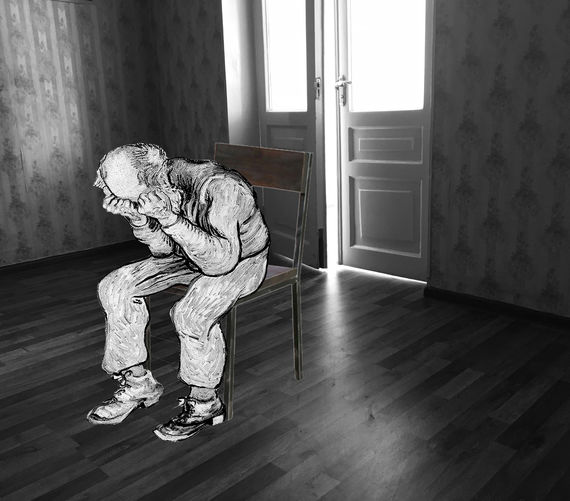

As the door opens, the tepid air seeps into your nostrils. This, of course, could be nothing out of the ordinary until you hear the creaking sound coming from the shabby floors and your eyes adjust to the faint light streaming from dusty light bulbs. A few steps into the building and two elderly men with silver hair and wrinkled faces appear. They position themselves in the corner of the room beside a noisy refrigerator and begin to speak.

This is an ordinary room in a four-story senior’s home in Yerevan. Navasard and Petros are two of the residents along with 223 others. Two different destinies that collided the day they both decided to leave their homes and become permanent residents of the facility. While speaking about their friendship, they compare it to the relationship between brothers; a relationship that is based on trust, love and respect towards each other.

In Armenia, there are five public and eight private old age homes. The Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs is the responsible state body supervising all the public and three of the private centers, which have a contract with the ministry and receive partial funding. According to Anahit Gevorgyan, who heads up the Division for Elderly Issues at the Ministry, 1210 senior citizens live in public and 240 in private old age homes.

There are two types of public old age homes in the country – general and special, the latter being for people with mental disabilities. In public old age homes, senior citizens receive their social security pension, while the center keeps the minimum set old-age pension, which since March 2019 was increased from 16,000 AMD ($33) to 25,500 ($53). Those senior citizens who have mental disabilities and have been identified as not competent to handle money do not directly receive their pension, it is directed to the facility. Private old age homes, according to Gevorgyan, were established and are run by NGOs and predominantly rely on donors for funding. Some require an admittance fee after which payments are on a voluntary basis; some provide unpaid services to those who do not have a family, while paid for those who do (approximately 120,000 AMD/month).

Navasard papik’s eyes sparkle when he recalls memories experienced over his lifetime. His journey was full of failures and success. Life was quite generous towards him, as he had a father who, even though was an illiterate refugee from Western Armenia, strongly valued the power of education and sacrificed everything for his son’s future. Thanks to him, Navasard papik went to university and then devoted 30 years of his life to being a teacher of Armenian language and literature. His voice is full of compassion and love while talking about his family: three sisters and four brothers who have passed away, his grandson whom he has not seen for almost two years. No, Navasard papik does not blame anyone.

Besides the old age homes, the ministry provides two other types of services as well, including home care services and senior citizens clubs. “If a person has a house, it seems more reasonable and liberal to continue living in their house and receive the needed services at home,” noted Gevorgyan. The problem with home care services, she explained, is that because of scarcity of financial resources, the number of visits is a maximum of three times per week, which as the practice has shown is not enough.

“The new government’s policy is targeted towards the deinstitutionalization and transformation of old age homes into community-based service providing centers, with better conditions and high quality services,” she explains. The third type of service, senior citizen clubs, which according to Gevorgyan is the most preferable among the three, is meant for people who are physically able to leave the house, receive the needed services in the club, and return home in the evenings.

Seventy-one-year-old Navasard papik says that he voluntarily came to the old age home, because of the complicated relationship with his wife. While realistic, he’s also optimistic and works to avoid disappointment and appreciate whatever he has. He was hesitant to state that the old age home provides ideal living conditions, but even the dull colors of the wallpaper and 42,000 drams pension are enough for him. Despite all the difficulties, Navasard papik feels blessed to have a roommate like Petros, feels proud that he has educated generations, and feels fortunate to be surrounded by caring nurses.

When being admitted to an old age home, the first requirement is the consent of the senior citizen; it should be on voluntary basis only and the person has to apply to local social support center. According to the law on social assistance, people eligible for the services at a home are those who are 65 and above as well as people with disabilities, who are 18 and above. Gevorgyan clarified that it is the responsibility of the local social worker to evaluate the needs of the applicant, including their socio-psychological conditions as well as the health status in accordance with the already set needs assessment methodology.

There are some conditions that do not comply for general day care centers, such as infectious or sexually transmitted diseases, mental disabilities, or tuberculosis. “The social worker plays a key role in the procedure and is tasked to explain and clarify all the available options which would allow a senior citizen to make an informed decision,” Gevorgyan explains. “And if the person complies with all the requirements, the ministry assigns an old age home, based on availability.

Gevorgyan says that the entire procedure, if there are no complications, takes a maximum of three days, mainly because there are no waiting lists for the general type of old age homes. The situation, however, is different for special homes where the procedure might take up to several years because of the scarcity of available places and large number of applicants.

Seniors in Armenia end up in old age homes for a variety of reasons, according to Gevorgyan. They include the need for housing, strained family relations and most commonly, dire socioeconomic conditions.

Meanwhile, Petros papik is impatiently waiting for his turn to talk about his journey. He proudly remembers Oshakan, the village where he was born. “Mesrop Mashtots, who created the Armenian alphabet was also born there. It was thanks to him that our nation has preserved its national spirit and identity,” he says. Petros papik worked as an ambulance driver for almost 20 years, the most memorable and adventurous years of his life.

Speaking about the challenges, Gevorgyan says that for public old age homes, the most urgent problem is related to the poor conditions. “All the buildings are old and over time conditions have become horrible and renovation would require significant resources, which is not included in the allocated budget,” she says. The overall budget is 2.5 billion AMD ($5.1 million), which is primarily spent on medicine, food, clothing, and hygiene products. The cost per person in a general old age home is 90,000 AMD/month ($187 US), while for special centers it is 150,000 AMD/month ($311).

The second critical problem is related to rooms, which are intended for large numbers of residents and have been constructed without considering the need for personal space. The third pressing issue is limited staffing One nurse provides care for 30-40 elders, for those who are bedridden the ratio is 1:10, which is a large number for the amount of work that a nurse is required to do. In Norway, the ratio is two caregivers for each senior, in Russia the ratio is 1:5, in France 1:2. Of course, all of these contribute to the poor quality of the services provided.

Suddenly, Petros papik picks up his family album and starts carefully wiping it with a cloth. For a few seconds, he is standing still, tears running from his eyes. As he opens the cover, the scent of lavender floats through the small room. The old sepia photos take him back to his wedding day. He is wearing a tailored suit and looks stunning with his wife, Arusyak. Petros papik considers himself very fortunate because he spent 47 years with the love of his life. The fact that they had no children was never a reason for misunderstanding. Petros papik’s love has not faded. The wall beside his bed is covered with photos of Arusyak, and a bouquet of artificial flowers is always in front of them. He feels her presence day and night.

Even though Petros papik has lost a sister, four brothers, and his lovely car Zaporozhets, he has not lost his hope for the future. He still believes in the Armenian youth, he believes that decades later, when he will not be alive, Armenians spread all over the world will finally return to their homeland.

About 60 percent of those living in old age homes have children, and the majority of children (about 60 percent again) are male. The number of visits are significantly small, on average 10 percent of seniors are visited regularly by a relative. Navasard papik and Petros papik consider themselves lucky to know each other. They are thankful to God that their destinies collided in that small room. They are thankful to the senior’s facility that gave them a home and hope. Do they feel happy? Sometimes, but not always. No one would really know because no one has ever visited them.

wow i cant believe nobody visits Bedros & Navasard papik or only 10% seniors living in old age homes receive visitors. thats a big shame!