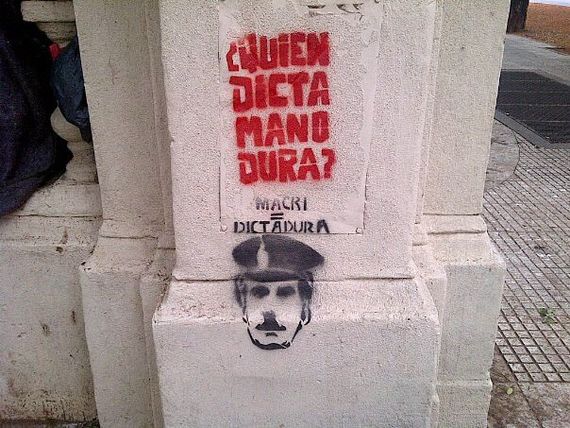

“Ghosts of the past.” Graffiti in Buenos Aires. Photo by the author.

“ The old man’s newly lit cigar was resting on the edge of the copper ashtray; the gentle, orange glow from the tip of the cigar was seeping through the young ash. ”

It was midsummer and the glistening rays of the sun had penetrated the crevices of the melancholy city. The native fair winds had abandoned the urban landscape in search of more glamorous shores across the Rio de la Plata. As it was always the case in these parts, the dreary calm was deceiving; there was always much more to the intricate city than was visible to the untrained eye. The old man had been sitting at Café 36 Billares for over an hour on the storied sidewalk of Avenida de Mayo that lead to the Plaza del Congreso in Buenos Aires. His favorite yellow and red box of Swiss Villiger Grossformat Export cigars laid flat on the wooden table next to the untouched cup of café con crema*. A box of matches sat on top the Villigers, partly covering the clean lines of the Swiss design. A small glass of sparkling water accompanied the coffee cup; the clear liquid was still fizzing. A paperback print of Jorge Luis Borges’ Ficciones in Spanish, opened to page fifty-four, was laying face down on the table. The old man’s newly lit cigar was resting on the edge of the copper ashtray; the gentle, orange glow from the tip of the cigar was seeping through the young ash. As the old man’s thoughts started to wander once again to the days gone by, he picked up the unusually square-wrapped cigar and took a deep puff. He released the smoke from his chapped lips into the warm summer air, rendering imperfectly animated white rings.

The old man had spent some of the best times of his life in the melancholy city whose best days seemed to be well behind her. By being in the city where he had experienced his better days, he had successfully tricked his brain to reproduce the same feel-good juices of yesteryear. Nostalgia was something he had willingly embraced. He was not very different from the city where he had chosen to spend his last days. He had lived a life of excess and careless disregard for his health. He knew better than anyone that his vices had finally caught up with him, but he had few regrets. And although his face still flaunted an effervescent charm, he was deteriorating inside, just like his adopted hometown.

Four well-dressed porteños* were sitting at the table next to the old man, two women and two men in their late thirties. They didn’t seem to be couples, just old friends. Two of his neighbors, a woman and a man, were engaged in a heated conversation. From their demeanor and clothing, the old man had deduced that they were either lawyers, doctors or architects. They were stylish, yet unpretentious in their choice of wardrobe. The exchange continued back and forth between the man with the smart, silver framed reading glasses and the women with auburn eyes. The man’s sky blue eyes were piercing, yet kind. The woman’s wavy, long brown hair reflected a hue of chestnut. Her makeup up was minimal; the dark eyeliner framed her mystic eyes. Maybe she had a strain of gypsy roots from the Balkans, or she was a descendent of a Neapolitan family, or, she was the granddaughter of some immigrants from Asia Minor, the old man imagined. Guessing people’s origins was one of his favorite pastimes.

“This country is going to shit!” The woman said.

“It sure is.” The man with the smart-looking glasses agreed. He was sitting across from his friend.

“First the dictadura*, then the economic collapse and now these pseudo-leftist demagogues trying to manipulate the poor to stay in power.” The woman added.

“Well maybe the milicos* weren’t so bad after all.” The man with the smart looking glasses whispered unconvincingly. He was well aware that his insensitive remark would get a rise out of his beautiful, spirited friend.

“Yeah, sure! You, out of all people, you, Mateo?! How can you say that?! I know you. If your were a young man back then, you would have either been a naive Montonero* recruit leading the fight against the milicos trying to spark a world socialist revolution, or being fed to the pigs, depending on where you were in your revolutionary career!” The woman did not hold back.

“Hmmm… I am no revolutionary Micaela, but I guess it’s much more progressive being killed by a bunch of teenagers on paco* than the milicos.” Mateo fired back.

“Less heroic, for sure!” Micaela agreed reluctantly. “And why does it always have to be a choice between the milicos and this shit? Don’t we deserve better?” She argued.

“Well, maybe this is all that the we deserve. Have you ever thought about that?” Mateo asked rhetorically as he adjusted his reading glasses on his boney nose.

“You are an idiot! Have you ever thought about that, eh?!” Micaela replied.

“Hahahaa!” Mateo burst into laughter. “I love you!”

“You are a shithead! And maybe, I love you too!” Micaela said. An affectionate smile appeared on her flawless face; her high cheekbones blushed.

The old man was secretly enjoying the banter among friends. He couldn’t focus on the Ficciones. He had read the book in English when he was much younger but even then, when his brain had more living cells, he wasn’t able to comprehend everything. He had thought that at second attempt in Spanish, he would have better luck, but his neighbors’ conversation was more entertaining.

As the old man was about to reach for his cigar once again, he noticed a boy approaching him on the sidewalk. He had gotten used to being alert on the streets of Buenos Aires. He was always aware of his surroundings and kept an eye out for petty street thieves, a sign of a true porteño. He took a quick look at the boy and gathered that he must have been no older than nine years old. His red shorts were worn out and complemented by a replica Independiente jersey, a soccer club from the Avellaneda district of Buenos Aires. His soccer shoes seemed to have been well used but in good enough shape to protect his feet from the sidewalk. His pitch-dark, thick, long hair glistened in the afternoon sun. He had a determined look on his tanned face.

The old man immediately retreated into a defensive mode.

“Hello sir. Would you like…”

As the boy started to speak, the old man waived his hand in the international gesture of “Go away!” and picked up his book.

“But, sir…” the boy insisted.

The old man was now determined to display a sterner attitude toward the kid; he raised his right hand and flashed his index finger, moving it from the left to right, right to left. “No way!” was his implied response.

To reinforce his unyielding position, he dropped his eyes to the wooden, brown table and picked up his café con crema with his left hand; he took a sip while avoiding eye contact with the boy.

The boy finally got the message.

Besides, the boy only had a few more hours left in his workday before sunset. After finishing his shift, he still needed to catch a couple of bus routes to get back home. He wasn’t about to invest too much time in the cranky old man. As the boy turned his attention to the next table where Mateo and Micaela were sitting, a middle-aged waiter stepped out of the cafe.

“Don’t bother the customers. C’mon, get going!” the waiter shouted at the boy.

The old man felt vindicated. Not only had the waiter identified the boy as a nuisance but his enlightened neighbors had also ignored the young street merchant. It wasn’t that he didn’t care about the less fortunate, but seeing so much misery on the streets of the city, he had become immune to the plight of the poor. He justified his lack of compassion by the fact that he felt helpless in making a real difference. He had made peace with being jaded at a point of no apparent return.