Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

The photograph opening this article represents the Meghri airport in the 1980s, and is taken from the Facebook group of Meghri natives (Meghrians). Under each photograph we find the memories of the natives of Syunik about the city and themselves – about the past that spreads beyond the borders of the photographic image.

Meghri’s airport is a building of the late Soviet period, the construction of which in the 1970s presented great challenges, even before it began; the complex mountainous terrain did not allow a plot of flat land on which the runway could be built. When the airport was finally completed in 1985, it marked a victory for Armenian builders and officials over nature and, to a lesser extent, the bureaucratic mechanism of Soviet power. Nevertheless, the airport’s lifespan was less than the time it took to build it. It stopped operating during the dark years of the Soviet Union’s collapse and the outbreak of the First Karabakh War. The trajectory of the Meghri Airport was but a brief moment – located in-between the lightning-fast decline of the Soviet present and the future independent state of Armenia. It was sunk into darkness, just like celluloid film is sunk, in order to later be developed and become a carrier for some fragment of the irreversibly lost past. Most of these things, which lie outside of the photographic frame, are quickly forgotten. What remains in memory is what the locals experienced in their personal realm

“The ticket [to Yerevan] was 25 rubles. You could get to the capital city in 25 minutes. True it was like an araba[1],” remembers one of the locals, commenting under the photograph on the Facebook page.

Another commentator corrects him.

“The helicopter would reach Yerevan in an hour or an hour and ten minutes.”[2]

The Meghri Airport, 1985.

Some members of the group remember the failures of the late-Soviet technological achievements.

“For security, they had put a latch on the door from the inside so that it would not suddenly open mid-air. And after landing, the Kukuruznik [Antonov An-2 aircraft] was chained to a special ground fixture, so that the wind would not blow it away. It is a windy place.”

At the Meghri airport.

The fact that the photos depict a past that has been sharply disconnected from the present, is made apparent not only by the monochrome look of the images, but also the lengthy commentaries about the pictured aircraft’s technical specifications or the cost of the ticket in Soviet rubles. The photo becomes a kind-of Bickford fuse that detonates countless memories, and brings up from this wreckage, the common layer of memory, the vein of collective memory – the memory of Place, of Meghri.

“I went to Yerevan with the last helicopter. After that, there were no other flights to come back with….” and the chain of comments below the photograph ends, to give place to other photos and other chains of memory.

The Facebook group “Old Meghri and the Meghrians” contains hundreds of carefully collected and scanned old photographs. The page was created in 2014 by Pap Ohanyan from Meghri. In seven years, ‘Old Meghri’s’ archive has been regularly updated with photographs and documentary materials. It currently features over 1500 historical images. There are 3400 users in the group – approximately the size of Meghri’s population today. Although the group is open, there are almost no non-Meghri natives there, according to the group’s founder. It is more active than the official pages of many institutions, but at the same time it is also isolated, living a separate life, disconnected from the rest of the digital world. Nestled in the far south of the country, Meghri exists in almost the same way.

Time and place; this is what one involuntarily begins to think about while examining the photograph of the plane. Each picture uploaded in the group seems to be a magical portal into a novelistic space-time, which takes the viewer from the documentary context into the world of the imagination.

No planes have been seen in Meghri for several decades; the railway is also non-functional, and the pitiful fragments of the rails laid down during Soviet times seem to be in silent mourning… The route from Yerevan to Meghri is a long winding ribbon with narrow mountain roads and deep gorges. The traveller, who has been forced to cross the whole of Armenia to get here, will think that it is the end point of the country. But such a description is unacceptable for Meghrians: “Meghri is the beginning of our country, definitely not the end.” “Meghri is our southern gate,” was the saying in the Soviet era, when the city was the furthermost point of the Republic of Armenia, but somehow, it seemed like it was standing on the edge of the entire Soviet empire. Meghrians were oppressed by the feeling of being on the outskirts of a state or an empire, and they were endlessly trying to change and revise their own destiny with surprising optimism.

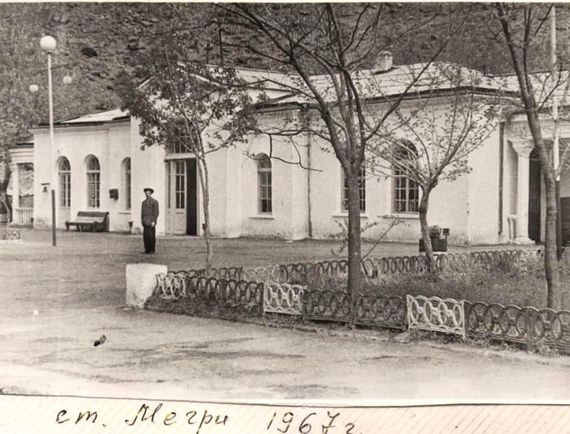

The Meghri railway station, 1967.

Since independence, few communities in Armenia have treated what researchers call local identity with such care and concern. It is an identity entrenched in local myths, the dialect, in urban architecture and everyday culture, and, of course, in attempts to portray one’s own life. Being geographically far from the capital, bordering on other cultures and other states, Meghrians have developed this sensitivity toward their own city and its past for decades, if not hundreds of years.

The users of the Facebook page remember the different corners and sights of the city, their locations, and the paths leading up to them. One describes the area, another writes about oblivion, a third stops seeing an architectural image and simply begins to narrativize their own nostalgia for the past. The photographs that have been collected in the group turn into a unique virtual version of a provincial museum, or rather, a non-museum, because the active participation of the community destroys the atmosphere of a traditional museum.

Pap Ohanyan, recollects how years ago he began to notice that the appearance of the Pokr Tagh district where he lives, is gradually changing due to new construction and the absence of architectural heritage preservation. People leave, and the youth forget how the city used to live. The “dark and cold years” of the early 1990s, the waves of emigration have continuously desolated and still continue to desolate Meghri and its surrounding villages, just like other regions of the country. In this sense, the Facebook photo group is a unique attempt, not to stop history, but to start reflecting on the changing reality, be it architecture, geography, culture or everyday life.

“In the past, the village of Agarak was not far from here. It has almost completely disappeared. There is only a small church left. There are no inhabitants. I found and published the photos of that village, and users started to remember all the things they knew about the former residents of the village. It seems that, apart from those photos and memories of the place, nothing has been preserved,” says Pap Ohanyan.

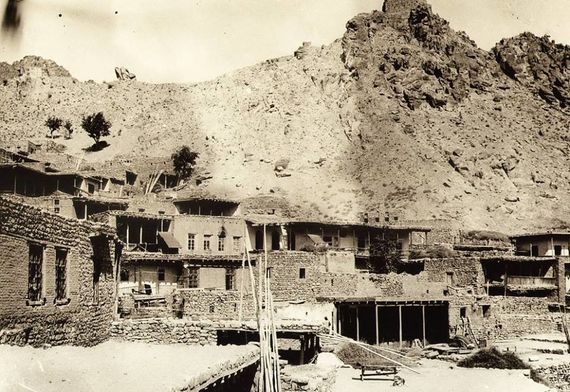

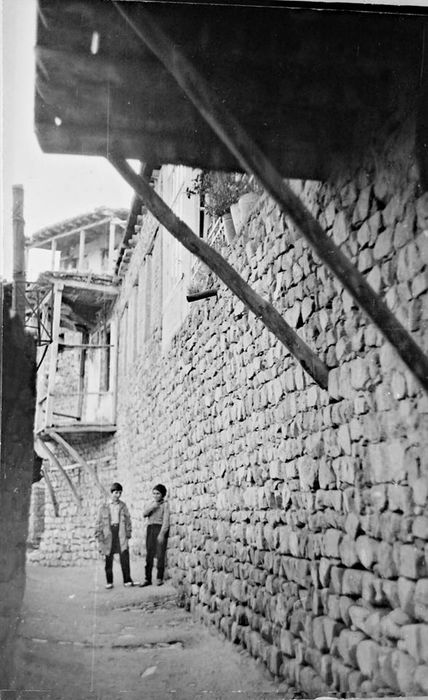

Medz Tagh, Meghri.

The community center at the Agarak village, 1947.

Grandma Arus and grandfather Bakhshi, Lijk village, 1982.

Pap Ohanyan with is mother, Meghri, 1970.

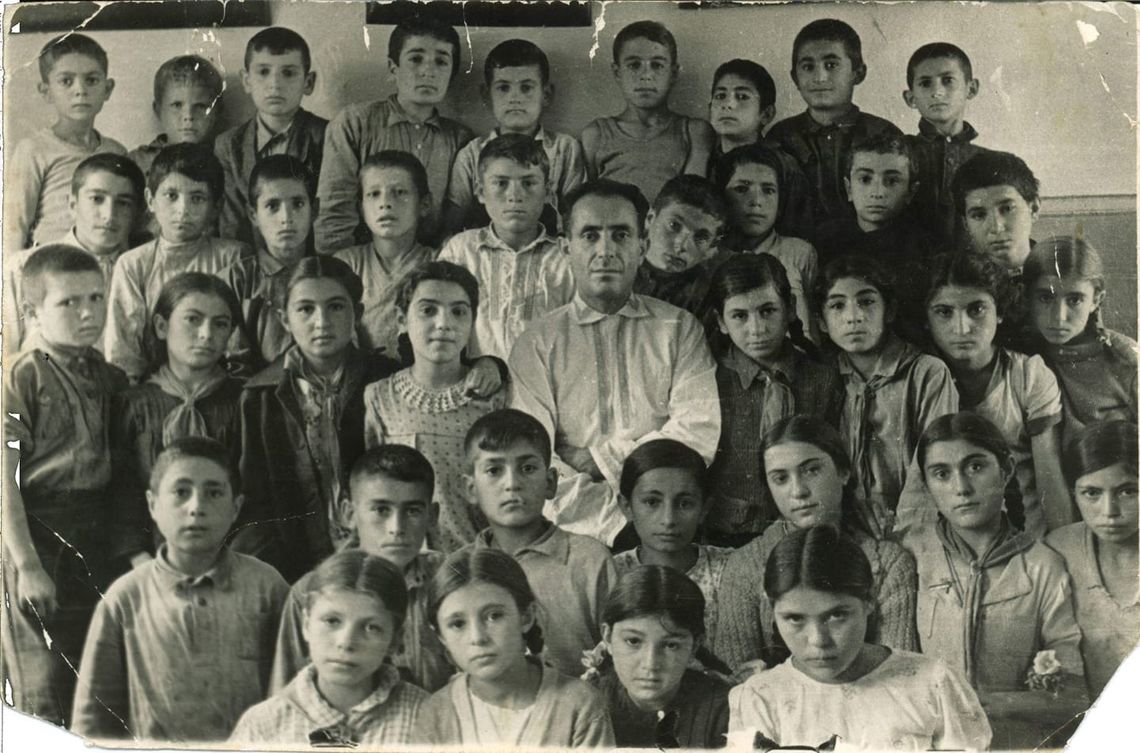

The photographs, which depict the architecture and the life of Meghrians, become an anthropological and ethnographic method of documenting the past that is unique in its veracity — an unusual mode of community “self-study”. In this big online photo gallery of Meghri one can see separate albums dedicated to different villages and settlements (Shvanidzor, Tashtun, Gudenis, Lichk, etc.). The photos are also grouped according to professional occupations: fragments of the city’s industrial past (Wine Factory, Gravel Factory, Meghri Canning Factory), local educational and cultural institutes (Meghri State Theater, Russian schools in the Meghri region, etc.). Space is extended and condensed via photo-documentation, exclusively through the use of unofficial local history channels and personal archives.

Photographs of local architecture and urban landscape testify an unbroken connection with the past, but simultaneously show that Meghri, like many other post-Soviet cities, began to experience a cultural decline as soon as architecture lost its functional and aesthetic significance. The official photographs of the 1960s and 1970s demonstrate the achievements of the mining industry, technical advances and the cultural life of the center that had reached the “periphery” — glorifying the victory of the Soviet state. But Meghri’s foundational, vernacular life and architecture, which have been preserved here for centuries, are transmitted through unofficial, vernacular photography.

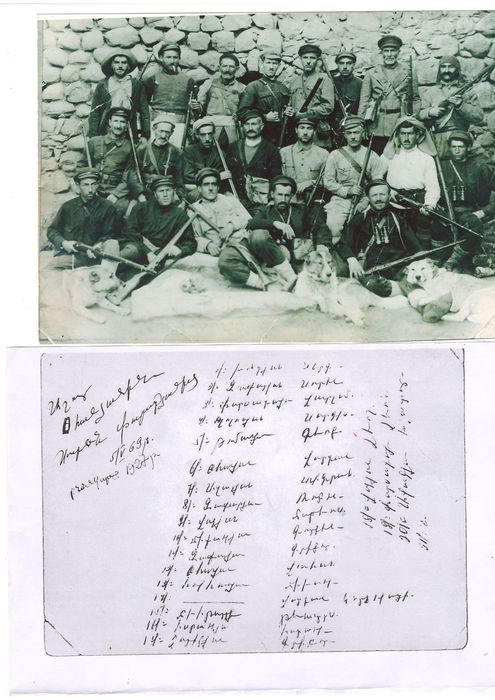

Meghrians, 1927.

Pokr Tagh, Meghri.

Meghri, 1965.

Meghri, 1950s.

Meghri, 1960s.

Theorists of photography often state that the photograph has managed to overcome the role of being exclusively a form of documentation and has achieved autonomy in the field of artistic photography. For that reason, a photograph should not be considered merely as an illustration of a text, a visual interpretation, but must be perceived through its potential to equal narrative or literary devices. For the average viewer, such tightrope walking can be problematic; they would have difficulty in keeping this formula of equality in mind, as the illustrative role of the image has been prevalent in our culture for too long. But in this instance, the Meghrians’ group unexpectedly manages to break that stereotype; here the primacy always belongs to the photograph, while the text is drawn around it and comes after it. In this process, the photograph gradually begins to dissolve and disappear, letting memory shine through vividly and clearly, and with each new recollection the photographic image becomes more and more transparent.

Yet, it would be unfair to talk only about the dissolution of the photograph in the articulations of familial memories; sometimes user comments express the despair that comes with oblivion, too. Meghrians do not always manage to find out what or who exactly is depicted in the photograph; they excitedly begin commenting, trying to recall, but those attempts can sometimes be futile. And when the photograph refuses to expose itself and give way to memory, it becomes memory itself. Living on the border of different cultures, states and civilizations, Meghrians sharply feel these edges that are created and erased by the photograph — the borders between the present and the past, between the ruins and the active vital energy.

The interactivity of this photo-based group is manifested not only in the fact that each photograph invites users to participate via their comments. The creator of the virtual community talks about the process of collecting and digitizing the photographs, and how those Meghrians who do not have the opportunity to scan the image, personally bring their old photos, handing over the miniatures of their own past to the whirlpool of the city’s collective past. It seems that no official institution dealing with the visualization of local history could ever achieve such a level of trust. Once again, we have to admit that the secret of the success of the virtual group lies in the fact that it was formed by ordinary residents; it is nothing if not an act of the Meghrians’ vernacular life.

In the century before last, photography was a means to conquer new territories and to map them out. It allowed one to vicariously travel around the world, across borders, getting to know and differentiate between diverse places and the people who inhabit them. But today, apparently, a somewhat different type of photographic journey takes place in the digital space. Photos, such as those published in the Meghrians’ group, also create the illusion of travel, but now they serve as a means of transportation within specific geographical and temporal boundaries, especially since the latter are at risk of becoming inaccessible at any time due to wars, pandemics, environmental and other disasters.

Time suddenly stopped the planes and trains that could take us to Meghri in a matter of hours. Overcoming time and space, the photographs of old Meghri — reborn in digital reality — became one of the few means of getting there. The hundreds of photos collected in the fuselage of the memory plane, set in motion all that has calcified over time. What history had no control over suddenly became possible for the memory, which outlines the real and mental map of the city through old photographs.

———————–

[1] An old Persian word for a two- or four-wheeled cart that was common in the South Caucasus in the 19th century.

[2] Remote airports in Armenia and other Soviet republics were usually serviced with helicopters and light planes.