When eating out, you impatiently wait for your order to arrive, secretly hoping yours is going to be the best dish at the table.

A white sauce that I assumed had some fruit in it was gently blanketing finely chopped pieces of freshly boiled carrots, beets and some cabbage. This is what I was served, however, it was not the dish I was waiting for. As it turned, out the organizers of the event I was participating in had messed up my order, and this meant they planned to serve me vegetarian dishes for a week.

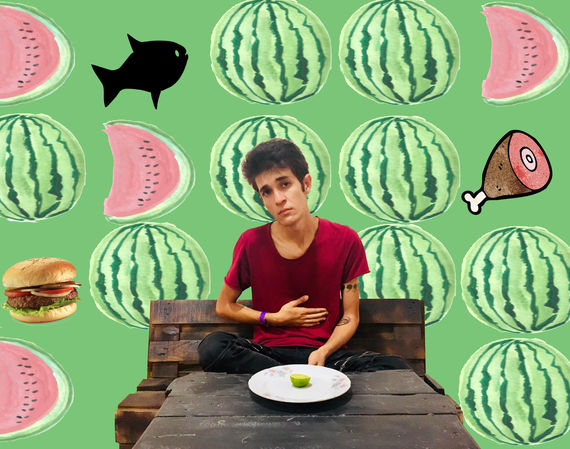

I’m a meat eater, so are my friends and their friends. Eating a lot of meat is also a “side effect” of the Armenian national cuisine. Meat is the pride of the table and an inseparable part of Armenian traditional dishes. I’ve never found vegetarian dishes particularly enticing but that day I did not return the order. I decided to try it, and what’s more, I took it as a challenge to become a vegetarian for a week, . It was complicated, it was interesting.

More and more people are giving up animal based diets in the world. The number of vegetarians and vegans is growing in Armenia as well. The question is to what extent are these “non traditional diets” compatible with social settings in Armenia and local culinary recipes?

“They ask me, you don’t eat meat at all? Not even chicken? Not even boiled chicken breast?”

Mariam Babayan.

Mariam has not eaten meat in two years. “I love being in the kitchen, I love cooking,” says Mariam. “There was a time when I was good friends with meat. But then one day I witnessed a lamb being slaughtered.”

The scene would not leave Mariam alone for a long time, the only thing to do was to give up meat. “My conscious is clear this way. Now I don’t like meat at all. I make harisa without meat, I also make vegetarian dolma.”

Of course it is not easy to give up meat in a society where most restaurants and cafes don’t take vegetarians and more so vegans into consideration. Not to mention family gatherings where the main dish is khorovadz – grilled meat garnished with onions and pepper.

“When I tell people I don’t eat cooked food, they ask me if I eat my meat raw as well.”

Lilit Hovhanesyan

Not everyone who is a vegetarian has decided to save the animals. Lilit Hovhanesyan changed her diet for health reasons. “I used to say that there are too many human problems to be solved before we can get to the animals,” says Lilit. But that changed one day.

There was an online article about eating raw titled Сыроедение from the Russian, (Сырое – raw and едение – eating) but Lilit misread, thought it was about eating cheese (Сыр – cheese is very similar to Сырое – raw) and clicked on it to learn more about eating cheese. “It was the first time I was hearing about it,” says Liilt. “I wanted to understand if eating raw food is safe, if it is filling and what would be the purpose of it.” And since the vegan raw food movement was about health, longevity and beauty, Lilit took an interest and decided to study it further.

The idea behind the vegan raw food movement is that people were initially vegans and ate everything raw. This seemed natural to Lilit and at one point during her quest to find out more, she passed the point of no return.

Lilit now has her own blog where she posts health food recipes for vegans, gives lifestyle advice and of course, talks about her own experience of raw eating. “I started the blog in January but I began to update it more regularly when I realized that people are looking for such information. The responses were quite encouraging, it motivated me and I in turn motivated others,” Lilit remembers.

The first month was about giving up meat, then dairy and then eventually it came down to simply washing the produce and eating because the raw eating movement does not assume anything else. Lilit believes cooked food is simply a repository of poisonous material that accumulates in the organism over time. To cleanse means to get rid of the accumulated harmful material, explains Lilit.

“I simply understood that I have not been honest with myself, or that I no longer agree with the decisions I’ve made in the past.”

Izabella Khanzratyan

The rabbit that unexpectedly appeared at Izabella’s house three years ago was the reason she decided to reevaluate her love for animals: “It made me wonder about why people necessarily need to eat meat, to what extent is meat indispensable?”

One morning Izabella opened her eyes and decided to close the chapter in her life where she used to eat meat. “There was a lot of prior study and literature at the base of my decision,” says Izabella, “I understood that I no longer agree with the choices I had made before.”

When her friends found out that she had made a complete transition to vegetarianism, they split into two camps – those who did not think it was a big deal and those who went on a rant of sarcastic remarks about a person who used to have an appetite for meat and then went vegetarian.

This bothered Izabella. Society rarely gives people a chance to change but she believed a person can not always march in place, do the same thing over and over again; people need to be moving forward and develop. Izabella decided to surround herself with people who know how to respect her decisions, just like she respects theirs.

People think that being a vegetarian comes with restrictions, deficiencies. That is nonsense says Izabella: “In 2016, when I was climbing Mount Kazbek with the Armland group, the guide was extra attentive towards me throughout the climb. He was constantly reminding me to eat meat or a piece of basturma if I start to feel faint. I categorically ignored his suggestions because I was sure that my health would more than allow me to conquer the peak. I still remember the scene that opened up from that peak with the greatest pleasure.”

“I believe the situation has improved over the last several years. Before, it was complicated and very unpleasant. They would tease you, the service would get worse and you only had 0.1 percent of the menu to choose from.”

Narek Buniatyan

Narek Buniatyan has been a vegetarian from the day he was born. “I don’t know if it is a coincidence or luck but I was born to vegetarians. And when you are born in a family that does not eat meat, becoming a vegetarian yourself is predictable, logical and natural,” he says.

Narek says his parents never insisted that he give up meat, they never had a serious conversation about it either, at least not when he has a child. Discussions began after Narek came of age. “They would show me material about how meat is processed, what dangers it contains but it was not only a one sided approach, they also mentioned the benefits of eating meat,” he recalls.

The rest was a matter of choice, one that Narek made pretty early on. In his twenties now, Narek has never tasted meat. “I tried soya meat once and spit it out, the taste was very unpleasant,” he says. “I never feel like I’m missing out on anything or that there is something out there that I want to try.”

Even though it is easier now for a vegetarian to eat out, there is still room for improvement. “I believe the situation has changed over the years. Before, it was complicated and very unpleasant. They would tease you, the service would get worse and you only had 0.1 percent of the menu to choose from,” remembers Narek.

Still, quite recently, Narek had gone to a restaurant in Gyumri and inquired if they had anything without meat: “By some curious logic, I was told that they had ham and cheese, hot dogs and barbecued fish.”

***

Dietary social norms, customs and traditions involving food are associated with family, friends and social bonding, especially in many Armenian households. Sharing food is indeed a social ritual and those who have decided for a variety of reasons to be vegetarians or vegans can sometimes come face to face with social isolation.

Luckily, however, this is slowly beginning to change. And today, there is less and less need to excavate menus to to find something to order and the good old reduction technique of asking for a Caesar salad without chicken or pizza without ham will hopefully be a thing of the past.