Introduction

In 1894, under pressure to settle a divorce case, a member of the Ottoman Armenian National Assembly’s Religious Council stated in frustration: “For God’s sake, let this divorce be put off until the next election of the Council. Let this not happen while we are serving as Council members.”[1] This reluctance had its roots in a number of factors, including the absence of a comprehensive marriage law, the inability of Armenian authorities to reinforce legal decisions, and the ever-changing cultural values that legal approaches failed to address. This article examines the state of marriage law and culture among Ottoman Armenians. It illustrates the complex and entangled power relations involved in reforming the institution of marriage, and analyzes the multilayered struggle of Armenian feminists to bring change to the Armenian family and marriage culture.

The State of Marriage Culture and Law

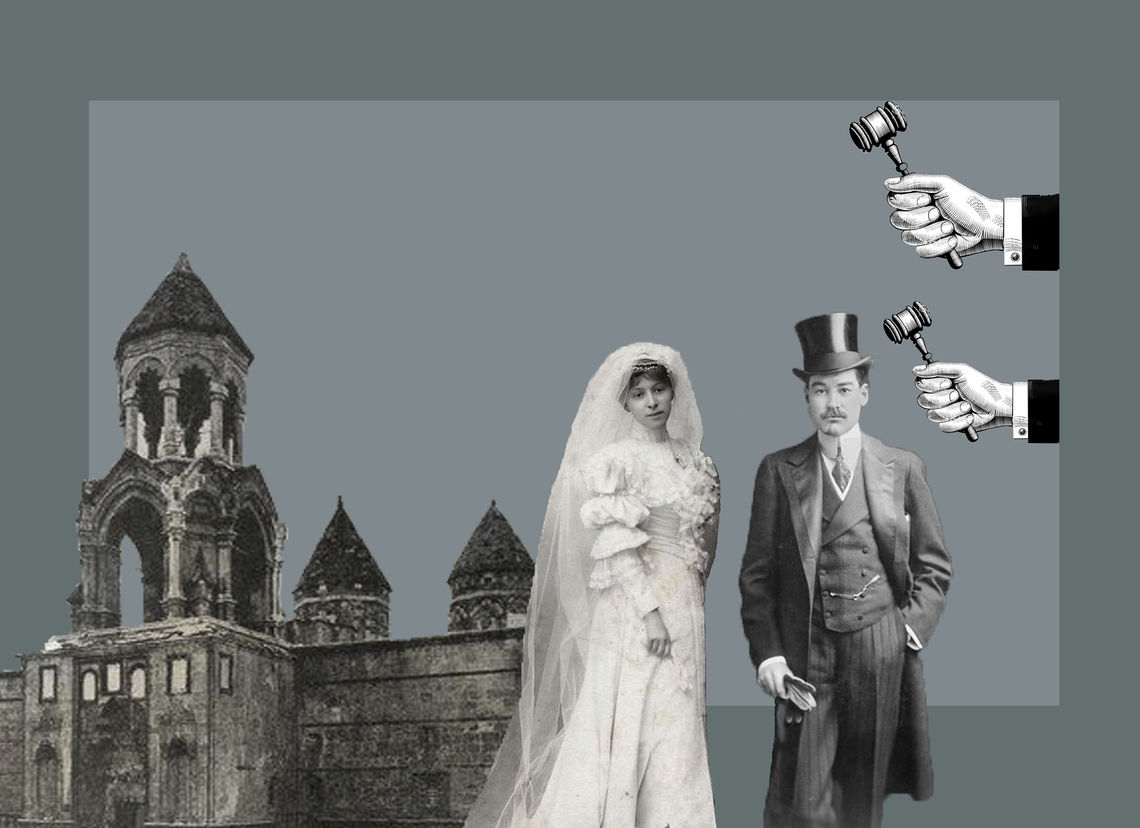

In the period under scrutiny, marriage among the Ottoman Armenians was a religious act, carried out and registered by the local church. Arranged/forced marriages were common practice. Marriage was regarded as a contractual relation between two families, rather than the marrying couple. The common belief during this period, both among religions and secular authorities as well as reformers, was that the family had deteriorated because of marriage “vices” and, therefore, a struggle was launched by these parties at the legal and discursive levels to stop the “microbes deteriorating our nation.”[2]

Among the vices to fight against was child or early marriage. The most criticized age-related practice was beşik kertme, an agreement between the families of infants to have their children marry when they reached puberty. Despite the prohibition of this practice in 1811, cases of beşik kertme were reported as late as 1906.[3]

Dowry was considered yet another vice by the authorities and reformers. Its practice differed between cities and rural areas. In rural areas the groom’s family had to pay the bride’s family what was called başlık (head price), whereas in cities the bride was supposed to bring with her a drahoma (dramozhit or dowry in cash). Başlık and drahoma were considered to be the reasons behind the decline in marriage rate, particularly among the socially more vulnerable families.[4]

Religious conversions, as well as appeals to Muslim courts for a more rapid solution to divorce cases were of great concern to the Armenian religious and secular authorities. Conversions occurred for the sake of getting a safer and more desirable solution for the case filed. Instances were reported where a couple would convert to Greek Orthodoxy, and then re-convert to the Armenian Church upon the settlement of the dispute.[5]

Polygamy was perhaps perceived as the most alarming “unchristian vice.” Such cases were repeatedly reported in the provinces. It appears that the Religious Council was particularly zealous in stopping polygamy and less so for other phenomena, such as child marriage, forced marriage, dowry, etc.[6]

The goals set for stopping these family and marriage “vices” were clear to all parties. What was not clear, however, was who had a say in this reform.

Whose Reform?

The Constitution of 1863 of the Ottoman Armenians intended to secularize national institutions. However, instead of a shift in power relations, it had brought about chaos especially in matters concerning the family and marriage. Due to the composition of the Ottoman State, the Armenian community (millet), similar to the Greek and Jewish communities, was headed by the religious leader, the Patriarch. As long as the Ottoman State recognized the Armenian Patriarch as the only leader of the community, secularism among Armenians internally had its limitations. The National Assembly’s Judicial Committee, which handled family and marriage disputes, bore a dual character; it consisted of eight members, four religious and four secular. It was the duty of the Judicial Committee “to resolve family disputes and examine and solve trials passed to the Patriarchate by the Sublime Porte…”[7] Under the Constitution, if the Judicial Committee found a case “beyond its comprehension,” it was to pass the case to the Religious, Civil or Mixed Councils. If appeal was filed against any of the verdicts of the Judicial Committee, the issue was to be reheard by any of the three above-mentioned Councils too.[8] Thus, under the Constitution alone, family trials could be handled by practically any authority of the Armenian millet (religious, secular or semi-religious/semi-secular). Cases could also be heard at the Ottoman Muslim courts, as Christians were free to appeal to these courts. Moreover, what seemed like a simple divorce case could extend beyond the borders of the Ottoman Empire. Given the subordination of the Patriarch of Ottoman Armenians to the Armenian Catholicos at the Holy See of Echmiatsin (the Mother Church) in Russian Armenia, marital disputes of Ottoman Armenians were often referred by the Patriarch to the Catholicos when the former either failed or was unwilling to take responsibility for the case.[9]

Although national institutions bore a semi-secular and semi-religious character, the reform was increasingly discussed and understood in the language of secularization and the Church was often blamed for persistent ignorance and slow progress. Within the millet, there was a deep division upon a simple question: “Is marriage a private or public institution?” The religious authorities continued viewing “private” and “religious” as synonymous, and insisted that marriage was a private matter. The “public” and “secular,” on the other hand, were synonymous for the secular authorities, who strove to secularize the institution by opening the contemporary family and marriage phenomena to “public” debate.[10] The secular authorities also pushed for the development of a unifying legal framework.

Negotiating a “New” Family and Marriage Culture

While secular authorities struggled to gain power in the National Assembly with their efforts to secularize marriage, the reformers supported them through a discursive campaign launched in the periodical press and fictional literature. This campaign aimed to endorse a new family structure and marriage culture, and women were central to this discourse. They were singled out as the biggest victims of marriage vices, and their plight was spoken of with concern:

It is impossible to deny that recently family and love dramas have increased in Armenian society. And its is particularly young women who, at the cost of their own blood, come from time to time to show in front of the eyes of an indifferent society the hidden sufferings and concealed wounds. We pass by them every day but we have neither the heart nor the time to deal with them.[11]

Women in rural areas were reported to be particularly oppressed and more in need of protection. Since they lived in multiple and extended families, first they were subjected to the will of their husbands, and, after his death, to their sons and brothers-in-law. Of particular concern was the fate of wives whose husbands had migrated, leaving the family with no support or information about their whereabouts. The abandoned women were considered “a wound on the body of the nation.”[12] As much as divorce cases were subject to different arguments in other situations, “it is impossible to have two different opinions [in cases of abandoned wives]. It is necessary to support divorce.”[13]

Although the reformers used women’s plight to argue for improvement, they also held women responsible for declining mores. Upper class women were expected to serve as models of motherhood and wifehood to their sisters of lower classes. Keeping wet-nurses was highly criticized as an imitation from Europe and a “bitter fashion.”[14] Başlık (bride price) was believed to persist because women “are quite demanding.”[15] Although it was generally believed that the marriage rate was in decline because of young, educated and westernized men who thought of marriage as a burden, the upper class single women were criticized for scaring off men with their love for luxuries.[16]

On the other hand, when the structure and essence of a “modern” companionate marriage and “modern” Armenian family were discussed and championed, women were expected to serve as markers of change and were accused of hampering improvement with their “backward” ways. It was through the abandonment of old prejudices and alien traditions, and the embracing of moderate new norms that marriage could be improved and the family could continue being the essence of Armenian culture. The literary works of the period offered the image of an ideal woman for marriage: She was an educated woman who was to become a helpmate to her husband in a companionate marriage. A strong moral family was seen as the path to progress for the entire society.[17]

The Space and Shape of Women’s Struggle

The history of European women’s movements tells the story of organized activism for the improvement of the institution of marriage. As a consequence of this activism, women successfully put pressure on political bodies to adopt laws that were more favorable to women in matters of personal and marital status.[18] The Armenian women’s movement offers no example of organized activism. One has to turn to the rich literary heritage left behind by Armenian feminists and educated women to understand the scope of women’s campaign for the betterment of the institution of marriage and family.

The protagonist of the Armenian female novels was not the rebellious single woman disregarding societal gender norms and renouncing marriage as one comes across in fin-de-siecle European novels. Nor did the Armenian feminist of the time make attempts at “chartering her own alternate routes” through literature as Patricia Murphy has argued for the case of English New Woman novels.[19] In fictional writing, Armenian women very often echoed the same concerns voiced by reformers and male novelists, but they put women’s interests and women’s happiness at the center of their works. No matter how critical their novels were of the institution of marriage, they always expressed the authors’ positive attitude toward marriage as such. According to Sybil’s Bouboul, “A woman’s heart has only one thread – that is love; one life – that is the family; one mission – that is motherhood.”[20] Even Dussap with all her radicalism did consider marriage to be the “foundation of society”[21] and “a sacred treaty.”[22]

The tensions at various levels described above, and the unclear fate of a single woman with a highly limited choice for paid employment, made Armenian feminists very careful in developing a critique of marriage as an institution. As Deniz Kandiyoti has argued for the case of Ottoman Muslim women, in a society that offered women no shelter ouside the traditional family, it is hardly surprising that “at least initially women may have had a great deal to lose and very little tangible gain in following the steps of their more emancipated brothers.”[23]

The New Woman and Companionate Marriage

As it appears from women’s writings, feminists saw the freedom to choose one’s own life partner as the only way to achieve any reform. Forced marriage was unacceptable and harmful for the society because “when there is no love, there is simply the idea of responsibility, and that idea [of responsibility] only appears as a body without soul under the roof of marriage…”[24] A modern family was to be based on romantic love and the principles of a companionate marriage. Marriage was to be a union of “two souls, a mutual unselfish treaty to work for each other’s happiness, lighten one another’s burden, love each other.”[25] The companionate marriage based on romantic love promised to end harms women experienced in marriage and wrote about in their works (e.g. child-marriages;[26] complicated mother-in-law vs. daughter-in-law relations in extended families;[27] dowry, infidelity,[28] etc.) because it would allow women to enter into the union on equal terms with men.

Feminist authors saw women as capable of changing the institution of marriage if, prior to their entry into it, they themselves had reached perfection. Hence, as (future) wives and mothers, their protagonists had all the qualities women had been empowered to have through campaigns for access to education, paid employment and social/charitable work. The most important of these qualities was education. It was more and more the conviction that it was “not love for beauty and luxury that ruins families,” a belief widely spread at the time, particularly as criticism of the upper class, “but lack of educated women.”[29] Women’s education was to replace the dowry: “One can have an ideal family only when the woman’s dowry is her brain, diligence or some kind of profession, and endless delicate, feminine affection.”[30] Education would allow young women to enter the labor force, which would likewise give them more freedom in their choice for future husbands, and the ability to support themselves if they were to remain single.

The “modern” married young woman could no longer live in an extended family in which the older members stuck to traditional norms. Because they had matured through education, they were ready to be “good wives” and “good mothers” and were no longer in need of intervention by elderly women, such as the mother-in-law, in their household economy and child-rearing. Marie Beylerian’s protagonist, Almast, finds it impossible to remain affectionate to her husband when she is mistreated by her mother-in-law and subjected to her interference in the young couple’ life.[31] Yessayan’s Adile feels like a “house-maid” in the presence of her mother-in-law in the family. Both Beylerian and Yessayan render a loving relationship between husband and wife as impossible because of the conflict with mothers-in-law.

New Women, Old Homes

Women’s novels presented women as ready to be “New Women” and “New Wives” in reformed families, but implied that the “Old Homes” were not yet ready to accept them. Yessayan found the prevailing mood on progress and modernity incompatible with the persistence of old marriage values. To her, it was paradoxical that among the upper classes, “dowry in cash ranged from two hundred to five hundred gold, demanded by … young men, whose trousers, however, would widen or shrink in size to the dictates of Parisian fashions.”[33]

The New Woman was causing discomfort and fear. As much as the educated woman was admired, she was not a desirable wife even for the most educated man. Education caused misfortune for Yessayan’s Annik when she found herself in the “dangerous current” of developing a critical approach to society and marriage, and remained single.[34] Sybil’s brave and talented Bouboul was praised by young men, “and yet many of them would not have dared to marry her.” Having been educated in Europe, Tigran who was engaged to Bouboul, sarcastically expresses his uneasiness with his fiancé’s education:

Here comes the most fortunate of all young women of Constantinople… She has twenty thousand besides her beautiful eyes, and has admirers in the amount of hair on her head, but she does not like any man, because she is one of the art-lovers too. Do you know, Uncle, that being an educated woman in Constantinople is a warrant for becoming an old maid?[35]

Picturing the society as not yet ready for the New Woman was obviously women’s response for being subjected to constant male critique and negative images in the periodical press and literature. Sybil, for example, expressed her discontent with the way Grigor Zohrab portrayed women in his literary works. In these works, it appears:

as though women of mind and heart have disappeared, ceding to women who strive to change family and social life with their physical attraction only… Pay attention! In over forty of his short stories there is not a single woman who remains truthful, decent and loyal to her love with heart and mind.[36]

Women-Centered and Inclusive Visions of Change

In the depiction of this New Woman, the literary work of feminist writers generally differ from those of men in the way women’s personal happiness is situated at the center of societal happiness. As active as the New Woman is portrayed, social work and education are not considered as self-fulfilling or as substitutes for failure in achieving personal happiness. Moreover, women’s success in public life, as well as the well-being of society at large were seen as dependent on women’s personal happiness in marriage, because “[i]f the heart of a young woman is dead for her love, it [the heart] is dead for the world.”[37]

A discontent wife’s misery would become the misery of the husband as well. Matilda’s husband, who used his wife’s declining financial circumstances to force her into marriage with him, is portrayed by Marie Svajian as having an “unbearable” life and looking “abandoned” with no care.[38] Women’s suffering, albeit silent, could turn into a disaster for the husbands who had forced them into marriage. A girl marrying at the age of twelve in Yessayan’s short story does not protest loudly, but haunts her husband with her eyes, full of anger, pain and silent hatred, which affect the husband and become the reason for his death.[39] Another heroine of Yessayan, Arousyak, suffers greatly from being in a forced marriage so openly and demonstratively that her sufferings drive her husband to suicide.[40]

Relating Struggle for Change to the Bounds of Armenian Tradition

Feminist authors were very cautious not to cross the thin line between “improvement for the sake of the Nation” and “abandonment of Armenian traditional roles.” As much as feminists argued for change, they largely portrayed the “good” young woman as someone, who despite enormous sufferings, accepted hardship gracefully and obediently. Thus, in spite of their opposition to forced marriages, the protagonists of feminists’ works were obedient to the will of their fathers, ready to sacrifice their own happiness. In these works, romantic love emerges as equivalent to parental love. Sybil’s Bouboul does not break her engagement to Tigran out of fear of upsetting her father and goes through the incredible pain of choosing between two people most dear to her:

Day and night the gratitude and affection she felt for the old man competed in her heart with the passionate love she felt for Garnik, and if the former did not defeat the latter, the latter did not defeat the former either.[41]

Sybil justifies her pratogonist’s decision: “Who has ever seen the tear of an old man without torture of soul? Who would not be inclined to sacrifice her/his most dear yearning to prevent the sigh of that noble person [the father].”[42]

Dussap praises her heroine for valuing parental love over personal happiness, calling Siranoush “a martyr of love decorated by flowers of filial love.”[43] According to Siranoush, “He is the creator of my life and I am obliged to respect him forever.”[44]

Svajian’s rebellious Matilda fails to turn down her father’s request to marry an older man after the father puts psychological pressure on his daughter. She yields to the pleadings of her old father to sacrifice her own happiness to save the financial situation of the family. “She sacrificed her love to her parents,” Svajian writes about Matilda’s decision.[45] By picturing the protagonists as obedient daughters, the feminists ensured that their critiques would not be seen as an attempt to abandon Armenian culture. Feminist authors created a temporal (through diachronic historical comparisons) and spatial (through geographic comparisons) imagination in which the Armenian woman appeared as the most pure, most decent and most moral, also revealing their own sincere belief in the superiority of Armenian women (and culture). Reflecting on the turmoil that Bouboul felt confronted to choose between romantic and parental love, Sybil writes:

A novelist of a new school would have probably laughed at these lines, and a French woman would have perhaps called Bouboul “an idiot” for feeling conscience-stricken. Yet, a well educated young Armenian woman, of whom Ms. Geghamoff could be seen as a model, despite the highest degree of mental development and liberal thinking, would still listen to the laws of conscience. If she has had the misfortune of making a mistake because of lack of experience, she would have to pay for it with her life.[46]

Conclusion

The discussions and attempts to reform the family structure and institution of marriage during the 19th to early 20th centuries existed in a highly delicate framework because of the tensions between the clergy and laymen within the Armenian millet. Although both parties recognized the need for a law that would end the harmful traditions in marriage and family, up until the fall of the Ottoman Empire no consensus was reached on how to achieve this end. Women did not participate in the public discourse on reform in marriage and family. Rather, they articulated their concerns against gender inequalities in marriage and family through the voices of the fictional characters they created in their writings. Through these works, the Armenian woman emerged as educated, independent and ready to establish a new marriage and family culture. Feminist authors portrayed the happiness and progress of society at large as dependent on the private happiness of women, as much as women’s happiness was dependent on societal progress, an assertion that fused the lines between the private and the public, the personal and the political.