[Beyond Borders]

This column explores the key issues shaping life in the South Caucasus, focusing on how the divergent paths of Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan reflect the region’s complex histories, economic developments, and political shifts. While new generations in these countries grow more isolated from one another due to language barriers and conflicting national trajectories, the same is true for local policymakers, who are often more familiar with distant capitals than their immediate neighbors. Each nation seeks its own path, sometimes in conflict with others, while international actors often treat the region as a whole, reluctant to craft policies specific to individual states. Drawing on personal experience with the region’s revolutions, conflicts and transformations, Olesya brings you Beyond Borders—a column exploring how decisions made in one corner of the South Caucasus impact all who live there.

Listen to the article.

These days the air in the South Caucasus feels thicker than it has in decades, not with heat or smoke, but with the slow suffocation of freedoms once taken for granted after the Soviet collapse. In Georgia, each week seems to bring a new restriction targeting liberal values while Azerbaijan shows international humanitarian organizations to the door. Against this backdrop Armenia stands—tentatively, precariously—as a lonely isle of pluralism. But for how long?

In Tbilisi, Monday mornings have begun to feel eerily scripted. For more than a month now local television has devoted hours to the parliamentary commission scrutinizing episodes from the nearly decade-old administration of Mikheil Saakashvili. Though that government left office in 2012, the current ruling Georgian Dream party appears determined to rewrite the chapter with the vigor of a regime settling old scores. Each week, former officials, civil servants and even aggrieved relatives of those affected by past policies are summoned, dissected and paraded through parliamentary hearings, an echo chamber of retroactive accountability.

All of this plays out amid a sharp and deliberate turn away from liberal democracy. Georgia’s parliament, boycotted by all opposition parties after a disputed election, now functions like an unhinged printing press—churning out a steady stream of repressive legislation. Since last fall, lawmakers have banned so-called LGBT propaganda, and more recently erased the word “gender” from official state documents. Come May, collaboration with foreign foundations may carry prison terms. And in the coming days parliament is preparing to enforce mandatory registration of all foreign grants, a bureaucratic mimicry of Azerbaijan’s long-standing control tactics.

To civil society organizations in Georgia these developments feel like the prelude to an obituary. Legislative amendments have erased the previous requirement that NGOs be consulted in policymaking. Long-time partners in the Georgian regions now shy away from renting venues or attending events. Whispers of fear replace public dialogue. It is a surreal reversal for a country once hailed as a beacon of post-Soviet civic engagement and a favored recipient of Western support.

The Azerbaijan Playbook

Azerbaijan, of course, has already walked this road. The dismantling of its civil society infrastructure began over a decade ago. The space for activism shrank, and one by one the lights went out; some activists left the sector, others the country. The ones being jailed today belong to a younger generation raised in the shadows of repression. Those who remain free keep their heads low and voices lower.

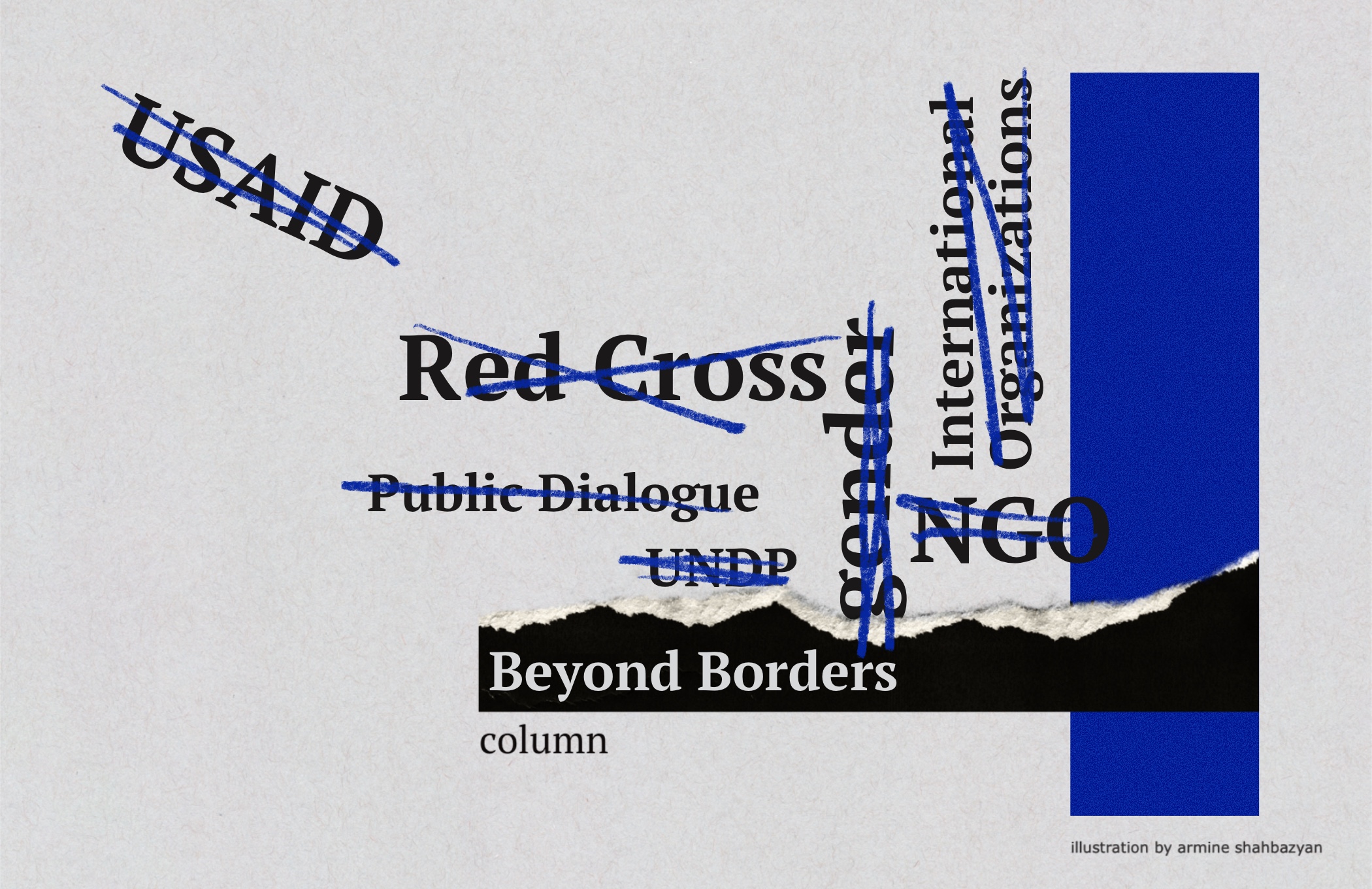

Now Baku is tightening the noose further. Several international organizations, including some focused solely on humanitarian work, are preparing to shutter their offices by year’s end. Among them is the International Committee of the Red Cross, which closed its operations in Stepanakert and nearby cities last year. More surprising was the quiet withdrawal of the United Nations Development Program—once a central player in post-war mine-clearing efforts near Nagorno-Karabakh following the 2020 war. Many Western embassies had pinned their hopes on UNDP as a bridge, believing that through its programs at least some channels of engagement with the Azerbaijani government might remain open.

Azerbaijan’s leadership claims it no longer needs the development programs once heralded as vehicles of cooperation with the West. Baku openly spreads suspicion that these groups may be aiding activists and journalists without submitting to state oversight. Long before President Trump defunded large swaths of USAID programs, Azerbaijani authorities had already raised objections, and eventually expelled the agency altogether. Moscow’s NGOs were also shown the door, though their absence stirred far less concern than the fading presence of Western initiatives.

Armenia’s Quiet Defiance

In this regional atmosphere of democratic retrenchment Armenia remains something of an anomaly. It does not expel NGOs or curtail international partnerships. Its civic space, while imperfect, still breathes. But the question is no longer whether the pressure will come, but whether Armenia can endure it.

From a distance the prognosis may not inspire hope. Armenia is small, landlocked and burdened with fraught borders: a history of war with Azerbaijan to the east and a long-sealed border with Turkey to the west. To the south lies Iran, whose theocratic rigidity offers little comfort. To the north and on paper Armenia remains an ally of Russia—a country that has spent the last three years waging war in Ukraine and tightening the screws on its own civil society.

Looking outward for help is a gamble. The Trump-era leadership cast its lot with global illiberalism, and Europe—stretched thin by the war in Ukraine and its own security reawakening—is still finding its footing. External support, at least in the near term, may prove scarce.

And yet surrender doesn’t come easily to Armenia. Nor would it be universally accepted. There are voices, domestic and foreign, that wouldn’t blink if Armenia quietly acquiesced to a more obedient, inward-looking posture. But the country’s modern history suggests otherwise: it is ill-suited for authoritarian quietude.

The resistance, such as it is, comes from within. As one departing ambassador once remarked, in Armenia, three people will hold five opinions and each will argue theirs to the bitter end. As an Armenian bureaucrat once told me, “You simply can’t govern this country without listening to its disagreements.” Manipulation is possible—through propaganda, loyalty-driven think tanks and media messaging—but the effect is short-lived. The same goes for decisions imposed by external actors. Eventually cracks form. People protest. Elections are held. Sometimes revolutions follow.

In that sense Armenia may not have a choice. Its path forward lies in preserving the very freedoms that have helped it weather crisis after crisis—from the challenges of post-Soviet transformation to the war of 2020. Pluralism isn’t just a principle here. It may be the last mechanism left for national resilience.