From emerging Armenian artists across the globe to Armenian-American talent in the United States, [Art Speak] will spotlight the dynamic and diverse Armenian art world and more.

Listen to the article.

Like a medieval alchemist, artist Eozen Agopian transforms objects elementally. She threads many of her canvases with intricate needlework and weaving, incorporating found fabric to create richly textured pieces that challenge notions of space and time. She also creates fantastical three-dimensional patchworks that hang from rods and form sculptural pieces that verge on installation art. When she is “merely” painting, Agopian’s delicate hues and use of light echo the work of another Armenian artist, Abstract Expressionist Arshile Gorky.

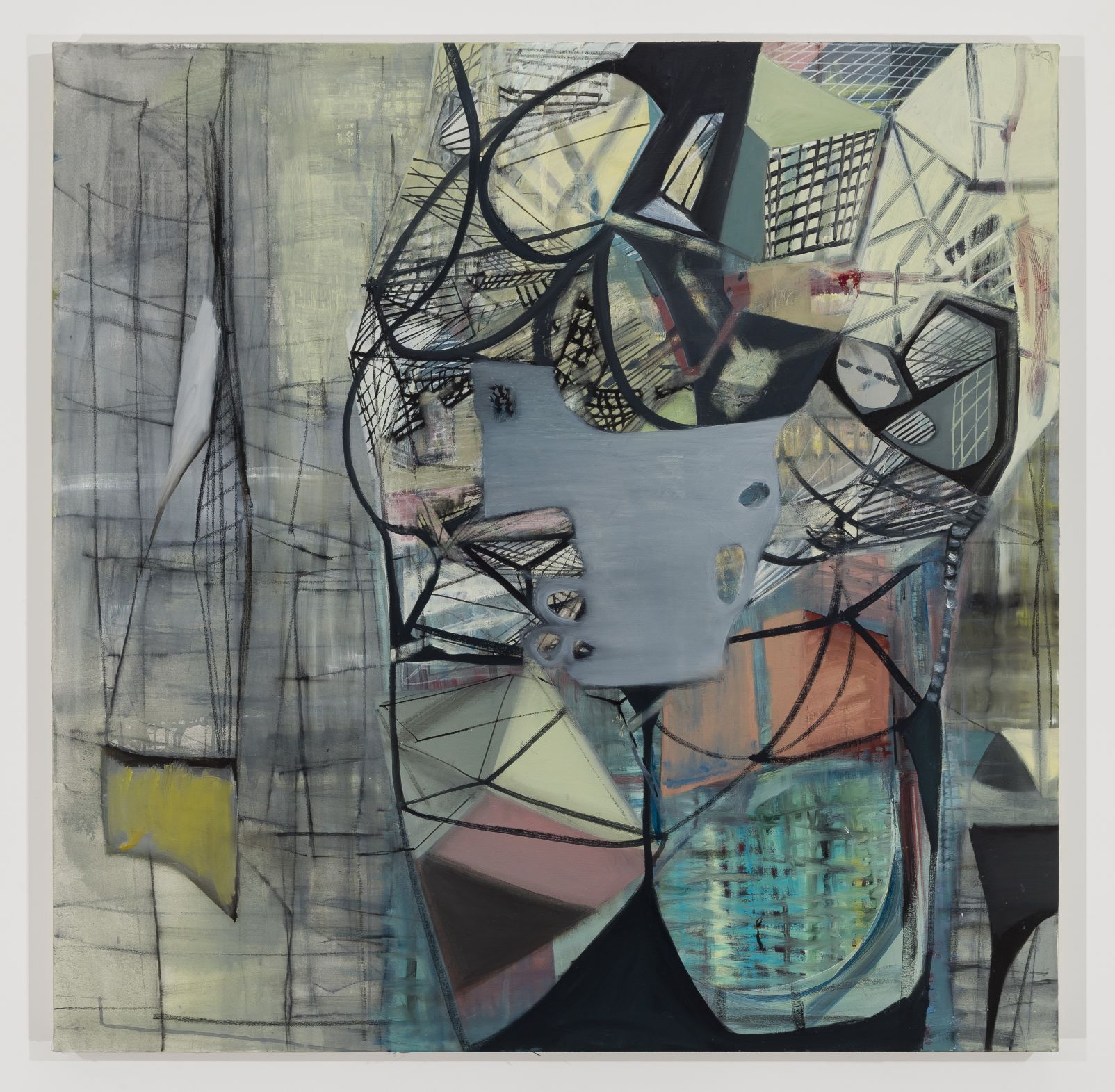

Afterstorm, 48×48 inches, acrylic and oil on canvas, 2014.

Her large, four-foot-square Afterstorm, painted with acrylic and oil on canvas, recalls the color palette of Gorky’s Garden in Sochi, as well as the geometric inventiveness of de Kooning. At once brooding and bracing, it captures the emotions one feels after an actual tempest, or an emotional encounter gone awry. Here the curves and geometric shapes create powerful negative spaces that guide the viewer’s eye across the canvas. Agopian decided to pursue art after reading Kandinsky’s The Spiritual in Art, and a sense of spirituality pervades her work. The connection to the past, the link to women who lived by the needle arts, and the powerful effect that her geometric collages produce on the viewer all contribute to transcendent artifacts. Other influences on Agopian’s work include Rothko and Hans Hofmann for their use of light, as well as Eva Hesse and Louise Nevelson, who also created sculptural cosmologies from found objects.

Agopian grew up in Athens, where she attended French and Armenian schools. Later, she traveled between continents, earning several degrees, including an MFA from the Pratt Institute in 1993. She then patiently built a successful career, exhibiting in leading galleries and museums worldwide, including PS122 Gallery and Lesley Heller Workspace in New York City, AAW Gallery in Beijing, and Freud’s Dream Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia. Her renown is perhaps greatest in her native Greece, where she has exhibited at the State Museum of Contemporary Art and the Museum of Byzantine Culture—both in Thessaloniki—and at the prestigious Hellenic American Union in Athens. In her signature pieces, Agopian carefully threads onto the painted canvas and combines recycled fabric with paint to create unique, almost cubist multimedia assemblages. These works range in size from small, intimate 10 x 8-inch pieces to large, dramatic ones measuring up to 3 x 3 feet, which require months of meticulous stitching. “Thread holds a symbolic meaning for me,” Agopian explains. “As a young girl growing up in Greece, needlework kept us busy in the late afternoons. That was my first experience with canvas, and I was fascinated by the cleanness, vibrancy, and variety of the colors of thread.” She describes her dual love for needle and brush as a balance between something precise and almost Zen, and something explosive and emotional.

Crashed, 47.2×43.3 inches, mixed media with acrylic, oil, pastels

and thread on canvas, 2012.

The threading and layering in works such as Safe (acrylic, oil, and thread) and Crashed trap and reflect light through the fluidity of the medium: “I sew different layers of colored yarns to create chromatic filters where shimmering shapes are visible underneath.”

While Agopian does not consider herself a feminist per se, she is in fact honoring the tradition of women who for centuries toiled with their hands both at home and in factories. Difficult, painstaking work, but also meditative in nature: “By merging hundreds of disparate threads from different patches of material—unrelated by texture, origin, or ownership—I associate my work with the intensive labor of the worker in that industry. It’s also a tribute to the first women garment workers who protested working conditions in the needle trade and demanded equal rights with men.” Agopian speaks of the physical toll her work takes on her body, as she pricks her fingers and strains her eyes for countless hours. The meticulous cutting, pasting, and use of found fabric also metaphorically recalls her family’s history as refugees from Smyrna and an artistic tradition that could easily have been lost: “This is my grandmother’s story, really. Her lace was beautifully crafted with a needle using the Nazareth technique—a discipline that requires great patience and concentration.” Agopian insists that the distinction between “art” and “craft” is artificial: “Craftspeople are artists, and artists are craftspeople as well.” Like the boundaries between countries and people that conceptual artist Meri Karapetyan elsewhere deconstructs in her large untitled wire installations, Agopian crosses the boundaries imposed on artistic production by classical art historical discourse. She does so in part because she believes that art must be both accessible and enlightening. Her own finished pieces offer enchanting kaleidoscopes of colors and shapes that seem to speak directly to the viewer.

Between Two Continents, 65×62 inches, mixed media with acrylic,

oil, fabric and thread.

In her larger sculptural works, Agopian uses broad cuts of fabric woven onto the canvas to create three-dimensional multimedia pieces that recall the cubist period of Braque and Picasso. Between Two Continents reflects her experience as a diasporic Armenian who has traveled between America and her native Greece throughout her life. When installed hanging from a bar, it commands the surrounding space with its physicality and vibrant decorative patterns that recall a lush Klimt, or perhaps Joseph’s biblical technicolor raincoat. Another equally powerful work Thin Skin (mixed media with acrylic, oil, fabric, and thread), demonstrates the extent to which a canvas also functions as a skin on different levels. These two pieces also make an indirect comment on the vanity and waste of fast fashion where fabric and even finished clothing are discarded, in a world where many cannot afford to buy these items new.

Agopian’s life seems steeped in ancient culture and art. “I was influenced by my upbringing in Greece, by my Armenian heritage,” she says. “And everywhere I go, art seems to follow.” Her family, for example, includes an uncle who was a master upholsterer in Detroit. Meanwhile, her husband and daughter belong to the famed Tsakirian dynasty of luthiers. For four generations, they have been fashioning classical instruments such as ouds, guitars, and bouzoukis from scratch for renowned musicians such as Udi Hrant and Manolis Chiotis. Upon first viewing Agopian’s threaded canvases in her East Village studio, a stringed instrument came to mind: one wanted to pluck the threads on the canvas and see if music might emerge! In 1997, Agopian visited Armenia, where she experienced an artistic epiphany: “I saw that the colors there were warmer, less blue, than in Greece.” She also recognized herself in the play of light: “The churches really moved me, especially the light pouring through the openings. In the end, my work is about light. I aim to create visual parallels between rational and cosmological worlds through constructing and deconstructing, layering and erasing, scraping and marking, unraveling and reconnecting.” Here, Agopian affirms Freud’s observation that art connects with people at a subconscious level and helps them to overcome the alienation inherent in human existence.

Accordingly, Agopian’s work lends itself to multiple interpretations. In 2022, Atamian Hovsepian Curatorial Practice presented her work in the context of deconstructing time and space through found objects and sense memories. This Chelsea group show, The Future of Things Past, also included Judith Simonian, Linda Ganjian, and Melissa Dadourian. The following year, Agopian held a solo exhibition, Overcrossing, at the High Noon Gallery on New York’s Lower East Side, which emphasized the crossovers in her work from one context, medium, or world to another. And her 2024 show Shreds of Light at Officinenove in Rome displayed older works which contrasted with new pieces produced during a residency there. Agopian is currently preparing for her next solo exhibition, which will take place this coming November 2025 at the prestigious Eleftheria Tseliou Gallery in Athens. There she will present new mixed medium, three-dimensional paintings with thread and fabric. Titled See-thru, it promises to be a revealing experience for all.

Learn more about Eozen Agopian: www.eozen-agopian.com