Outside frameworks of chronology and geopolitics, a small structure stands high on a high hill. Its architecture resembles a plucked bird, but inside the building, everything shines immaculately. Several times a day, the cleaning lady walks around with a bucket in hand, ensuring that not one speck of dust settles on the new white floor tiles. A group of other people also comes to work: Eric Grigorich, who holds a high position there only because his Lada Niva is parked right at the entrance of the structure, his secretary, dispatchers, a doctor, as well as other men and women who, sitting in their rooms, play backgammon and chess, solve crosswords, make coffee and dough, listen to music and discuss politics. The structure is, in fact, an airport that’s missing a few important details: the hustle and bustle of travel and planes.

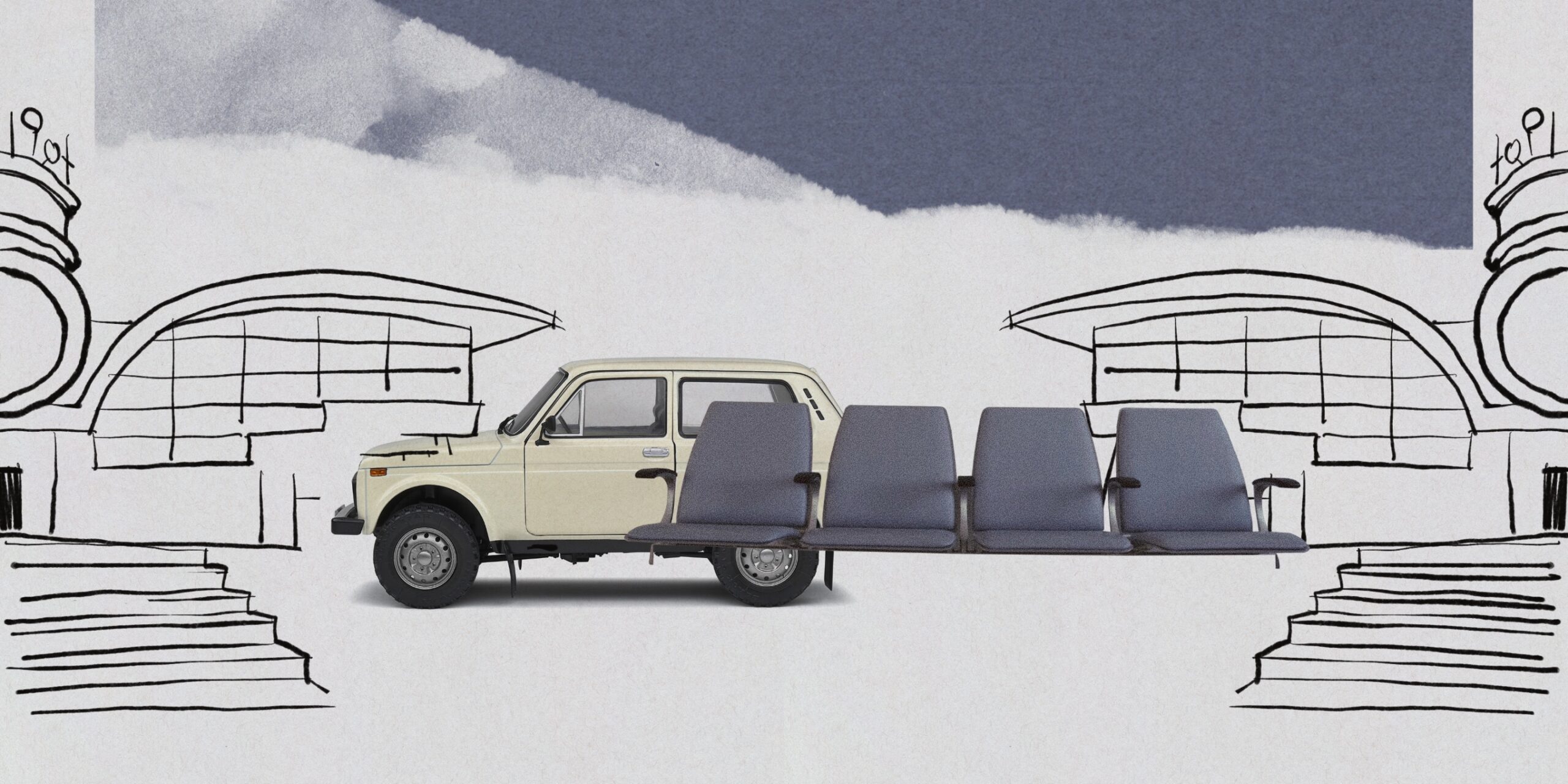

Director Garegin Papoyan’s film “Bon Voyage” (2020) is about Stepanakert’s airport. This is now the second full-length film about the facility. Built in 1974, the airport ceased operations after the First Karabakh War in the 1990s and was scheduled to reopen in 2011 after a major renovation. However, due to the unrecognized status of the Artsakh (Nagorno Karabagh) republic , it has not been put into operation. French-Armenian director Nora Martirosyan told a story about Artsakh, a republic that cannot speak or fly, and Garegin Papoyan tried to tell the story of the airport through the staged-documentary form, a prism that begins to metamorphosize during the film, becoming thin and transparent, revealing the presence of the director and his camera.

In “Bon Voyage” there are no main characters around whom the film would revolve––the airport is the star. The people working inside are the airport’s engine, its integral part. They also propel the film forward and it is through this movement that the story unfolds. We get to know them as they arrive at the airport in a broken and worn-out minivan, then we go to their rooms, and see how they operate. We understand from their words and behavior that they are aware of the camera’s presence in the room and have not gotten used to it, that they are playing their own parts according to an idea they have of themselves. At first, it feels artificial and a bit contrived, but the director soon erases this impression. The characters begin to confront the camera, discuss its presence, and complain about it. Those participants who “understand the importance of the film” begin to explain and convince others to be a part of it, claiming that the film will only further serve their objective (to open up the airport). In the end, everyone agrees to play the “working airport” game – a training drill in essence – which ultimately provokes a fascinating entanglement between documentary and fiction, dreams and reality.

“Bon Voyage” has a unique sense of humor, unstaged and unrehearsed, sometimes witty, sometimes absurd. A rebellious secretary complains that she’s been filmed more in the past few days than a Hollywood star and refuses to appear on screen anymore. Another employee visits the doctor to explain that she feels nauseous, but “deep down” in her soul. During a meeting with staff, when airport director Eric Grigorich talks about the film crew and the need to help them, a few start to dissent, not wanting to give an “interview”. Grigorich calms them saying that this is “not an interview, but a conversation and that they just need to talk.” These scenes become a key feature of the film, not only because they disrupt the airport’s sterile atmosphere, but also show the skill of the filmmaker, who manages not to cross the delicate line between humor and mockery. The camera does not caricaturize these people or their thoughts and words.

Music plays a significant role in the film. For the main soundtrack, the film uses music created by one of the staff working at the airport who sits at his computer. This constantly cut up, seemingly dysfunctional music is irritating and very similar to the failed attempts of getting flights out of the airport. The music in other parts of the film is also what the employees listen to when killing time. They’re mainly Russian chanson songs from the 1990s, through which the director helps us understand the characters of the film and their preferences, and the time period in which these people still inhabit mentally.

The work of the cinematographer deserves particular attention: Artashes Matevosyan manages to create a special harmony between shots taken from unexpected, off-kilter angles and Artsakh’s natural landscape. The focus is not on inspiring images of the highlands, but on dry and frozen fields, which further emphasizes the introspective quality of the film. In some scenes, impressions of crooked mirrors are also present, further highlighting the distorted reality depicted in the film. This aesthetic and evocative approach of a somewhat alienated viewpoint is typical of the Armenian documentary genre of recent years, but here, it is presented in a more refined and polished style—a significant achievement for a first full-length film by a young director.

The film is a bundle of big and small metaphors. In addition to the ambivalent use of music in most scenes, the director introduces us to the hardships and the farce the characters of the film live in, from the taxi cab that couldn’t get its engine running to the lightweight plane whose flight over Stepanakert suddenly accrues an immeasurably weighty symbolic significance. The biggest metaphor is the Stepanakert Airport itself, which symbolizes the ‘paralyzed’ or frozen status of the Republic of Artsakh. This small structure, which was never able to operate international flights due to geopolitical realities of the region, is similar to the Republic of Artsakh that has been developing infrastructure and trying to build a state that is not recognized by anyone. Meanwhile, for thirty years, Armeniansl believed that our Godot would come, that Artsakh would receive its status and fly. Contrary to Nora Martirosyan’s film “When the Wind Calms Down,” which is imbued with a breath of poetic optimism, Garegin Papoyan’s film threads on a more realistic ground, rather than a pessimistic, absurd or illogical one.

In “Bon Voyage,” Garegin Papoyan manages to recreate a ‘real’ Kafkaesque world in the form of the Stepanakert Airport, where people follow a seemingly unreasonable system, and continue to do their work with incredible persistence, without questioning its meaning. It’s possible that they are still waiting for their Godot, known for his habit of never arriving. Maybe their motivation to work is economic: they are paid, they are provided for, and the rest is secondary. On the other hand, the film’s aim is not to find out why these people work or what they believe. The film is about the daily absurdity and illogical reality of living according to grand political and national agendas, in which perhaps we are all immersed. It is precisely those circumstances that make this film “fly” beyond the scope of a small local story, making it universally understandable and relevant.

Et Cetera

Film reviews

Waiting for Spring…

In this review of the film “It Is Spring” dedicated to the Artsakh conflict, Sona Karapoghosyan writes that cinema should be a tool for critically revealing and interpreting the world, and not a bandage to hide our collective complexes and fears.

Read moreThe Cinema Screen: A Political Battlefield

Mher Mkrtchyan has made a marked and oppositional political film, which, however, is too superficial and collapses under the incredible transparency of its agenda, writes film critic Sona Karapoghosyan.

Read moreDid the Wind Drop? Nora Martirosyan’s Optimistic Drama From Artsakh

Director Nora Martirosyan’s film “Should the Wind Drop” reveals the frustrating situation surrounding the airport as a starting point to delve into the history, problems and spirit of Artsakh.

Read more“Where Are You, Soghomon?” Arman Nshanian’s Melodrama About Komitas

“Songs of Solomon” promises to tell the story of young Komitas but ends up disappointing as the direction drastically changes, turning into another tragic film about the Armenian Genocide and Komitas simply a faded symbol emphasizing a lost culture and history.

Read more