After spending a month in Berlin as part of the 100+10: Armenian Allegories festival—and visiting dozens of exhibitions, performances, and film screenings—I’m eager to draw some broad comparisons with the Armenian art scene. Of course, such a comparison is neither fair nor entirely valid. Berlin is an undisputed art capital of the world and, crucially, one of the best-funded. The sheer scale of investment in the cultural sector is palpable: it radiates from every corner of the city’s beautifully designed and meticulously maintained spaces, and from the exceptional quality of production visible even in the smallest exhibition or stage play. One could argue that Berlin has built its contemporary identity around its cultural infrastructure, which is seamlessly woven into the routines and rhythms of daily life.

This stands in stark contrast to Armenian realities, where the production and consumption of art are pedantically and delusionally presented as an escapist “alternative” to everyday social life. Just witness the absurd spectacle of sweaty bodies rushing through the cramped, under-resourced rooms of Armenian museums during the free but exhausting “Museum Night”—an event that feels more like an endurance test than a celebration of culture. In Berlin, by contrast, one can experience almost any art event or venue in relative tranquillity and comfort. This is because engaging with art is a natural, habitual part of life, instilled from kindergarten as a key element of democratic participation and civic responsibility.

For Berliners, encounters with art are not merely about aesthetic pleasure; they are a means of building awareness and fostering political engagement with both local and global contexts. This is why what Pierre Bourdieu called cultural capital is so tangible here—as a resource that shapes everyday interactions, social etiquette, and networks. It is a form of wealth that helps Berliners stay in tune with one another and with their environment, despite the city’s remarkable diversity of cultural, religious, ethnic, and sexual identities. It’s the kind of openness and tolerance that visitors from more conservative regions (as well as local neo-fascist or far-right groups) often misread as complacency or evidence of “weakened” European morals. But what I saw was power—in the most positive, socially egalitarian sense: the kind that creates space for critical self-awareness, even self-deprecation, while strengthening the empathetic ties that bind individuals to place and civic life.

It’s the kind of power I long to see in Armenia—when the enormous, and largely untapped, potential of our cultural ecosystem is finally recognized and made a political priority.

EXHIBITIONS

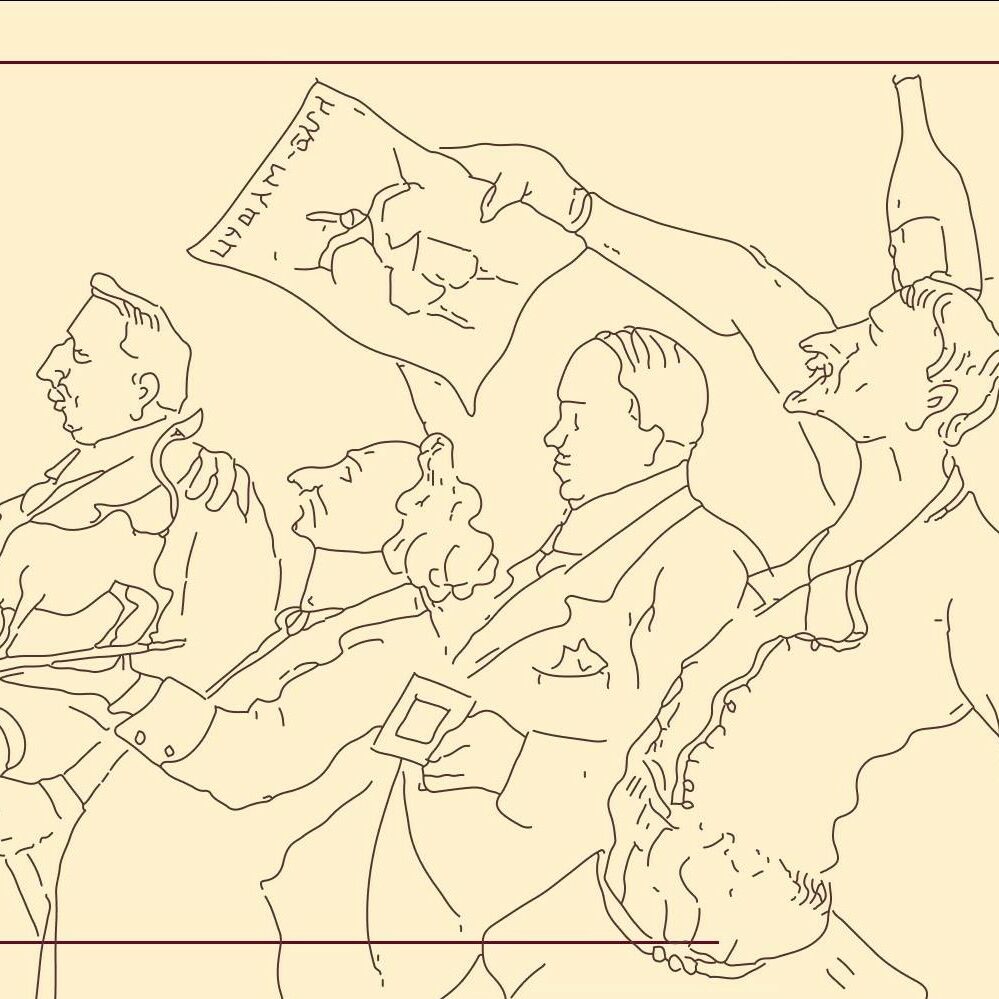

One doesn’t have to look to Europe to find art that served as a tool for self-reflection in its time. More than a century ago, in still-colonized yet cosmopolitan Tbilisi, a young man from a poor Armenian family became infatuated with painting and discovered his prodigious talent for capturing rapid-fire, astonishingly visceral impressions of his environment with nothing more than pencil and paper. Lacking formal training or real career prospects, Vano Khojabekyan spent most of his life working as a hotel doorman, watching from the sidelines as Tbilisi’s multicultural parade of fading urban rituals, traditions, and parochial customs was steadily transformed by the onset of modernity.

The gentle nostalgia that runs through Khojabekyan’s hundreds of sketches never overshadows the sharp wit and satirical edge with which he portrayed the social inequalities, provincialism, and strange decadence of this disappearing world. It’s a wonderfully balanced, self-critical vision that comes vividly alive in the exhibition Through a Documentary Eye: Vano Khojabekyan – 150, fittingly organized by the Home Museum of Giotto—another “outsider” Tiflisian artist deeply influenced by Khojabekyan’s singular artistic commitment and humanism.

Curators Arpine Saribekyan and Seda Khanjyan have given the show a straightforward yet effective structure, arranging it around the key themes of Khojabekyan’s oeuvre. It offers an invaluable opportunity not only to view these rarely exhibited, fragile works on paper, but also to re-evaluate the analytical and socially engaged spirit of pre-Soviet modern Armenian art.

Exhibition: “Through the Documentary Eye: Vano Khojabekyan – 150”

Where: National Gallery of Armenia

Republic Square, Yerevan

Dates: Open from May 17

•

The 1960s was a particularly fruitful period for graphic arts in Armenia, as the medium took on a renewed social role as a taste-shaping force. Among the notable graphic artists to emerge in that decade was Henrik Mamyan, who is receiving his first retrospective exhibition this month at the National Gallery of Armenia. From the outset of his career, Mamyan received countless commissions for book, magazine, and poster illustrations that adorned the most widely circulated Armenian periodicals and the best-known classics of Armenian literature.

Far from being a mere servant to the literary text, Mamyan’s illustrations helped shape the visual imagination of successive generations in Armenia. Working largely in print techniques such as drypoint, linocut, and woodcut, he developed a highly recognizable style—marked by the stylish sinuousness of his lines, cinematic dynamism, and striking emotional expressiveness. The melodramatic power of his art reached its peak in the stunning red-and-black illustrations for Yeghishe Charents’s The Mad Mob—unquestionably one of the great monuments of 20th-century Armenian graphic art.

While the earnestness and classicist bent of Mamyan’s vision belong distinctly to a bygone era, his extraordinary mastery and attention to execution stand as a poignant reminder of the rich, now largely lost, culture of Armenian book art.

Exhibition: “Breathing Papers”, Henrik Mamyan

Where: National Gallery of Armenia

Republic Square, Yerevan

Dates: Open from June 20

•

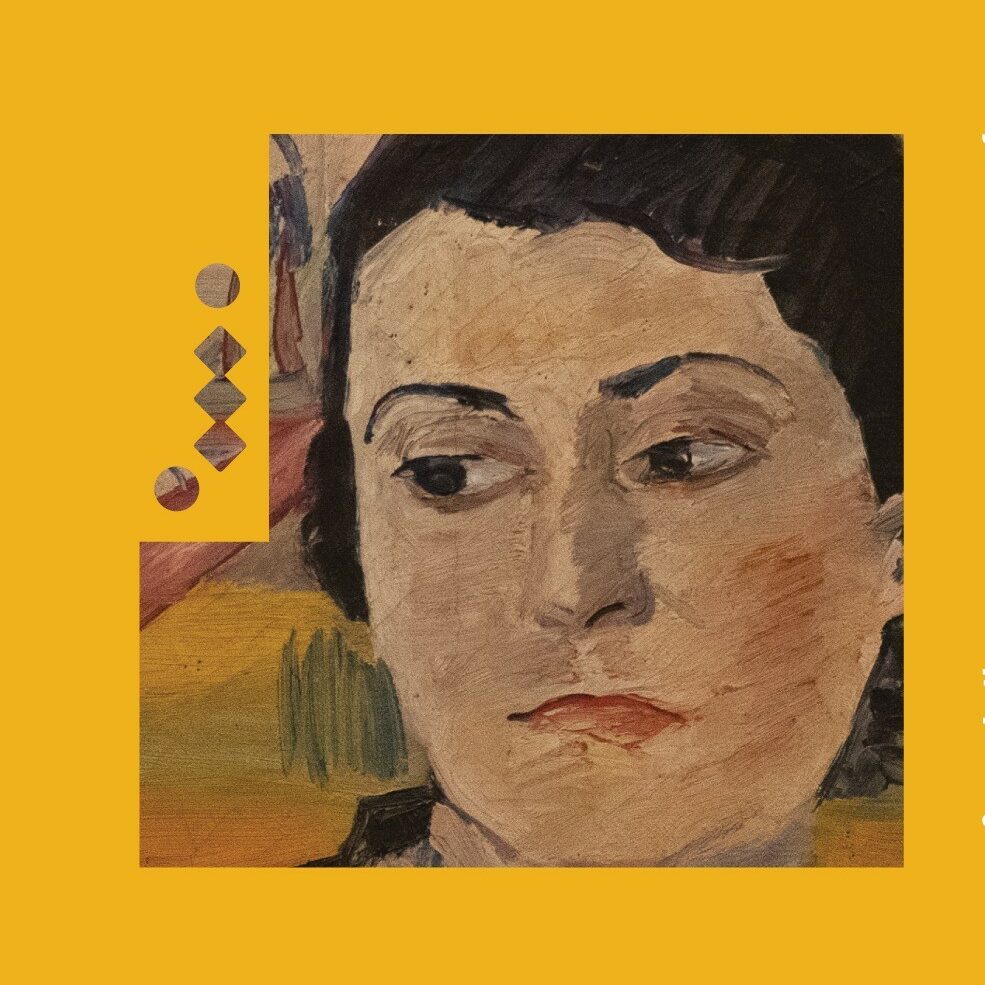

The Literature and Arts Museum is offering visitors a welcome surprise from perhaps the most familiar of all Armenian artists—Martiros Saryan. As one of the largest repositories of modern Armenian culture, the museum holds a vast collection of Armenian visual art, much of which rarely sees the light of day due to its chronic lack of exhibition space. Following the relocation of the Marcos Grigoryan Museum of the Orient to new premises, the museum has finally gained room for temporary exhibitions.

While the choice of a marquee name like Saryan for this inaugural event may be predictable, the exhibition Familiar and Unfamiliar Faces provides a rare opportunity to view the museum’s lesser-seen holdings of the artist’s work. The majority of the 60 or so works on display are portraits of cultural figures that Saryan painted and drew over his remarkable seven-decade career. This focus invites viewers to reassess Saryan from a less-explored angle—not only as the artist who helped forge a distinctly “Armenian” syntax of modernist art, but also as a chronicler of his time, whose portraits played a vital role in shaping the iconography of Armenian high modernity.

Alongside widely known works, such as the stunning 1923 portrait of Yeghishe Charents, visitors will encounter numerous depictions of lesser-known or long-forgotten figures who deserve to be rediscovered—just like Saryan’s significant yet often overlooked role as a socially and politically engaged artist.

Exhibition: “Martiros Sarian: Familiar and Unfamiliar Faces”

Where: Museum of Literature

and Art

1 Aram Street, Yerevan

Dates: June 10-July 10

•

An artist long overdue for proper recognition in his homeland has made a quiet yet striking reappearance in the library of the Cafesjian Centre for the Arts. The fact that Zadik Zadikian’s name resonates only within a narrow circle of art professionals in Armenia speaks volumes about the deep disconnect between the cultural spheres of the country and its diaspora.

Born in 1948 in Yerevan, Zadikian showed prodigious talent as a sculptor from a young age, coupled with an uncompromising dedication to creative freedom. At just 19, the athletic artist risked his life escaping the USSR—crossing the Arax River in winter, under border guard gunfire, into Turkey. After reaching San Francisco in 1969, Zadikian swiftly established himself on the contemporary art scene, first as an assistant to star artists like Benjamin Bufano and Richard Serra, and soon after as an audacious newcomer striving to carve out his own niche in New York’s fiercely competitive art world.

Since the late 1970s, Zadikian has focused on large-scale, often immersive installations. Entirely gilded, these shimmering structures dissolve the boundaries between sculpture, design, and architecture with the kind of overwhelming aplomb that typifies one of postmodern art’s major stylistic directions: Excessivism. Yet despite surface parallels with postmodernism’s ironic embrace of spectacle and consumerism, Zadikian’s use of gold is not a commentary on materialism. Rather, it seeks to reassert the ideal of beauty and the spiritual transcendence of art.

The installation at Cafesjian—a reworking of his earlier piece Foreigners—takes on an unexpectedly political dimension in light of the current quasi-dictatorial, far-right climate in the United States. It also resonates powerfully within the Armenian context, with its rapidly evolving social fabric and long history of xenophobia. Oscillating between pure abstraction and figurative forms, the work exerts a mesmerizing, almost magical effect, inviting viewers to contemplate the sublime and the transformative spiritual forces at play.

Exhibition: “RETURN”, Zadik Zadikian

Where: Cafesjian Center

for the Arts

10 Tamanyan Street, Yerevan

Dates: Open from May 6

•

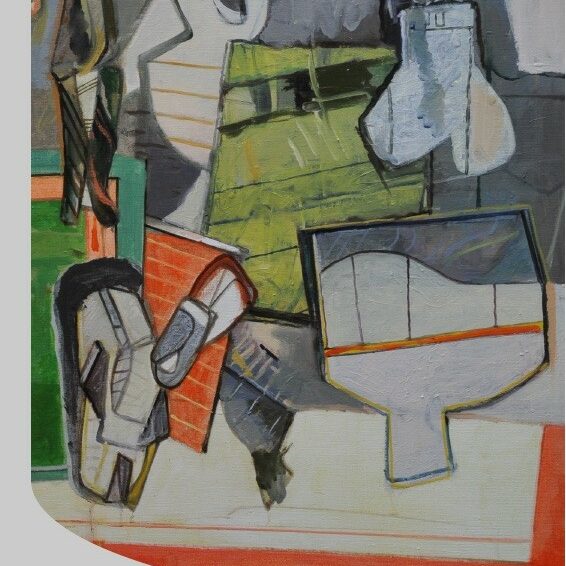

Looking at the Armenian art scene, one might think the crisis of modernist art in the 1970s never happened. Many older, established, and even emerging artists continue to work in traditional media, with a sustained focus on the formal aspects of visual art. Painter Ara Haytayan has always remained steadfast in his commitment to modernism, freely moving between figurative and abstract modes, often blending conflicting stylistic tendencies—think Arshile Gorky and Roberto Matta by way of Rauschenberg, or Keith Haring.

The artistic challenges Haytayan poses in his new solo show at HayArt Centre are age-old: How can one capture the hidden and intangible essence of the natural world and its artificial counterparts? How can the transformative power of art unlock new ways of seeing? In this sense, Haytayan treads an old Roman road, dusting off corners that still have the power to seduce the imagination, if not always to surprise the eye.

Exhibition: “Geography of Transformation”, Ara Haytayan

Where: HayArt Center

7a Mashtots Str., Yerevan

Dates: May 30-July 30

•

On a more contemporary note, a small but noteworthy project-based exhibition is currently on view at the Jermuk branch of the National Gallery of Armenia. Organized by the ToC non-profit, the show features the work of printmaker Sofi Musoyan, sculptor Manvel Matevosyan, and photographer Armen Ter-Mkrtchyan, who were invited to explore and engage with Jermuk’s abandoned Palace of Culture—a remarkable example of late-modernist Soviet-Armenian architecture that has become a dramatic ruin after decades of neglect and vandalism.

Notably, the project’s organizers emphasize the significance of the site in its current state—not as something to be mourned or revived, but as a space that invites philosophical reflection and imaginative engagement with the recent past. While the melancholic “archaeology” of the site leads to works that tread familiar ground within the genre of so-called “aftermath” art, this exhibition offers a compelling example of how artistic initiatives can generate fresh ideas and meanings from dysfunctional traces of history—a process of particular urgency in regional centers across Armenia.

Exhibition: “After Silence”, Multidiciplinary Exhibition

Where: Jermuk Art Gallery

1 Charents Str., Jermuk

Dates: June 14-July 14

•

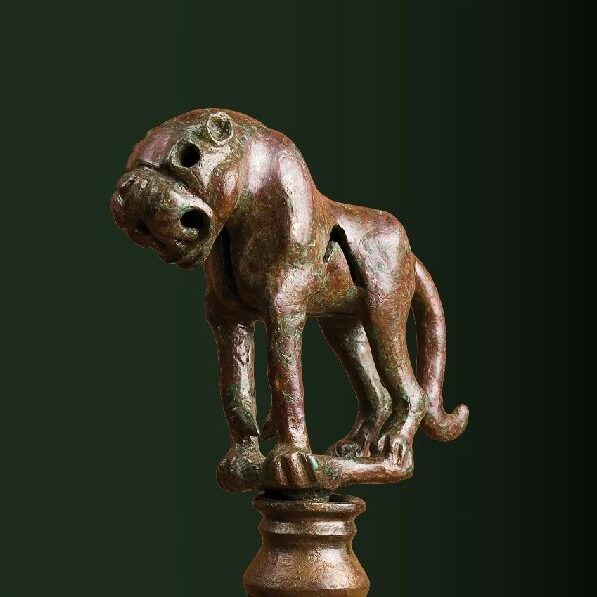

If you lean toward the deeper layers of history, then a new show at the History Museum of Armenia offers a time trip from Stone to Iron ages. The twist here is that this journey also takes the viewer into the Netherlands. Better known for its Baroque art and Van Gogh, the Dutch lowlands have been a civilizational hotspot since ancient times. The show In the Parallels of the Ancient World—a very welcome product of an inter-museum exchange between Yerevan and Amsterdam—presents a unique chance to encounter the prehistoric art and culture of Dutch ancestry. Though intimate in scale, the less than two dozen artefacts presented here provide some tantalizing insights into the fascinating cultural parallels between ancient cultures across vast geographic divides.

Exhibition: “In the Parallels of Ancient World: Armenia – Netherlands”, Joint Exhibition

Where: History Museum of Armenia

Republic Square, Yerevan

Dates: June 19-July 3

•

Sometimes serious museums feel compelled to stage esoteric exhibitions that prompt the inevitable question: Oh God, why? More often than not, these are little more than marketing ploys—curiosity-stirring showcases designed to lure visitors with the promise of idiosyncratic bric-a-brac. Yet beyond the surface allure of historical eccentricity, such projects often offer little in the way of meaningful insight.

The Literature and Arts Museum in Yerevan has no shortage of curiosities, gathered over the past century as memento mori of our cultural icons. Its vast collection of relics includes objects that have passed through the hands, heads, or other body parts of Armenia’s cultural patriarchs—everything from pipes, hats, and glasses to gloves, walking sticks, and even underwear.

A new exhibition brings together around 60 watches once carried by a constellation of Armenian luminaries, including Mikael Nalbandyan, Hovhannes Tumanyan, Martiros Saryan, Aram Khachaturyan, and others. There is, to be sure, a mild curiosity in seeing what types of pocket and wrist watches these great writers, composers, and artists owned. But to what end? The exhibition aspires to little more than venerating these sacrosanct souvenirs. It makes no attempt to explore the sociological, philosophical, or cultural questions these objects might (or might not) raise about their owners and the conditions in which they lived and worked.

It’s an all-too-familiar scenario in Armenian museums—one that would benefit from looking outward, toward international models that engage scholars, curators, artists, and the public in rethinking how to present such miscellaneous collections with substance and relevance.

Exhibition: “Arrows of Memory”

Where: Museum of Literature

and Art

1 Aram Street, Yerevan

Dates: June 14-June 28

•

FILMS

Art has a strange and uncanny ability to become sharply relevant, sometimes decades or even centuries after it is created. In the case of truly great artists, their work never seems to lose its vitality or pertinence, no matter how radically humanity shifts its course. Charlie Chaplin is unquestionably one of these artists. On the 100th anniversary of his majestic masterpiece The Gold Rush, Kazm NGO is marking the occasion with simultaneous screenings of the recently restored film in five cities across Armenia: Yerevan, Gyumri, Vanadzor, Kapan and Kajaran.

As delightful, funny, and endearing as The Gold Rush is in its slapstick comedy, its deeper significance lies in Chaplin’s subtle shift toward more political territory—a direction clearly heralded by this film. On the surface, it is a comedic adventure about the beloved Tramp’s hapless efforts to strike it rich by finding a “pot” of gold in the mines. But this flimsy scenario serves as a pretext for Chaplin to peel back the layers of the American collective psyche and expose the profound malaise at the heart of capitalism and the destructive pursuit of wealth.

Many of the film’s most iconic scenes—such as the Tramp cooking and eating his shoes for lunch—have long since become cornerstones of global visual culture. The tragedy is that the allegorical resonances of The Gold Rush continue to echo with undiminished power in an age when the future of entire nations hinges on their ability to supply rare earth minerals to corporate overlords.

Screenings: “The Gold Rush”

Where: Moscow Cinema (Yerevan), Cinema Olimpic (Gyumri), KinoLori (Vanadzor), S’Unique cinema (Kapan), Kajaran Cinema (Kajaran)

Dates: June 26, 7 p.m.