Visiting one post-Soviet state, you can then recognize it in all others – the similar patterns of urban planning and the identical buildings, structures, roads, pipes, wires, tiles, etc. However, an outsider delving inside under the extreme familiarity of the material environment finds an extreme “strangeness” of social interactions and practices. The “Outside In” series is about emplaced paradoxes and nuances. It spotlights the mundane in Armenia’s peripheral locations, where the seemingly unspectacular encounters with people and things allowing us to capture the unique features of the territory.

Listen to the article.

Outside In

Essay 18

When visiting new cities, we often arrive with preconceived non-negotiable checklists on our itineraries. Take Yerevan, for instance. Republic Square, the Cascade Complex & Cafesjian Center for the Arts, the Matenadaran, Tsitsernakaberd, and the Vernissage Market would most probably be among the top attractions, serving as a visual shorthand for the city, symbols of Armenian identity, and photographic proof of having been there. Without attempting to diminish the significance of these landmarks, one might ask: do they truly allow us to understand Yerevan?

Public culture favors the spectacular, framing our expectations for things out of the ordinary, those which are “worth” noticing and remembering. While living a mundane life with its simple encounters—like Didi and Gogo, the characters of Samuel Beckett’s play “Waiting for Godot”—we wait for that which might never come. Major sights are like historic events, rare and unrepresentable occasions in the otherwise uneventful flow of time. As argued by historian Susan Crane, it is the perceived nothing (out of the ordinary) rather than something which surrounds us:

Nothing happens. It happens all the time… By definition it is not worth noticing and certainly not worth remembering and therefore unlikely to become anything historically significant… It also provides continuity: Nothing [was] happening, and Nothing is still happening.

Tourist attractions systematically devalue the details that constitute the complexity of the lived urban experience. Marginalized or “uneventful” histories, mundane practices, and DIY structures usually receive minimal tourist attention unless represented as a spectacle or “authentic” voyeuristic experiences. This bias results in a self-reinforcing cycle where visitors see what the previous ones have deemed important, creating a narrow, often exoticizing perspective on what constitutes cultural significance in cities.

One day in late March 2025, I woke up with a strong desire to revisit southern Syunik. So, living according to the Russian proverb, “a hundred miles is not a detour for a rabid dog,” and without further overthinking, I indulged on a weekend road trip to Meghri with stops in Agarak, Kajaran, Kapan, Hin Shvanidzor, and Goris. As amazing as the murals are of Meghri churches with their mixture of Christian and Islamic traditions, or Goris’ unique architecture and the now abandoned cave dwellings, it is the subtle details of Syunik’s cities which captured my attention. The devil is always in the detail, and it is those unassuming materialities that will constitute the narrative of this essay.

Outdoor Laundry Lines

In Armenian cities, laundry lines stretched between apartment buildings tell stories that visitors rarely pause to read. The tradition of hanging laundry outdoors is grounded in Armenia’s warm and dry climate, as well as reinforced by the shortage of indoor space in Soviet-era apartments. The arrangement of items follows unspoken rules developed over decades, with garments organized by size and type rather than color, embodying a communal aesthetic of shared routines.

Laundry on display creates inadvertent intimacy between neighbors. Representing both necessity and cultural continuity in cityscapes, this practice blurs the line between private and public spaces—offering glimpses into very private lives conducted in public spaces. Though the practice of hanging laundry outside is common throughout the country, perhaps its most picturesque manifestation can be witnessed in Kapan, where brutal multi-story cascading Soviet apartment blocks constructed on the high bank of the Voghji River are connected to each other by multiple layers of laundry lines. Beyond those connecting buildings, some lines are attached to special poles which follow a single design, hinting at deliberate amendments to urban planning. A neatly ordered geometry of white sheets, colorful garments, and even shoes swaying in the wind against the stillness of mountain slopes intertwines the dynamic power of movement with the quiet authority of permanence. In the capital of Armenia’s most important mining region, this practice speaks of cohabitation between tradition and modernity.

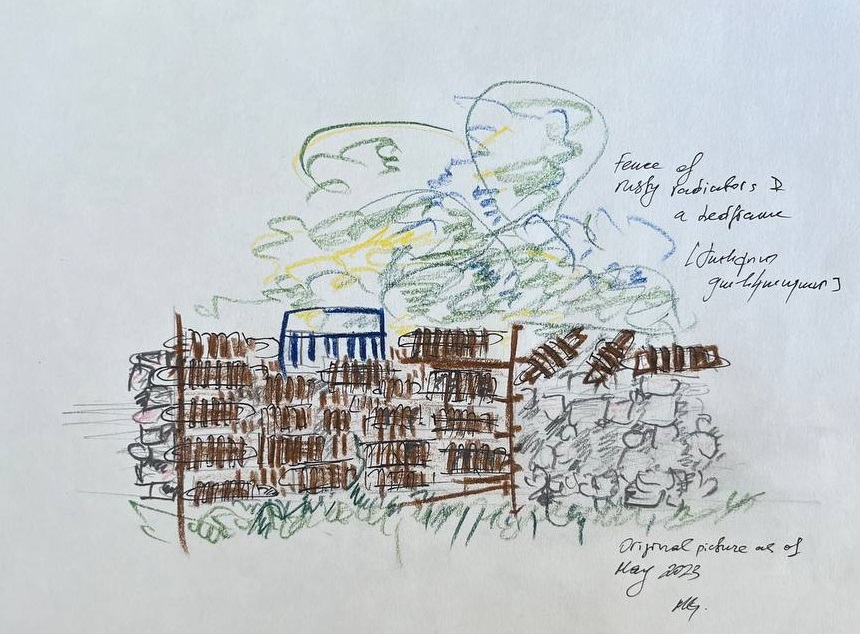

Rustweaving

Weaving, including carpet weaving, is a hallmark of Armenian culture. In a playful twist on this tradition, I call the common DIY practice of constructing objects with recycled metal “rustweaving.” Weathered by time, metal gains a rich patina of rust in shades of amber, sienna, and ochre, remarkably similar to the hues found in Armenia’s natural landscapes and art, such as in Armenian textile and ceramic color palettes.

While structures made from metal appear in various Armenian settlements, in my view, this art/architectural form has reached its peak in Kajaran. Within Kajaran’s borders there are several “shantytowns” with structures built entirely from radiators, cords, pipes, and metal barrels, likely once used for storing and transporting chemicals. On some of them, words can still be traced – “Lukoil,” “Yokoil,” “Agrinol,” and others. For construction purposes, the metal barrels are flattened into sheets and ingeniously joined together; either woven through drilled holes with wire or fastened with large staples. What might appear haphazard to an outsider actually follows an established local construction method that has been practiced and refined for decades. Kajaran’s residents have developed a sophisticated understanding of working with metal barrels, knowing exactly where and how to cut, (un)fold, and join the metal to create sturdy structures that withstand the region’s harsh mountain climate.

The DIY rustweaved structures serve multiple purposes: addressing the community’s needs for affordable shelter and storage while simultaneously, if unintentionally, creating a distinct identity for Kajaran through transforming industrial waste into functional architecture. The practice represents a unique intersection of industrial recycling, an unarchitected tradition of construction, and cultural expression that deserves recognition as a notable example of spontaneous yet durable innovation.

Rails Leading Nowhere

In Meghri and Agarak, one stumbles upon the remnants of the Yerevan-Nakhichevan-Baku railway line. Once a symbol and promise of connectivity, these tracks now stand as manifestations of conflict, with their purpose eroded alongside the deteriorating relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Some rail sections remain partially intact, while others have been dismantled. The metal frames were distorted or foraged for scrap. In some places, the rails have sunk into the ground, buried beneath layers of dust, grass, and concrete. Their presence is revealed only to keen observers through faint impressions. Elsewhere, they reemerge from the ground like the skeletal remains of ancient beasts, corroded, dismembered, and weathered by time. Decay has claimed the wooden sleepers, splintering them into fragments, while rust spreads across the metal, turning once-smooth surfaces into rough, red-brown rot. Weeds and shrubs have taken root between the tracks, overgrowing the lost pathway of connection.

Near the entrance to Agarak, Soviet-era industrial infrastructure looms over the cityscape. A set of ruined railway tracks stretch over the river gorge, leading toward the decaying factory grounds. Atop its main building there is a red star alongside a large, faded plaque bearing a barely legible Russian-language Soviet slogan: “[Our] aim [is] communism.” The ideological promise of communism and the supposed friendship of the peoples it sought to forge was never achieved. And even the road to that vision, much like the railway itself, has now rotted away. Rails are a physical reminder of how grand historical narratives can fade into the landscape, leaving communities to navigate the material remnants of failed utopian visions.

Drawing by Maria Gunko.

Maria Gunko is a DPhil Candidate in Migration Studies, Hill Foundation Scholar at the School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography University of Oxford. Since 2023, she has joined Yerevan State University as a Visiting Professor. Maria holds an MSc and Kandidat Nauk (Russian post-graduate degree) in Human Geography.

Maria’s research interests lie in the intersection of urban studies and social anthropology, including ethnography of the state, infrastructures, and urban decay with a geographical focus on Eastern Europe and the Southern Caucasus. She is the co-editor of one monograph, author of over thirty scientific articles and op-eds.