Take an evening stroll through downtown Yerevan and you will hear live jazz tunes coming from neatly decorated cafes and jazz clubs. It seems that jazz music has become woven into the city and its character. But it wasn’t always that way. Jazz and Armenia have a complicated history.

Jazz and the Soviet Union

The Communist Party’s attitude toward jazz in the Soviet Union alternated between hot and cold, going from prohibition to state sponsorship and then back to censorship. The emergence of jazz in Russia and the Soviet Union is tied to Valentin Parnakh, a poet, musician and choreographer, whose first exposure to the genre was in France in 1921. After hearing Louis Mitchell’s Jazz Kings perform at a Parisian café, Parnakh was fascinated and planned to start the first jazz band in Russia.

Returning to Moscow in 1922, Parnakh bought all the necessary instruments and brought together a group of young musicians under the name The First RSFSR Eccentric Orchestra: Valentin Parnakh’s Jazz Band (Первый в РСФСР эксцентрический оркестр – джаз-банд Валентина Парнаха). Although Parnakh’s music differed from what jazz sounded like in the West, focusing heavily on dancing and theatrical shows, the Soviet public gradually warmed to the new style, opening new possibilities for it to develop further. Parnakh’s initiative also instigated performances by musicians from the United States, including Sam Wooding and Benny Peyton, who visited Moscow in 1925.

In 1923, the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians (RAPM) was founded, which soon took the responsibility of organizing Soviet musical life. RAPM members advocated for songs inspired by folk music and characterized by proletarian elements. They were in an ideological fight against the Association for Contemporary Music, which was more accepting of Western music. The RAPM saw jazz as a threat to Soviet cultural life and values. It criticized essential characteristics of jazz, like syncopation and minor sixth and seventh chords. The RAPM took measures to prevent the popularization of jazz. By 1928, importing foreign records was banned, public dance clubs were patrolled by Komsomol members and lectures were organized to help propagate proletarian music.

The RAPM wasn’t alone in the fight against jazz: many intellectuals, including Anatoly Lunacharsky and Maksim Gorky publicly condemned it. Lunacharsky, who had previously supported the professionalization of jazz and even sent Leopold Teplicky to the United States to study it, later came to consider jazz to be “sonic idiocy in the bourgeois-capitalist world.”[1] Similarly, Maksim Gorky didn’t miss an opportunity to attack the genre. In 1928, Gorky wrote an article entitled The Music of the Gross, where he drew parallels between jazz and eroticism:

The hard knock of an idiotic hammer penetrates the utter stillness. One, two, three, ten, twenty strikes, and afterwards a wild whistling and squeaking as if a ball of mud was falling into clear water; then follows a rattling, howling and screaming like the clamor of a metal pig, the cry of a donkey or the amorous croaking of a monstrous frog. The offensive chaos of this insanity combines into a pulsing rhythm. Listen to this screaming for only a view minutes, and one involuntarily pictures an orchestra of sexually wound-up madmen, conducted by a Stallion-like creature who is swinging his giant genitals.

(An excerpt from The Music of the Gross, first published in Pravda, April 1928).

Soviet jazz experienced a reprieve in 1932, when the RAPM dissolved. The early 1930s witnessed the rapid spread of the genre, as the relaxing of restrictions coincided with the introduction of new mass media such as radio and records.

However, the dissent over jazz rose back to the surface in November 1936, when two major newspapers, Pravda and Izvestia, engaged in a heated debate about the role of jazz. Everything started with a letter to Izvestia from two classical musicians who expressed their discontent over shrinking employment opportunities for classical musicians as jazz bands took over. Three days later, Pravda published an article entitled “Against Frauds and Saints” in response to Izvestia. The author, Boris Sumiacky, defended jazz claiming that it brought joy to millions of people. The editorial fight between the two newspapers produced a total of 19 articles, the last of which, an editorial by Pravda entitled “А Philistine Blather on the Pages of Izvestia,” accused Izvestia of anti-Soviet propaganda.

Later, the Great Purge of 1936-1938 put jazz in crisis, as all Western elements came under attack. Soviet authorities especially targeted those who had contacts overseas. In 1937, Parnakh was handed a 10-year sentence. The next year, Georgy Landsberg, the leader of the Leningrad radio jazz ensemble, was sent to a workers’ camp. Other jazz musicians like Leonid Utesov and Aleksandr Cvasman, who had better relations with the authorities, were spared. They modified their music to fit the proletarian standards of the time.

The Birth of Professional Jazz in Soviet Armenia

Tsolak Vardazaryan and the Armenian State Jazz Orchestra (Source: ArmJazz75).

The Armenian State Jazz Orchestra, headed by Artemi Ayvazyan and conductor Tsolak Vardazaryan, was formed in 1938. The band quickly became one of the leading jazz orchestras of the USSR. During World War II, Soviet Armenian authorities sent the orchestra to hold concerts for the Red Army. They played in military bases, hospitals, ships and even temporary shelters. As we learn from Armen Tutunjyan’s book “Jazz in Armenia,” the orchestra played both Armenian and foreign pieces. Many years later, a nurse, Lidia Karpovna, would recall her memories of the Armenian jazz orchestra, “I had seen a lot on the battlefield. But I had never before seen joyful soldiers going to the frontline with the orchestra’s Jan Yerevan on their lips.”

Following the war, a complete ban was imposed on jazz music until the death of Stalin in March 1953. Nikita Khruschev’s De-Stalinization[2] policies lifted many restrictions throughout the USSR. The early 1960s, known as the Khrushchev Thaw, saw a significant decline in repression and censorship. However, jazz remained a topic of disagreement throughout the Soviet republics.

In his March 1963 Declaration on Music in Soviet Society, Khruschev assured the public that there would be no bans on any kind of music and that he had no intentions to make his favorite types of music the general norm for everyone. On the other hand, he made reference to jazz, criticizing some forms of it and calling it cacophony.

We are not against all jazz music; there are all kinds of jazz music. Dunaevskii knew how to write good jazz orchestra music. I like some songs performed by the jazz orchestra conducted by Leonid Utesov. But there is also music which makes one feel like vomiting, and causes colic in one’s stomach.

Although jazz was no longer totally banned, there were, however, still some restrictions regarding it. As we learn from Armen Tutunjyan’s (Chicko) memoirs, in the early 1960s, there was no contact with European and American musicians; music students had limited or no access to jazz literature. The primary source of sheet music for Tutunjyan and his peers was the Group of Jazz Explorers (ՋՈՒԽ՝ ջազն ուսումնասիրողների խումբ), whose members imported jazz literature from abroad and translated it from English to Russian.

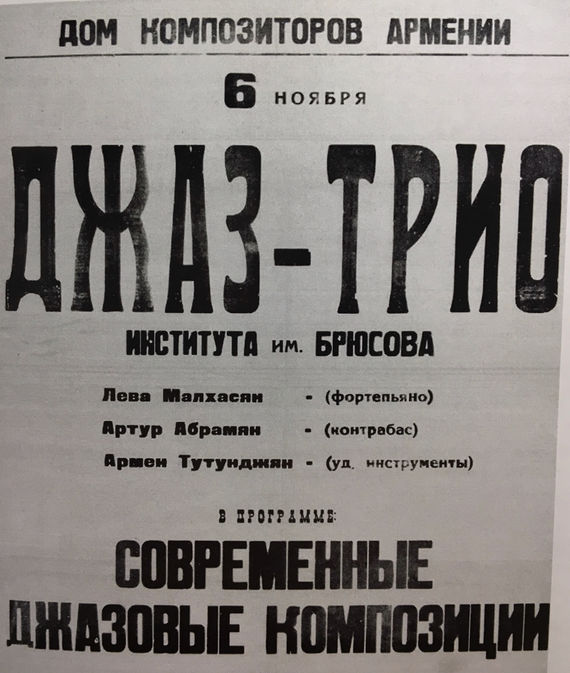

Despite the “Today they’re listening to jazz, tomorrow they’ll betray their homeland” attitude that permeated Soviet society, Armenian jazz had significant developments in the 1960s. According to maestro Levon Malkhasyan, jazzmen were viewed less harshly in Yerevan compared to other Soviet cities. The 1960s marked the beginning of the small band era. In 1963, when Malkhas was still a student at Yerevan Brusov State University, he started the first small jazz band in Yerevan, Levon Malkhasyan Trio, and frequently organized jam sessions. In 1968, Malkhas took a new important step toward the development of jazz in Armenia when he organized the first republican jazz festival.

By the 1970s and 1980s, jazz was in full swing in Armenia. Artists like Malkhas and Chicko traveled throughout the USSR representing Armenia at various jazz festivals. In the spring of 1970, their quartet[3] won the fifth Kubishiev Jazz Festival, where they played jazz standards by George Gershwin as well as Chicko’s original composition, the Armenian Dance. Surprised by the quartet, the head of the jury, Anatoly Krol said that it was his first time meeting jazz enthusiasts from Armenia and that he looked forward to learning more about Armenian jazz.

What Makes Armenian Jazz Armenian?

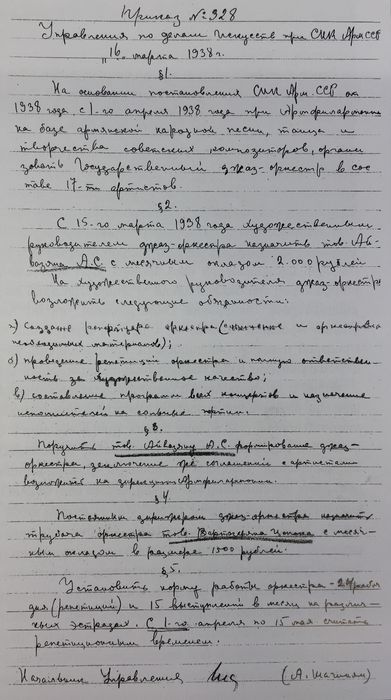

The draft of Order #328 about the formation of a state jazz orchestra in Armenia.

A flyer from a concert organized by Levon Malkhasyan at Brusov University. (Source: Jazz in Armenia by Armen Tutunjyan).

You don’t have to necessarily use folk instruments to prove that you’re playing Armenian jazz. If you were born in Armenia and you possess that national melos, it will inevitably manifest itself in your music.

Levon Malkhasyan (Malkhas)

Perhaps one of the most vivid manifestations of the maestro’s words was the band Time Report, founded by Khachik Sahakyan (piano) and Armen Hyusnunts (saxophone) in the late 1990s. Known for their ethnic jazz music, Time Report transformed Komitas’ pieces and other folk songs into jazz compositions and set Armenian folk music as the base for their original repertoire.

Improvisation is at the core of jazz, as it was in the Armenian ashugh [bard] tradition. In Khachik Sahakyan’s opinion, that has been one of the main factors in the success of jazz in Armenia. “Ashughs were the jazzmen of the past, the eastern version of them. What did they do? They picked up their kamancha or tar and started to compete; improvising, creating a completely new piece right there at that moment. That’s what jazz musicians do today at jam sessions.” Sahakyan believes that improvisation is something that comes from within and perhaps because Armenia and other post-Soviet countries from the region, like Azerbaijan, long had that culture, they were able to understand and feel jazz better than other Soviet republics did.

Although jazz has come a long way, today, pop music remains the mainstream genre in Armenia and much of the world. According to Sahakyan, “It’s easy to listen to temporary pop music. To be able to listen to jazz, one needs to have some preparation. It requires another level of internal intelligence and patience.” He believes in the potential of jazz in Armenia, noting that jazz is facing a decline in Georgia and Azerbaijan, which also once had a developed jazz culture; whereas, in Armenia, the genre is advancing thanks to the efforts of a new generation of independent musicians.

Footnotes:

>Following the war, a complete ban was imposed on jazz music until the death of Stalin in March 1953

Pardon me, this is complete bull. While jazz was frowned upon and subject to certain limitations, there was no single document that would impose a “complete ban” on jazz music. Several notable historians researched the subject, and failed to find any document that “banned jazz.” If such document exists and you have its title, number, and date, please clarify.