Levon Vardanyan, the chief architect of the Old Yerevan Project and his wife Marietta Gasparyan, an architectural historian, were the first employees of the Division of Monument Protection when it was created in the 1970s as part of the Yerevan Municipality. Gasparyan is also the author of “The Architecture of 19th to Early 20th Century Yerevan,” where she explains the architectural value of the buildings of that time. In fact, the theoretical approach to the Old Yerevan Project is based on her research.

“One day the Chief Architect of Yerevan, Jim Torosyan, who was also my thesis advisor called and said that I would be working in this new division since I’m interested in pre-Soviet Yerevan architecture and in designating the ‘black buildings’ built from that era as ‘historic monuments,’’recalls Levon Vardanyan.

During Tsarist Russian rule in Yerevan, buildings were constructed that were known as “black buildings” due to the color of the stones used.

This architecture was considered “Tsarist periphery architecture,” which included several Middle Eastern and Armenian influences. These influences were mainly expressed through the buildings’ inner courtyards.

“Ever since my years at university, I always said that the Tsarist era black buildings were under threat,” Levon Vardanyan recalls. “However, other architects refused to acknowledge them as historic monuments.” While working together in the Division of Monument Protection, Vardanyan and Gasparyan started measuring and categorizing these buildings. Meanwhile, they tried to convince other architects and residents of Yerevan that these buildings needed to be protected and given proper status. However, their pleas fell on deaf ears.

The demolition of these buildings started during the Soviet era, because they were considered to represent bourgeois architecture. However, even after the independence of Armenia, active demolition continued.

At the end of the 1970s, Levon Vardanyan approached Soviet Armenian authorities asking them to allow him to carry out his project of preserving the black buildings located between Amiryan and Aram Streets in the capital city. At the time the historic buildings with their inner courtyards were still intact, however the project was not approved.

In 2005, there was only one building left from that area near the intersection of Aram and Byuzand. However, the government, then led by President Robert Kocharyan, began formulating plans for an urban redevelopment plan in that quarter. “When I realized that the remaining historic architectural monuments were to be demolished as well, I went to see then Chief Architect Samvel Danielyan,” Vardanyan recalls. “I explained to Mr. Danielyan that there were buildings there from the Tsarist era and they should be preserved. The Chief Architect did not listen to me and said that the presidential decree had already been handed down.” Vardanyan then went to see Yervand Zakharyan, the mayor of Yerevan. “I explained to him that those buildings were historic monuments and we shouldn’t touch them. Mr. Zakharyan proceeded with the plan anyways,” Vardanyan says.

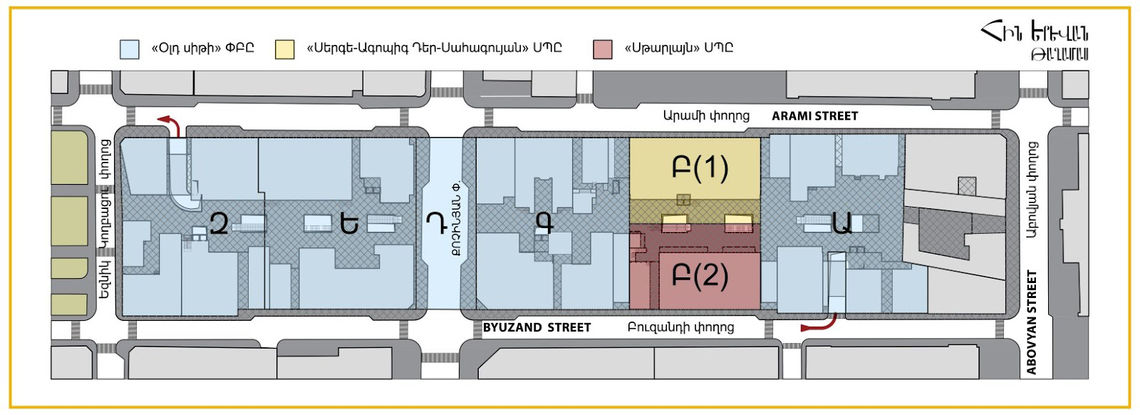

This was how the Old Yerevan Project was born. The area was divided into five lots, put up for auction and sold to three private companies.

While the Old Yerevan Project was approved in 2005, construction only started in 2017. It has been designed to incorporate the neighborhood along Abovyan, Byuzand, Koghbatsi and Aram Streets (altogether 2.2 ha). The Project includes the original residential houses from the 19th and early 20th centuries that are architecturally intact with their inner courtyards and gardens. According to published state data, the project envisions the restoration of the colorful outer brickwork of the buildings from the early 19th century, decorated facades, as well as ornamental wooden or metal balconies.

The Old Yerevan Quarter is going to be non-residential. However, it’s not clear what those 21 reconstructed and restored buildings are going to be used for. One thing is clear: the space is going to serve as an entertainment area with cafes, restaurants, art galleries and museum-shops.

The overall space will have a 7000 square meter glass dome. According to Levon Vardanyan, there are several reasons for this, starting from preserving the harmony of the space to solving issues that may arise from different weather conditions. These historic buildings had stone facades and arched open alleyways. These separated large public spaces from residential homes where you could find gardens and intricate wooden balconies. Since the general appearance of the city has changed to include newly built high rises around that space, the authors intend to build the dome to cut off the Old Yerevan Quarter from that view. They want to create a place where people can stroll and enjoy themselves without having to see modern high rises. Solar panels are to be installed on the sides of the glass dome to provide 24/7 lighting for the space.

The Old Yerevan Quarter has three categories of monuments:

1st Category

Monuments that have been preserved wholly or partially, which are going to be restored according to the project plan.

2nd Category

Monuments that have been dismantled in the past several years, and the stones of which have been kept. They are going to be reconstructed according to the project plan.

3rd Category

Demolished monuments that, according to the project plan, are going to be recreated based on archival and image measurements.