This paper is the result of a conversation between three women on the role of writing in forming communities that open up spaces (“rooms”) for female expression. It is part of a larger conversation on women writing that I started three years ago to find the answer to questions such as:

What circumstances make women writing/literature possible?

What do women own in their writing?

What is the meaning of this ownership?

To answer these questions, we looked at Virginia Woolf’s A Room of Her Own (1929), Helene Cixous’s The Laugh of Medusa (1975), and Luce Irigaray’s Speculum of the Other Woman (1985).

“ Illiteracy and literary obscurity prevented women from shaping the history of their own writing. ”

The Room and the Circumstances of Writing

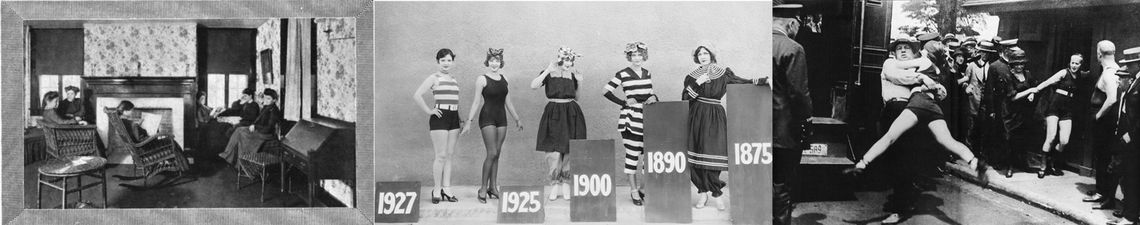

In A Room of Her Own, Virginia Woolf writes, “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” The room is the symbol of financial security, time and individual freedom. Before the 20th century, the majority of women, even in industrial nations, were deprived of basic requirements that enabled them to write. Writing was considered an extravagant activity that belonged mainly to those aristocrat women with strong social connections who could get their works published.

Today, the rate of female literacy in the world is still eight percent lower than the rate of male literacy (The World Bank); poverty and hunger are more common among women. As a result, writing remains a luxury for women. This situation leads the majority of women in the world to believe that they cannot write. They think they do not have the talent, or writing is not for them.

What is writing after all? Isn’t it a personal language? The same language in which we think and feel? In most countries, writing is not a requirement for learning, but a subject like mathematics or physics. Learning is supposed to happen through memorization rather than through critical thinking and writing and analysis and group discussion. Students are considered as bearers of knowledge, not knowledge producers. To prevent citizens of their countries from personal expression, totalitarian regimes promote this simple equation of memorization and learning through public education. In schools, students learn to memorize and repeat the thoughts of certain intellectuals who are mainly male.

A person who cannot think independently is often incapable of writing, too. Writing is a valuable individual experience. When thoughts do not get a chance to be expressed, they are often forgotten or suppressed. Perhaps, to avoid the recurrence of such tragedy, Helen Cixous asks women to write with the white ink of their milk (The Laugh of the Medusa). This is the ink which can overwrite historical accounts of male hegemony that have silenced many throughout history. These overwritten accounts as women testimonies do not follow male-dominated rules of writing and aesthetics. Every time a person thinks that s/he cannot write, we should ask if s/he has tried to write with this white ink which is not exclusive to women. Has this person censored his or her thoughts to conform to established rules of writing and patriarchal structures of language? If women, as Woolf suggests, do not strive to mirror back “the figure of man,” will they still find themselves incapable of writing? Have the women who believe they cannot write ever tried to write in their own language?

Since intellectuals and writers are among shapers of history, women’s contribution in forming social and cultural structures and laws has so far been very low. To empower ourselves, we need to realize that we can write. Thinking and writing are not talets exclusive to a few. Women’s inability to write is an illusion that brings about the loss of our voices. One without a voice cannot converse with others. To struggle against this loss and against further elimination of women from fashioning history, we would need to see that we are able to think and write.

The Room and the History of Women’s Writing

The second meaning of the room is the writing legacy that women lack. The literary canon – the authors whose books are named as the most important and influential literary creations are mainly male. Some examples of the Western literary canon are Homer, Aeschylus, Euripides, Virgil, Horace, Geoffrey Chaucer, Dante, Shakespeare, Rabelais, Molière, Cervantes, Milton, and Goethe. According to Woolf, male writers see themselves as a “natural” continuation of this lineage, while the women writers see themselves detached from it. Illiteracy and literary obscurity prevented women from shaping the history of their own writing. Many women writers such as Emily Dickinson were not recognized during their lifetime and were often turned down by the editors of literary magazines and publishers. In other words, the feminine world has been often empty of the historical legacies that the masculine room possessed. Women were historically cut off (removed) from the writing tradition.

The historical absence of early women writers whose works could create a legacy for the ones who came after them in later centuries led the newcomers to doubt their writing ability and contributed in women’s further absence from the literary canon. If, like Heidegger, we take language to be “the house of the truth of Being” (Letter to Humanism), given the underrepresentation of the women’s literary voice, we can infer that women had only a limited space–perhaps a space much smaller than a cage–in the house of Being. Another way to use Heidegger’s ontological metaphor to illustrate the status of women’s absence or underrepresentation from literary and philosophical conversations is to say that women occupied “a room of silence” in the house of Being.

The problem of absence of women’s literary tradition is also partly due to the historical disconnection between individual women writers. While men writers created legacies through which they felt links among themselves and their writings, women writers stand like isolated islands separated from one another. A contemporary example is the Iranian writer Simin Daneshvar (1921-2012) who is considered as the founding mother of novel writing in Iran. While a predecessor in her own right, Daneshvar did not create a legacy of female novel writing because the writing arena was occupied by male writers such as her husband Jalal Al Ahmad, and Sadegh Hedayat (who although created fewer works are considered as the backbones of Iranian literature). In Armenian literature, women have been portrayed as the vessel through which traditions, memory and language are sustained. The voices of women writers, few as they have been and are, continue to be absent from the collective consciousness of the Armenian nation. Few names can be recalled – Srpouhi Dussap, the founding mother of novel writing (1840-1901), Zabel Yessayan, Sibil (Zabel Asadour) – yet even these women are not given the attention they rightly deserve in the Armenian literary canon.

This lack of history and memory threatens women writing. The lack of a feminine legacy, unlike the male legacy, was not built based on the average and below average pieces created by women. This loss has created a feeling of inferiority and perfectionism in women as they often think that their writing is less valuable or less professional, thus less worthy of presentation. Women writing was often measured with the same aesthetic standards, which the male written legacy generated, and because of which, was always considered inferior and less refined. An example is the male writers who avoid addressing their female critics.

The publishing industry run by male editors has been influential in defining the canonic texts. Woolf discusses this issue while being aware that her husband’s editorial career is the main cause of the publication of her works. Every society needs women publishers whose standards do not follow the standard male canons. Unfortunately, as soon as women get involved in the industry, many of them accept the existing standards and follow them. Lacking a history of their own, women have been acting as the “mirrors,” the revivers of male standards, diplomacy, values, writing, morality, thoughts, and emotions. Woolf writes, “Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size. Without that power probably the earth would still be swamp and jungle. The glories of all our wars would be unknown.”

The Room as the Genre of Writing

Unlike poetry and drama, which were originally created by male writers, the novel could be considered a female genre. Daniel Defeo’s contemporary writer, Aphra Behn is equally considered the founding mother of the novel. Throughout the eighteenth century, educated gentlemen were keen to be seen reading or speaking about poetry and classical drama, but the novel, in prose, represented the stories of ordinary human beings and their daily concerns. According to Woolf, it was easier for women to write fiction because they were accustomed to it through storytelling for children, and writing memoirs and journals. Domestic life, according to Woolf, empowered women to write longer pieces that male writers due to their social busyness could not generate. The novel has become the genre where men didn’t have a prolonged history and where the first female discussions (in the works of Mary Shelley, George Eliot, Jane Austen and the Brontës) started. The fact that no perfect form existed in novel writing, and that women were free to create their own structure gave them enough room for thinking and creation. While societies have regularly created standards of female morality and sexuality, fiction writing has become a media for expression of their marginalized existence. The novel, as a genre that didn’t have a history, set the first women writers free. Today genres such as philosophy, screenplays, and history are still considered male dominated.