From emerging Armenian artists across the globe to Armenian-American talent in the United States, [Art Speak] will spotlight the dynamic and diverse Armenian art world and more.

Listen to the article.

Working from a gemütlich old-style walk-up apartment in New York’s East Village on a warm spring day, Judith Simonian prepares for her upcoming solo exhibition at JJ Murphy Gallery. Titled “The Human Element: Huddled and Still,” it will show off 15 or so of the Los Angeles-born artist’s latest small and medium-scale works.

Today, the sun shines down onto Simonian’s fire escape. Carefully arranged brushes and paint tubes decorate a white desk table. Everything about the live-work space quietly exudes creativity. Simonian has made fresh coffee and laid out an assortment of French pastries for me: the moment feels more like family than an official studio visit. Whip smart, at 70 Simonian cuts a striking figure and sports strong avian features. She quickly takes in curatorial and writerly queries and answers them incisively. Unsurprisingly perhaps, with each viewing I find myself increasingly attracted by the rare combination of layered, visual beauty and intellectual refinement of her acrylics on canvas. They typically display vibrant colors—including bright candy reds, sky blues, chalky purples and deep violet hues. These overlap with pastels in unlikely combinations unique in the contemporary art world. In the past, Simonian has cited artists such as Philip Guston, Pierre Bonnard and Charles Garabedian as having influenced her work, but today the late Italian still life master Giorgio Morandi comes up several times.

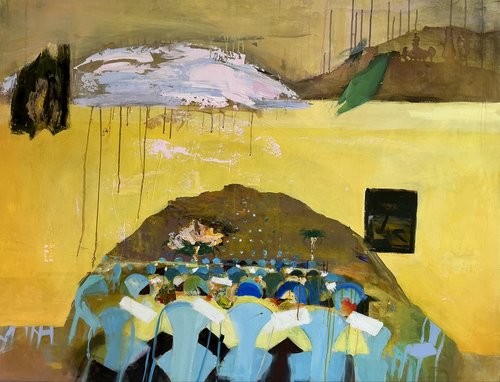

As I settle into my chair, Simonian has already mounted the largest of a dozen or so paintings that she will show me over the better part of two hours: “Enter the Mountain Yellow.” An empty banquet table stands front-center of this intricate 50 by 66-inch canvas, mysteriously foreboding in its hushed silence. One wonders where all the guests have gone. Or have they yet to arrive? Like Simonian, I have always found something disquieting about banquet tables. As she elaborates on the topic we share a small meeting of the minds: “There’s something eerie about them, their formality perhaps,” agrees Simonian. A small but intricate design to the back left of the table recalls a Klimt or Hundertwasser design. I assert that as someone trained in literary theory, I have noted that her works often contain the visual equivalent of mise-en-abyme. Borrowed from medieval heraldry by French Nouveau Roman guru Alain Robbe-Grillet in the 1960’s, the term indicates a story-within-a-story, or in Simonian’s work a painting-within-a-painting as it were. Here I find it in the upper right hand of the banquet table: a small black rectangle which catches the eye. It might be a space for people or things to either arrive or leave by, or perhaps even be teleported. “It looks like a book,” I suggest. Simonian agrees then adds, right on cue: “It’s an exit ramp, actually.” I ask her to elaborate. “The painting,” the artist goes on, “harkens back to a restaurant I saw years ago which was literally built into the mountain in Itri.” The mention of this beautiful town wedged in Italy’s Lazio region between Naples and Rome and known for its lush olive groves instantly grabs my interest: “There was a restaurant built into the rockface when I was there,” Simonian explains, “and at one point it looked to me as if a line of waiters was literally disappearing into the rock, into the void.”

Enter The Mountain Yellow, 50x 66 inches, acrylic on canvas, 2023.

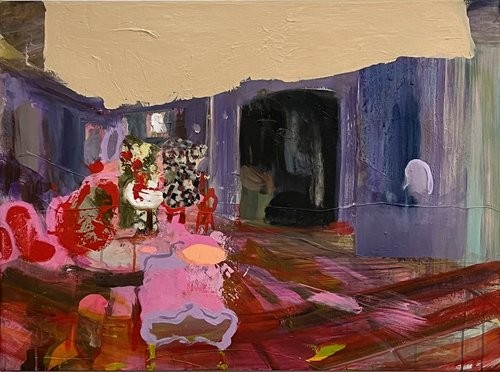

In the painting, empty chairs surround the banquet table, but no humans appear. Abstracted to a purely color field level, the work also looks to me like a series of three or four successive blankets, perhaps covering a huddled human form of some type. And then one cannot help but be seduced by the unique shades of sun yellow and the subdued dark golden hue in the far background, like a setting sun. The exit ramp/book functions as a void which leads to the unknown. Nodding, Simonian cheerfully grabs another smaller work “Inside Out,” which depicts the interior of a restaurant. Its bright cheerful reds blend into purple and pink pastel hues which instantly delight. As in other pieces in the upcoming exhibition, this one also appears devoid of people. But on closer examination, an ominous black room painted where one might expect a wall or passageway, draws in the viewer’s eye—a larger version of the exit ramp in “Enter the Mountain Yellow.” Inside it, a barely detectable white shape stands ghost-like. “This,” Simonian says excitedly, “is an indeterminate space. I think perhaps that here it represents the human subconscious.” Or the artist-at-hand’s subconscious, at the very least.

Inside Out, 28x 38 inches, acrylic on canvas, 2023.

***

In what I might term the uniquely Simonianesque in her works, lies an ever-quixotic element which might appear psychologically darker in another artist. In her case, however, she masterfully inserts them so as to appear more matter of fact than psychologically askew. In the past these have included the larger-than-life perspective and dimensions on a Berlin basketball court in “BAU Berlin,” (2021); a fleshy redheaded muse that boldly juts out of the port side of a large ship in “Sperlonga” (2016); and in “Resting on Her Side,” (2024) a tanker that sinks, floats, or defies gravity—depending on which way you hang the rectangular painting. And in a career that has spanned several decades now, Simonian has had several successful incarnations. An active participant in LA Street Art inspired by her new urban environment of graffiti-covered walls, she exhibited at and was on the Board of Directors of Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE) and the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art in the 1980s.

Simonian’s work has spanned genres ranging from experimental and conceptual art to her current incarnation as a figurative painter whose work dissolves into painterly abstraction. Since 1984, she has exhibited at leading venues such as The New Museum and PS1 Contemporary Art Center/Museum of Modern Art in New York City, the Montclair Art Museum in New Jersey, the San Francisco and Santa Barbara Museums of Art in California, as well as Kai Hilgemann Gallery in Berlin. In 2022-2023, 1GAP in Brooklyn curated a rare 12-year survey show of her work. And in the catalogue essay to a May 2022 show curated by Tamar Hovsepian and myself titled “The Future of Things Passed,” I also noted—in yet another nod to the quixotic or uncanny in her work—that the past and the future “seamlessly coexist…in canvases (which) possess a boldness at once intellectually intriguing and viscerally arresting.” In “Mary’s Chairs,” (2022) Simonian places chairs by New York artist Mary Heilman in a Cambodian cityscape taken several years later, while a series of pointillist people recall 17th and 18th century chinoiserie. In “Studio Ballou,” (2019) she paints a Mike Ballou sculpture resting on a three-legged chair that stands atop a large rug, as a river of colors flows by in an empty room.

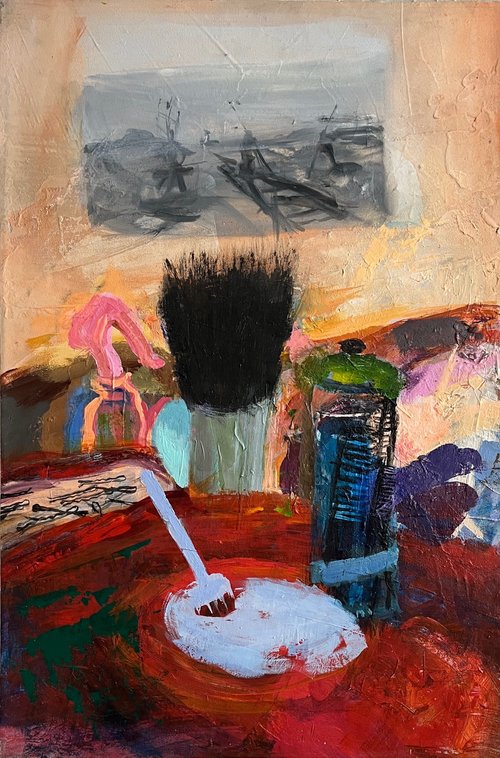

Marysia Beauty Salon, 30×20 inches, acrylic on canvas, 2024.

****

But back to her upcoming solo exhibition at JJ Murphy Gallery, which runs from May 21 to June 21, 2025. As my studio visit draws to an end, Simonian proudly shows me “Marysia Beauty Salon,” (2024) a tantalizingly blurry depiction of the inside of a beauty shop. A large grey rectangle in the back, ostensibly a painting hanging on the wall, represents another indeterminate scene within it. Then comes “Bobby Pins of Manhattan,” (2024) where she highlights the eerie quality of an otherwise common everyday object, another of the random objets trouvés or found items that the artist is fond of elevating. Gallery owner JJ Murphy corroborates my sense of the surprise or perhaps the unheimlich in her work: “I find it interesting how Simonian employs careful framing to create meaning in her work,” he says. But then he points out an element that I had not noticed before: “I think it’s possible, for instance, to view several of her landscape paintings as subtle political allegories. In ‘Greener Pastures’ (2025), for example, the shimmering image of the Statue of Liberty appears to be a mirage.” Inspired by the depth of a ship in a film about Louise Bourgeois, the work wryly comments on the current political scene in America. Still, the fact that the Statue of Liberty is depicted in shiny neon yellow perhaps hints that liberty may still come through and win the day. Commenting on her canvas: “Resting on Her Side” (2024), based on a Katherine Bradford sculpture, Murphy adds: “It depicts a rocky terrain and the bleak spectacle of a capsized ship in the water, which also has some political overtones.”

Bobbie Pins of Manhattan, 20×16 inches, acrylic on canvas, 2023-2024.

As I ponder these words, I recall the last piece that Simonian pulls out, a painting of a vase titled “Limoges Tankard,” (2025). A recurring motif in her work, here the vase is surrounded by luscious purple grapes hanging at the side. The vase as human figure, as muse, which harks back to a site-specific drywall installation that Simonian constructed in San Diego in the early 1980s. The wall was black with a spinning white vase painted on it. Local graffiti artists, whom Simonian expected might playfully tag the work, instead destroyed it. Simonian then rebuilt it from its shattered state. The experience reinforced her appreciation for the vulnerability of making public art and the necessity of reacting to unanticipated responses to her work. This leads to a fascinating avowal by Simonian, namely that she is quite conscious that she invariably loses control of her creations, and that she derives pleasure from this abandon: “I’m not a control freak,” she states tersely. In “Star Quality,” (2023) another slightly eerie image emerges: the neck dummies in jewelry stores that are stand-ins for humans. These pieces, too, are political in a broader sense, in what they say about how we see the world, and how everyday objects can morph according to context—innocent at one moment, pulsing with meaning at another. Simonian avers: “I see all these things: the faceless jewelry dummies, banquet tables and other locations like theatrical stage sets. As an artist, I am seduced into seeing the story or place within them.” For the viewer seeking a transformative experience or the critic eagerly trying to get inside her mind’s eye, this also represents a seductive proposition.

Learn more about Judith Simonian: www.judithsimonian.com