Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

In today’s pessimistic reality, few people remember the smiles and celebrations of millions of Armenians around the world, who heralded the change in government in the spring of 2018. After more than two decades of indifference and a sense of powerlessness, the citizens of the Republic of Armenia and many Armenians worldwide finally felt responsible for the formation of their own government in Armenia. It was a joint, nationwide effort.

The afterglow of the proclaimed Velvet Revolution that culminated in Serzh Sargsyan’s resignation united Armenians, filled them with positive expectations, and granted Armenia an “entrance ticket” to becoming a more sovereign and independent state.

Given that most of our neighbours in the region viewed democratization and human rights as instruments being used against their own interests, it was in the common perceived interest for democracy to fail rather than succeed. As a result, Armenia’s bid to pursue an independent and sovereign policy as a democracy was perceived to have a geopolitical context. The danger was in not seeing that reality, not evaluating it, and not recalculating domestic, foreign and security policy accordingly.

Now that more than three years have passed, it is time to look retrospectively and pursue the answers to a number of questions:

- Has democracy succeeded in Armenia so far?

- What opportunities and threats did democracy—gained through the revolution—hold?

- How have we managed these opportunities and threats?

- What damage have we suffered as a result of the mismanagement of those opportunities and threats? Could the better governance of those have prevented the war?

The Advance and Retreat of Democracy

At the end of 2018, The Economist named Armenia “Country of the Year” for its advancement of democracy. The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) ranked Armenia among the countries that “made the most progress” that year. Armenia’s position improved from 112th to 103rd out of 167 countries, up to 86th in 2019.

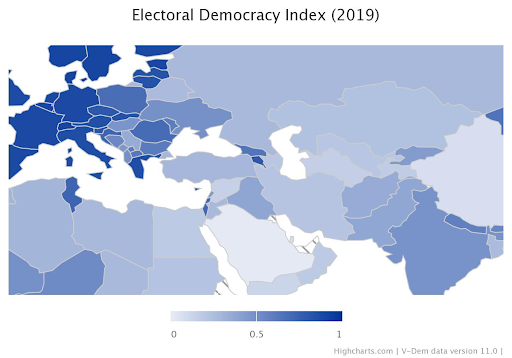

V-Dem Electoral Democracy Index 2019

Among the 29 transition countries from Central Europe to Central Asia rated by Freedom House, Armenia (the only country on the list with a “semi-consolidated authoritarian regime”) [2] improved its rating, first from 2.57 to 2.93 in 2019, then by 3.00 in 2020, occupying the 21st position and almost reaching the status of a country with a “Transitional or Hybrid Regime”. [3]

After a gruelling 2020, however, just two years after the revolution, Armenia’s progress was halted and a distinct retreat took its place. This trend was reflected across the board:

- EIU Democracy Index: retreating from 86th to 89th position (among 167 countries);

- V-Dem Electoral Democracy Index: retreating from 38th to 39th position (among 179 countries);

- V-Dem Deliberative Democracy Index: retreating from 33rd to 38th position (among 179 countries); [4]

- V-Dem Participatory Democracy Index: retreating from 37th to 46th position (among 179 countries); and [5]

- Freedom House Nations in Transit: retreating by 0.04 points (preserving the 21st position).[4]

The 2020 Artsakh War and the restrictions imposed by martial law for more than two months undoubtedly had a negative impact on the state of democracy, but to understand the picture at a deeper level, one must look at how the opportunities and threats associated with democracy have been managed.

The Opportunities of Democracy

The greatest opportunity provided by the progress of democracy was, perhaps, the prospect of the creation of inclusive political and economic institutions. Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, who have made the greatest contributions to the study of the role of institutions, believe that the establishment of such institutions is a key precondition for a state to prosper. According to the theory in their well-known book, Why Nations Fail, inclusive institutions enable wide democratic participation, prevent resources from being overexploited and individual people from enriching themselves without benefitting the rest of society. The second precondition is the existence of a viable government with undisputed authority, widely accepted by the people, with an agenda aimed at creating inclusive institutions.

In post-revolutionary Armenia, both preconditions were met. The majority of Armenians united around the newly-elected Prime Minister and the government and were ready to engage in hands-on participation. The Prime Minister, in turn, on behalf of the Government, promised to dismantle the previously built extractive institutions (institutions that marginalize or undermine the public interest or public good) and replace them with new “inclusive” ones.

A number of extractive institutions were indeed dismantled, in particular the institutions of systemic corruption, mass electoral bribery and economic (imports related) monopolies. However, a larger number of extractive institutions continued to operate and, in some cases, even emerged, compromising the foundations of statehood. Such institutions include systemic nepotism, conformity and opportunism in public administration, a biased judiciary and law enforcement, flawed habits and culture in interpersonal and public relations (hate speech, intolerance, aggression, hollow patriotism, poor work culture, poor debate culture, environmental negligence, etc.).

On creating inclusive institutions, the re-launch of the institution of free and independent elections can be considered a success: two national and a number of local elections were held in a free and competitive manner. Undoubtedly, this is an institution of key importance, which, however, is a necessary but not sufficient precondition for strengthening the state and boosting the economy.

A number of other important inclusive institutions have not been introduced to this day, adding to our rich database of lost opportunities. In particular, taking into account the situational management over our 30 years of independence, one of the most demanded inclusive institutions was (and still is) a system of strategic management and decision-making using the full intellectual and expert potential of the Armenian people. The best implementation of the to-be Prime Minister’s early pledge to share the power with the people would have been the development of a national-wide strategy with the inclusion of the professional and expert community in the deliberation process —systematically and proactively involving them at an advisory level in the process of problem-solving and risk analysis, as well as in the process of policy and strategic solutions crafting.

Such an approach would have made it possible to unleash and fully realize the potential of democracy and inclusive institutions in the decision-making of national or state importance, as opposed to limiting the participation of citizens to only emotionally driven general elections.[6]

The digital technologies of the 21st century allow the creation of an inclusive strategic decision-making system (“living strategy”) unparalleled in the past. Building such a system to serve the national interests can be a defining innovation in the development of deliberative and participatory (direct) democracy of the new age. The foundations and architecture of such a system were created in 2019 and 2020, however, not implemented to date, leaving the perception of the national strategy to mere populist and wishful slogans and narratives, and leaving the collaboration between the government, the professional community and the people at the level of the “e-draft” website (reactive feedback to draft regulations) and traditional public consultations/hearings.

The Prime Minister’s call in 2018, which was to become another important inclusive institution—a system of attracting professional and motivated talents to the state system—despite the existing preconditions and expectations, was never introduced. Efforts to establish the institutional approach finally faded in 2020, giving way to traditional nepotism, which was back in action as a rule, making the competent appointments mere exceptions.

Another missed opportunity was that of carrying out a behavioral revolution—the need to reshape our national traits and values. Where it was necessary to quickly change public attitudes and behavior through sound compulsory means (such as not littering or compromising the environment or ensuring traffic and vehicular safety), actions were limited to mere verbal interventions and half-hearted initiatives. Meanwhile, in other cases, where leading by example and setting a good role model are far more effective than punitive measures, we see hard-coded approaches being undertaken such as the passage of legislation criminalizing hate speech and insults.

After all, what are our national values upon which we will be able to not only preserve what we have, but also build upon and achieve national strategic goals? A properly conducted public discourse on that matter could have secured a much-needed general public consensus, an opportunity granted by democracy.

Missed opportunities include timely and effective judicial and law enforcement reforms; the development of a geostrategic analysis-based new foreign policy doctrine and a national security strategy (based on a comprehensive assessment of geopolitical risks and opportunities); the development of contingency plans for the population, economy and public administration (based on the analysis of the major what-could-go-wrongs such as war, emergencies and natural disasters); the implementation of transitional justice; and many other belated institutional solutions, the need for which stems from our strategic goals.

The Threats of Democracy

The “entrance ticket” to becoming a more sovereign and independent state powered by democracy came with a “best before” date and price. It was clear from the start that the level of trust and expectations toward the newly-elected Prime Minister and government would eventually subside from the euphoric heights of 2018. Therefore, the lion’s share of institutional transformations and reforms needed to be carried out during the first two or so years. The “golden rule” of reforms is “strike while the iron is hot.” The danger was in missing the right moment, delaying the creation of inclusive institutions or deviating from the transformational path.

The other danger was the price of the “entrance ticket”. Although the revolution of 2018 had no explicit geopolitical overtones, the result of the revolution did send a message to neighboring authoritarians (see Figure 1).

Another danger that threatens democracy not only in Armenia, but also in a number of established Western countries, is the unhealthy transformation of democracy into an ochlocracy, driven by emotional appeals and attachments impairing public reasoning and deliberation. The threat is tangible especially for countries and nations undergoing transitional and crisis periods, and therefore poses a special danger for Armenia. With low levels of civic capital and public discourse, even with the fairest and freest elections, democracy can degrade and metamorphose into a mere tool for winning votes of the emotionally driven masses through simplified political discourse.

The Results of Mismanaging the Opportunities and Threats

In the absence of a functional inclusive strategic management system, the government has continued to underuse the intellectual potential of the expert community and public at large, limiting and undermining itself in terms of institutional capacity. As a result, government-developed policy measures and institutional solutions often miscalculate Armenia’s real challenges, risks and problems.

Numerous institutional reforms and/or transformational initiatives have been sluggish or handicapped due to the lack of talent in the public administration – talent to be systematically engaged based on merit, professional integrity and a sense of mission. The predominant approach of politically motivated decisions with respect to public administration human resources acquisition and development, in essence, continued the vicious tradition of previous decades, resulting in an extremely ineffective and inefficient public administration system. Officials and public servants, as a rule, act only in case of explicit instructions received from their supervisors. The malfunctioning of public governance was further exacerbated by a low and deteriorating level of execution discipline. The institutional capacity of the government, which in reality could have been multiplied due to the opportunities posed by the democratic advancement, was in fact further impaired, whereby the successful ad-hoc appointments could not justify or compensate for the overall damage caused by the predominant approach.

In the absence of the critical reassessment of the values as a result of the revolution, society was unprepared to absorb the higher level of democracy and freedoms. Suddenly-acquired additional freedoms and rights (for example, freedom of speech) began to be widely misused to the detriment of common good and public interest. Intolerance and insults became widespread, blaming and rejecting was increasingly preferred to listening to and cooperating with each other, and making hasty and superficial conclusions were increasingly preferred to deliberating and asking deep-rooted questions. What is especially sorrowful is that this behaviour was embraced by many opinion makers and “intelligentsia”. As a result, due to the lack of leadership in this respect, democracy, by virtue of greater liberties and freedoms, in fact, contributed to the division and fragmentation within society, which in turn contributed to the undermining of the foundations of our state and statehood.

As opportunities were not realized, the risks and threats, being the opposite side of the coin, were better positioned to be realized.

As a result of not utilizing the window of opportunities within the two years, we have shown our lack of will and consistency not only to ourselves, but also to the outside world – our allies, partners and adversaries. They, unlike us, used all the opportunities we provided them with. In particular, we gave our opponents the opportunity to attack us, and our allies and partners the opportunity to refrain from helping us sufficiently. This thesis is based on the following logic.

If, within two years following the revolution, we had consistently and unwaveringly built inclusive institutions and had undertaken the “values transformation”, we would have had the following results that would have arguably prevented the war:

- By assuming the role of a new age pioneer in the field of deliberative and participatory (direct) democracy and creating a new value for the world, Armenia would have deserved a much higher appreciation from the international community.

- The introduction of an inclusive strategic decision-making system would have, both, “insured” the government against the negligence of the real risks from our adversaries, and “not seeing” insufficient support from the allies and partners, as well as, allowed us to work with the expert community to develop strategic policy solutions to deter adversaries and ensure the necessary mutual assistance with partners (for example, new foreign policy doctrine, national security strategy based on risk and opportunity assessment, war risk management and rapid response plans, etc.).

- State and public managers endowed with professional merits and integrity, and guided by the sense of mission, would have served the national interest with much greater responsibility, effectiveness and efficiency, and would have carried out the necessary reforms and transformations with much greater speed and effect.

- A people firmly united around the values, immune to division, would have significantly increased their collective effectiveness, would have been perceived as an active and effective guarantor of the Armenian state and statehood, which would have kept the foreign players away from the temptation to expand their influence and expand territories at the expense of Armenia’s sovereignty.

Why we did not have the results we could have had, and what the main reasons for the mismanagement of the opportunities and threats that emerged as a result of the revolution and democratization were, deserves additional scrutiny and analysis.

One thing is certain: we can no longer continue in the same way.