Listen to the article.

In a world marked by ongoing wars, increasing militarization, and media colonization shaping the narratives of contemporary and historical conflicts, the curator’s role has become more vital, critical and complex. With cuts to art and cultural funding in Western countries, rising censorship, and mounting ideological pressures, the landscape of contemporary artistic expression is being reshaped—forces that curators must regularly confront and challenge.

The exhibition “Victory Over the Victory”, curated by Sona Stepanyan and Natasha Dahnberg, represents one response to these complexities and dominant narratives. It takes a critical stance on the notion of “triumph,” presenting works that reflect on conflicts ranging from World War I to contemporary wars in Artsakh, Ukraine and Afghanistan.

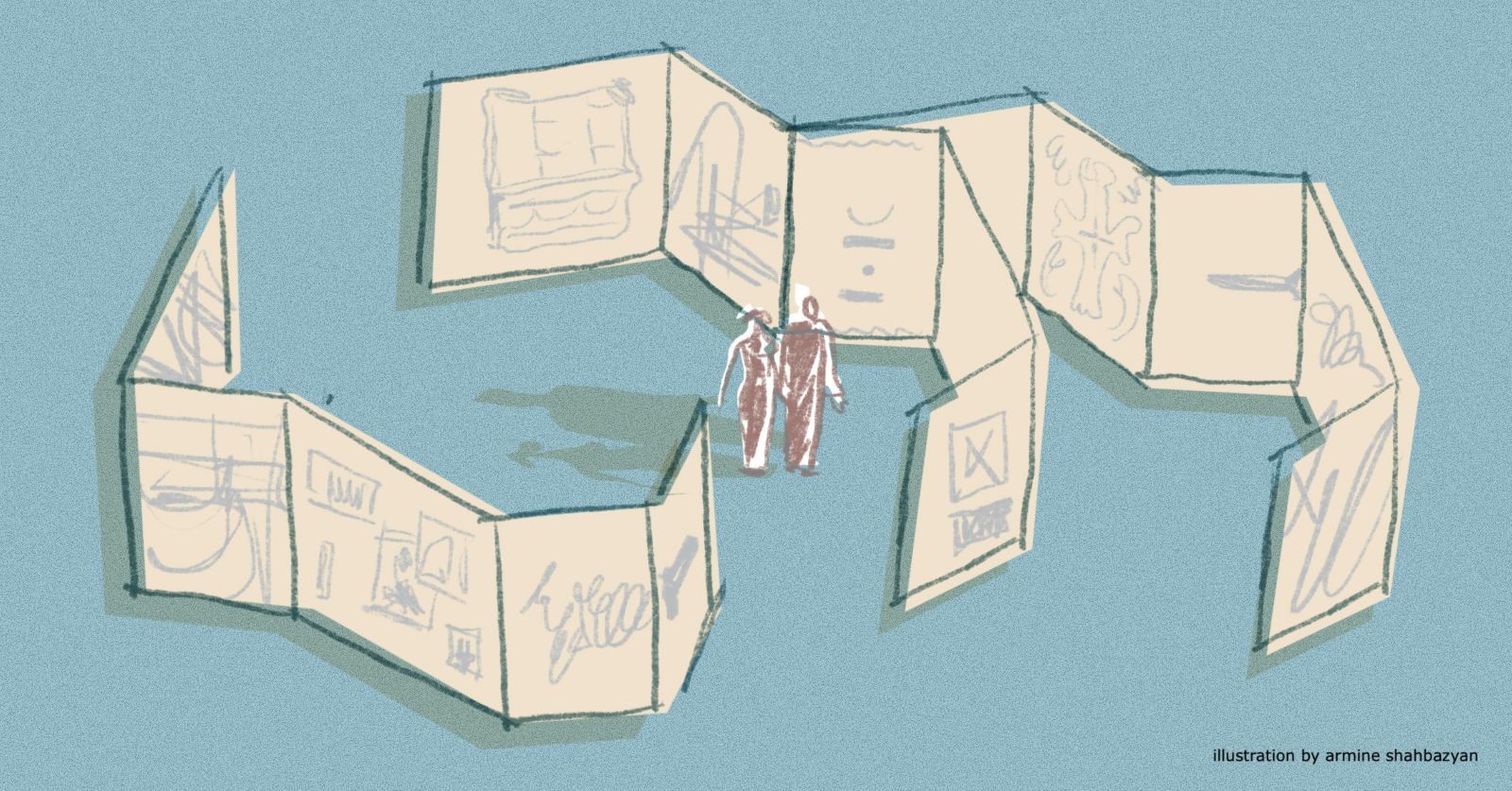

The exhibition, which opened on February 14 at Havremagasinet in Boden, Sweden, is the first iteration of the show launched by the two curators in Uppsala last year. It brings together works by over 20 international artists, including Mkrtitch Tonoyan’s audio installation-monument “Roll Call” (2016)—commemorating by name 15,000 Canadian soldiers killed in battles from World War I to Afghanistan. Also featured is a selection of in-situ imprints created at Dadivank Monastery during the 2020 Artsakh war by Vahram Galstyan, Maïda Chavak, Anush Ghukasyan, and myself, later assembled into the collective installation “40.1616°N 46.2882°E” by AHA Collective.

As the exhibition travels to Boden, a northern city with active military bases and Sweden’s second-largest immigration center for refugees and asylum seekers, the curators’ work becomes even more complex and significant. “We were mindful not only of shaping the audience’s experience within the exhibition space but also of the fact that many visitors have firsthand experience of war and conflict,” shares co-curator Sona Stepanyan. Drawing from Swedish writer Malte Persson’s book titled “Undergången” (The Fall)—a collection of poems reflecting on humanity’s precarious existence—the metaphor served as a foundation for the curatorial vision. “Victory Over the Victory” refuses to see war through the simple dichotomy of winners and losers; instead, it interrogates past “triumphs”, amplifies voices of current ongoing conflicts, and questions the ideological legacies that conflicts leave behind. “We wanted to challenge the hierarchies and binaries embedded in militaristic thinking—such as war versus peace, victory versus defeat, just versus unjust, ally versus enemy,” explains Stepanyan. “We also wanted to explore and show the ways that war and politics remain deeply entangled and how preventive warfare is still increasingly legitimized on an international scale.”

At the time of its curation, geopolitical tensions were at a peak, with ongoing discussions between global leaders on military aid and strategic alliances. One of the exhibition’s most striking works—a live radio broadcast from Ukraine’s Kiss FM by Swedish artist Mathilda Frykberg—bridges the gallery space with the reality of war, making conflict an immediate and shared experience for the audience. The curators faced the challenge of representing war’s inherent incompleteness without reducing artistic expression to mere political statements or commodities. They chose to push the boundaries of artistic expression by rejecting traditional war photography, graphic representation, and documentary practices. Instead, they favored works that abstract, recontextualize, and question what war means in the contemporary imagination. “In addressing the commodification of art and the pressures of excessive representation, we intentionally selected works that also engage with these concerns through their intrinsic constraints. We wanted to explore diverse artistic strategies that challenge the passive consumption of war imagery. Some notable artworks in the exhibition exist beyond conventional object form: an audio work by Armenian artist Mkrtich Tonoyan, a site-specific wallpaper print by Afghan artist Aziz Hazara, and a series of cell phone videos by Ukrainian artist Zhanna Kadyrova,” highlights Stepanyan.

By bringing together multiple perspectives—those of witnesses, the silenced, and the absent—the exhibition aimed to create a multidimensional, multigenerational, and multicultural discussion on war experiences. This holistic curatorial approach required extensive research and literature exchange between the two practitioners to refine their conceptual framework. They engaged in close conversations with artists, ensuring that their works maintained integrity while fitting within a broader context. “I undertake large group exhibitions only every few years, as I believe they require in-depth research, a strong understanding of context, and a clear curatorial voice that takes time to build,” explains Stepanyan. “Fortunately, these values align with the curatorial practice of my co-curator, Natasha Dahnberg. Together, we engaged in thorough conversations with the artists and between ourselves, ensuring that we maintained the exhibition’s internal logic throughout the process. It was crucial for us to be confident, honest, and transparent—with ourselves, the artists, and the hosting institutions.”

The curators prioritized ethical considerations in their selection process, favoring critical engagement over spectacles of suffering. By including Swedish artists, they ensured the exhibition wasn’t solely focused on “distant wars.” Their research at the Uppsala Museum revealed Cold War-era propaganda posters, adding a historical layer and sparking a dialogue with the contemporary context—challenging viewers to see war as a continuum rather than isolated events. Among these works was the pacifist poster “Desecrate the Flag” (1967) by Carl Johan De Geer, which proved so provocative that police confiscated and destroyed much of its original print run. Now displayed inside a contemporary art exhibition, this piece from the museum archive stands as a historical testament to Sweden’s resistance to militarization.

As cultural funding shrinks worldwide and political influence over artistic expression grows, “Victory Over the Victory” stands as both a timely and necessary intervention—one we hope to see replicated in other countries. “We see this project as urgent, especially given the absence of institutional voices on these topics in the contemporary art field,” Stepanyan asserts. The Stockholm-based Armenian curator’s observation resonates with local Armenian institutions, especially regarding their lack of public dialogue about the fall of the Republic of Artsakh in 2023 and the sociocultural and geopolitical consequences of the forced displacement of the entire indigenous Armenian population from their native homeland. The curators’ decision to exhibit imprints from Dadivank Monastery, part of the collective installation “40.1616°N 46.2882°E,” brings a deeply personal and political dimension to the exhibition while interrogating the role of imagery in conveying the realities of war. “We sought works that don’t overtly depict war, tragedy, or suffering, yet powerfully reveal what is often hidden, abstract what is usually explicit, and destabilize the notion that war can ever be fully ‘understood’ through a single image,” says Stepanyan.

The images of Vahram Galstyan, Anush Ghukasyan, and me during the evacuation of Karvajar on November 13, 2020, carry great importance. “During the wars in Artsakh, I found myself unable—mentally, ethically, and even physically—to speak about it as a curator. The experience was too personal, too immediate; I felt it on my own skin, knowing intimately what my family, my artist friends in Armenia, and all Armenians were going through. When the opportunity arose to curate this exhibition in 2024, I thought that perhaps, this time, I could create some distance to engage with the subject. I decided to include a piece from Armenia. I had been following the work of AHA Collective and was aware of the journey and the creation of this piece. It holds immense significance for me,” shares Stepanyan.

Four practitioners from Armenia and the diaspora created this work to document the territory of Dadivank, specifically capturing the moment of the impromptu pilgrimage to the monastery during the evacuation of the region on November 13, 2020. Anticipating potential alteration or destruction of this Armenian medieval heritage site by Azerbaijan, the artists turned to an archaic documentation method: reproduction by contact. A year later, these individual imprints were carefully assembled into a collective installation by my curatorial practice, AHA Collective, and showcased directly to the Armenian public at the Cafesjian Center for the Arts in the exhibition “Hanging Garden: Dadivank and Beyond,” alongside other mixed media works. The installation, comprising 35 clay and paper imprints, aims to revive the physicality of the place by sharing the materiality of the monastic architecture through handmade reproductions of its sculpted walls. It becomes a vessel of transmission and memory, offering alternative approaches to preservation. The work presents new forms of collective engagement and co-creation practices—in-situ, rooted in the territory and local context. “This work is deeply charged with the place and its memory—it is not just a symbol but the physical imprint of those walls, carrying their history within its material form. I had the chance to touch those walls again after my last visit to Artsakh in 2019. Even as I write this, I feel goosebumps once more. For me, the work brings a deeply personal and human dimension to my curatorial work, making the exhibition both tangible, intimate, fragile and real,” shares Stepanyan.

The curator notes that the exhibition was conceived during a moment of significant geopolitical change—Sweden’s decision to join NATO in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. “The cultural community largely responded through articles, public discussions, and activist interventions,” she observes. This shifting political landscape provided an important backdrop for the exhibition, featuring works that directly address Sweden’s evolving stance on military alliances and global conflicts.

The curators used text, guided tours, and multimedia materials to bridge local and international perspectives, while connecting historical and contemporary viewpoints. Text plays a central role in providing context and inviting reflection. Stepanyan notes that the exhibition was intentionally text-heavy, featuring detailed labels and a bilingual booklet that offered deeper insights into the works: “We wanted to provide in-depth contexts rather than relying solely on visual storytelling.” This approach was essential given the geographical and cultural distance between the exhibition and the regions the works address.

In a world where militarization seems increasingly inevitable, “Victory Over the Victory” stands as a form of resistance. The exhibition highlights our growing desensitization to war’s inevitability, challenging viewers to reconsider how they engage with representations of conflict. “We wanted to create a space for dialogue. People need space to discuss difficult and disturbing matters, share their thoughts, challenge their views, and listen to others,” Stepanyan concludes.

As world powers attempt to monopolize truth and silence dissent, curators like Sona Stepanyan and Natasha Dahnberg have co-created a vital exhibition that offers new perspectives on our ongoing polycrisis. The exhibition serves as a space for critical reflection, both for the public and artistic community, where direct and indirect experiences of war across geographies resonate with one another. Their curatoratorial approach reveals that discipline transcends artistic and scientific dimensions, embodying acts of resistance, engagement, translation, and hospitality. The curators resist and repair narratives that seek to erase or distort human experience. While this practice of navigating the intersection of art, politics, and society is still developing in the local Armenian scene, creating a curatorial network of diaspora- and Armenia-based curators could advance the discipline in Armenia and strengthen the presence of Armenian contemporary art both locally and internationally. Such initiatives would harness soft power and cultural diplomacy, positioning Armenian contemporary art as a force for dialogue, visibility, and influence. May this collaboration seed a growing network that fosters what I define—following Edouard Glissant’s philosophy of relation—as an “Armenian Archipelagic Thinking”, one that embraces organic connections across Armenian geographies, temporalities and perspectives, rather than being confined to an Armenia-Diaspora binary, past-centered and victimized narrative.

Et Cetera

Women, Peace, Art: Breaking or Reinforcing Stereotypes?

The "Women, Peace, Art" exhibition in Armenia showcased eight female artists addressing peace amid war's haunting memories. While ambitious, the exhibition struggled with essentialist portrayals of women, often reinforcing stereotypes instead of challenging them.

Read moreArchitecting a New Language of Sustainable Practices in Armenia

Amid Yerevan’s chaotic development, grassroots initiatives led by local and diasporan architects are reimagining Armenia’s architectural landscape. By fostering dialogue and hands-on learning, they aim to rethink building practices and promote responsible, sustainable approaches to architecture.

Read moreArmenian Art and the World: Insights from Festival Week-end à l’Est

The 8th Festival Week-end à l’Est celebrates contemporary Armenian art through a multidisciplinary program across six venues in Paris. Featuring renowned and emerging artists, the event explores themes of identity, displacement and cultural dialogue, bridging Armenia’s vibrant artistic scene with global audiences.

Read moreStereotypical Armenians and Armenian Stereotypes in Film

With a spotlight on Sean Baker’s film "Anora" that won the top prize at the Cannes Film Festival this year, Sona Karapoghosyan examines how evolving yet often reductive depictions in American cinema shape perceptions and cultural narratives about Armenians.

Read moreEVN Report Art Digest

ARTINERARY: May 5-14

As AI reshapes creativity and replaces human labor, much contemporary art feels stagnant—recycled, safe and system-bound. A revival, if it comes, will rise from urgent, crisis-driven contexts like Armenia, where meaning still demands to be made. In this edition of ARTINERARY, Vigen Galstyan spotlights exhibitions where artists confront technology, identity, and post-war trauma in works pulsing with transformative promise.

Read more