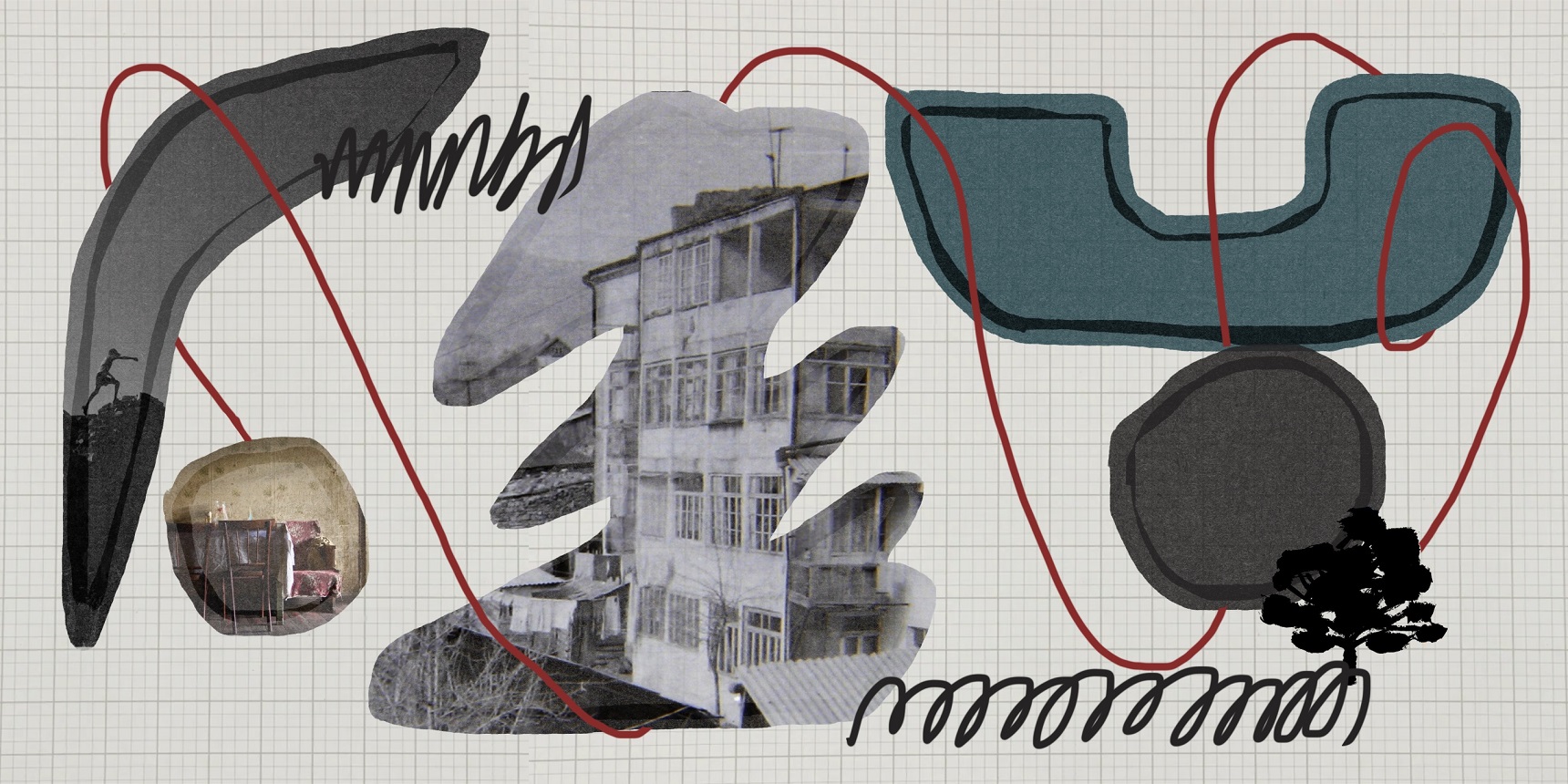

Visiting one post-Soviet state, you can then recognize it in all others – the similar patterns of urban planning and the identical buildings, structures, roads, pipes, wires, tiles, etc. However, an outsider delving inside under the extreme familiarity of the material environment finds an extreme “strangeness” of social interactions and practices. The [Outside In] series is about emplaced paradoxes and nuances. It spotlights the mundane in Armenia’s peripheral locations, where the seemingly unspectacular encounters with people and things allowing us to capture the unique features of the territory.

Outside In

Essay 2

The promise of transition from socialism to capitalism was that freedom from the bureaucratized, corrupt, violent, and ultimately inefficient state would bring happiness and prosperity. Yet, the long-awaited freedom backfired in small cities throughout the former Soviet Union. They fell into disrepair and neglect. They started being fetishized as material remnants of a bygone empire. As “left behind places”, “ghost towns”, “failed attempts to be urban” and “backwaters”, small cities are mocked and shunned. They are regarded as sick and dying; “normal life” continues elsewhere. “There is nothing there” — no money, no hope, no life — this is a common narrative about small cities. However, a place is never void. Regardless of what is left of their materiality and economy, small cities remain vibrant through gossip, stories, and legends about their heroes and mad(wo)men. Partly fictionalized, partly real, yet every word is true to the substance.

Siranush is a woman of undefinable age between 50 and 70. She has long braided grayish hair and wears a grayish sweater, her face is wrinkled. This is all I can basically say about her appearance. I never saw her up-close or spoke to her. She lives in a tower of a pompous orangish tufa Stalin-era house, with windows facing the main square. Everyday, from my window I see how she looks out from her window at the square, its vacant benches and non-functioning fountain.

For many years — how long no one exactly remembers — Siranush has not left her tower. Occasionally she speaks to some people, whom she recognizes by their voices. In her conversations she refers to events of a collective distant and not so distant past, which have very little connection to the current state of events. Though, generally, she is silent and still. At times so still that one might mistake her for a part of the city’s architectural ensemble, a Gothic temple gargoyle or a Baroque palace nymph. Depends on your preferences. From a lively woman entangled in daily urban routines, she turned into a detached observer:

Siranush is timeless or, rather, above time…

She lives in the universe of the past. Sometimes she feels like it is the 1970s, sometimes the 1980s. You never know. From her window, she used to tell stories of those years with such precision, such detail. Within them she was the mayor, factory worker, teacher…

We would stop and hearken, marveling at her skills as a storyteller… But she does not want to speak with us anymore, she became fossilized…

Siranush lives alone in darkness and cold. There is no gas or electricity in her apartment. After the Dark and Cold years of the early 1990s, she never cared to get utilities fixed. At least that is what people say, she does not let anyone in her home. To be sure, I have never seen light in her apartment. As the sun goes down, her cracked glass windows always remain pitch black. Her lonely dwelling brings to mind magical beings who create a parallel world of their own. We, who think of ourselves as “normal people” do not understand their world. Culturally, following the modern tradition, we tend to alienate people like Siranush, fear them, label them mad.

As with all local mad(wo)men there is a plethora of anecdotes about Siranush. The most popular one is about the battle for Siranush’s pension. More precisely, the battle to persuade her to receive her state pension. While the details vary, the general line is that she refused to sign papers and to interact with people. Some say Siranush developed a paranoia. Though, of course, she was never diagnosed with any mental disorder. For that, someone would have had to take her to the doctor. But she doesn’t even let her immediate family, her sisters, into the apartment.

She shouted at me. Told to go away when I knocked on her door. Accused me of trying to poison her or to drag her into a mental care facility.

Quite a justifiable fear, actually. Maybe, she is not that mad after all…

It took several years and the cunning art of persuasion on the part of several people, led by the former mayor, that broke her stubbornness (or tricked her?). Though, how and if she receives and uses her pension remains unclear to me. She doesn’t travel or pay for utilities. Food is “delivered” to her by children as a sort of donation from their parents and grandparents. Several times I saw how Siranush lowered a plastic bag tied to a rope out of her window. Children fetched her matnakash and matsun. Then she pulled the rope back in.

“Doesn’t she look like a fairytale princess, locked up in a tower?” my university friend, who had come to visit, asked rhetorically over morning coffee. Indeed. But rather than a fairytale that promises us a happy ending, to me she is a character of a tragic saga. Within it, Siranush is not a protagonist or antagonist, she is an allegory. “Cared for” and “sustained”, she was at the same time violated by her husband who regularly beat her. After his death, shortly following the collapse of socialism, she became free in all respects. Yet, the fracture of her usual life drove her completely mad. Not so uncommon for people living the post-Soviet transition. To some it brought wealth, to others despair. Those lucky ones who made a fortune and rose to power in the turbulent years, arrogantly call their counterparts “losers”. But it is these “losers” who constituted the majority of the population facing deprivation and scarcity, deaths of family members from violent crimes and alcohol or drug abuse, as well as dealing with the loss of dignity and sense of purpose as a result of unemployment and sudden poverty. Although the rising levels of social polarization were omnipresent, small city dwellers seem to have suffered more due to the lack of access to resources and embeddedness in global networks.

News informs of wars with spectacular destruction and death; in small cities there is a lack of the spectacular. There is peace and quiet. Buildings crumble and nature creeps to take over. Active people leave to make a living, the rest adapt and survive. Some slowly go insane, but most unremarkably live out and die ahead of schedule without access to proper care and healthcare. An interlocutor once told me about the occasion of his neighbor’s death: “I went to take the trash out and took out my neighbor [the dead body of the neighbor] along the way.” The bare cynicism of the situation against the backdrop of the narrator’s mundane tone gave me shivers. To be fair, this sinister standstill is not only shaped through external (non)action. It is also about internal resistance to moving forward, sticking to tradition, opposing newness and any type of improvement with at times fierce madness. Resembling Siranush’s refusal of her pension.

***

P.S. As I observed Siranush, she might have been observing me. We both observed the city. Two women in windows, one opposite the other. Who knows, one day we might discover Siranush’s own writing about her city — an Inside Out story — about the collective us, the “normal people,” whatever that means.

See all [Outside In] articles here