Visiting one post-Soviet state, you can then recognize it in all others – the similar patterns of urban planning and the identical buildings, structures, roads, pipes, wires, tiles, etc. However, an outsider delving inside under the extreme familiarity of the material environment finds an extreme “strangeness” of social interactions and practices. The “Outside In” series is about emplaced paradoxes and nuances. It spotlights the mundane in Armenia’s peripheral locations, where the seemingly unspectacular encounters with people and things allowing us to capture the unique features of the territory.

Listen to the article.

Outside In

Essay 19

The morning was painfully early, and the weather matched my mood; grey, wet and resolutely unpleasant. Together with my colleagues, we embarked on a work trip to Sisian. I had never properly visited the town before, only passing by on my way to more distant places further south. Running on little sleep and bad coffee, I was already caught in a fog of irritation. Sometimes it is a blessing to be a pessimist: you are either right or pleasantly surprised. Sisian, regrettably, supported the former claim.

In many literary traditions, writers immortalize unremarkable towns as characters of their own, places that exist less through any active will than through a slow, inevitable accumulation of habit. Sisian seems to be this kind of place. It is neither charming enough to be loved nor offensive enough to be despised; it simply exists, occupying a peculiar purgatory of (post)Soviet provincial mediocrity.

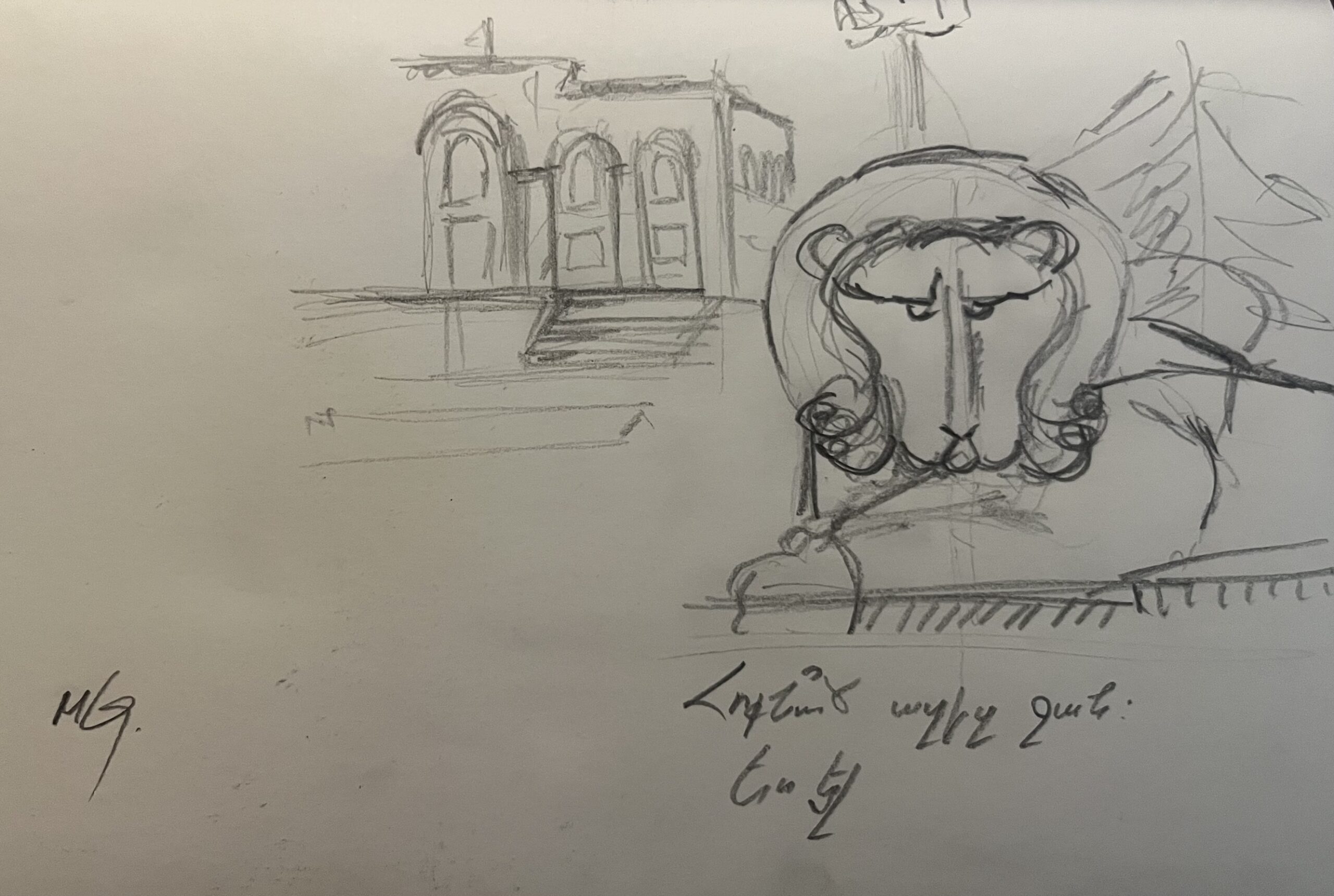

The town center offers exactly what one might expect: a scattering of administrative buildings, designed with the bleak lack of ambition typical of Soviet middle-rank bureaucracy. Just gray buildings that serve a function. The main square, where the towering statue of Lenin once stood pointing firmly toward the “bright future” is now empty. No new monument has dared to replace this space. Two flat-faced lions, carved from stone, sit like exhausted sentinels emotionally defeated by the flow of time. The only color in the architectural ensemble of the square is a bas-relief of the Soviet red flag, reportedly camouflaged into an Armenian tricolor for national holidays. A gesture as symbolic as it is half-hearted.

We walked through the town beneath the persistent drizzle gazing at the tired apartment blocks with peeling paint and laundry lines, small shops and workshops blazed their petty colorful plastic signs. We passed a massive water fountain, a signature piece by Rafael Israelyan, who unfortunately built so many similar fountains across Armenia that their individuality was lost in their repetition. Not far, there was a crumbling local Dashnaktsutyun party office marked by a red flag. Neighboring it was a clothing shop called “Mania,” written in similarly red letters. Of all the local town’s sights, our guide’s stories and earnest commentary, only this image—Dashnaktsutyun Mania—stayed firmly in my mind.

The surrounding landscape aspired for grandeur with its mountains and winding rivers, but failed to impress after one has seen Armenia’s truly spectacular natural wonders elsewhere. Sisian’s few historical sights clung to life through minimal maintenance, just enough to fend off collapse, but not enough to inspire. What further frayed my nerves was the guide’s repeated comparisons to Goris; as if Sisian was a neglected sibling, tragically overlooked because of lack of tourism investment. I understand the instinct to defend one’s hometown; every cook praises their own broth. But frankly, in my not-so-humble opinion, Sisian cannot hope to match Goris with its haunting cave dwellings, authentic architecture, fragrant rose bushes and golden autumn alleys. The harsh truth is that not every place is meant to be a tourist destination, no matter how appealing the idea of tourism as an economic panacea might be.

As the day wore on, my irritation thickened into something almost theatrical, until we finally settled into the warm, quiet restaurant of our hotel. Waiting for dinner, I glanced around, and my eyes fell upon a painting hanging on the far wall. At first, it appeared to be just another mountain landscape, a safe decorative choice for a small-town hotel. But then something about it, the way the paint seemed to shimmer, the way the mountains hovered between solidity and vapor, drew me in. The forms were monumental, mythic, yet the texture of the brushwork suggested transience, as if the mountains themselves might dissolve at any moment. The signature read “Armen Hakobjanyan.” A quick search revealed he was a contemporary artist of about my age born right here in Sisian.

Around the room, I noticed more of Hakobjanyan’s paintings: minimalist landscapes reduced almost to abstraction, rendered in the severe cold palette of Syunik’s earth and sky. They were not depictions of real places, but emotional distillations, imaginary landscapes that spoke more about essence than detail. His art seemed to whisper something that the actual town of Sisian could not: a profound, haunting sense of timelessness.

Hakobjanyan’s work immediately reminded me of Hakob Hakobyan, another master who captured the soul of the Armenian landscape. Hakobyan’s “quiet” surrealist paintings often portrayed the worn textures of provincial life with peeling doors and desolate courtyards. A meticulously painted deep melancholy. His monochrome palette and detailed static graphic hinted to undercurrents existing within the seemingly ordinary scenes. Hakobjanyan, however, takes a different approach. He skips detail and plunges straight into the realm of pure emotion. His mountains are not actual mountains but symbols: enduring, indifferent, vast. They are far beyond human ambition or despair.

There is a profound connection between the evolution of abstraction and the environment that birthed it. When reality itself becomes deadened, the only meaningful artistic response is to transcend it. Artists like Hakop Hakobyan do this by excavating beauty from ordinary details. Armen Hakobjanyan pushes even further, seemingly abstracting not the surfaces but the very affects of existence. Sisian’s battered cityscape, its architectural conventionality, and its traits of abandonment, all of this becomes strangely legible when looking at Hakobjanyan’s art. It is not the material failures of the town that matter, but the silent, eternal elements that endure beneath the passing absurdities of history: stone, mist, light, shadow. In this reading, Sisian is a raw, unfiltered fragment of the sublime, a reminder of human smallness against the vast, indifferent nature.

Sitting there, warmed by the restaurant’s dim lights and the persistent resonance of Hakobjanyan’s art, I realized that perhaps Sisian’s true poetry is embedded not in its streets or squares, but in the invisible dialogue between land and sky, between crumbling stone and drizzle. It is a place of brutal honesty that refuses to pretend, and instead, invites those who are patient enough to look past the surface into something more enduring, more elemental, and, paradoxically beautiful in its mediocrity.

Drawing by Maria Gunko.

See all [Outside In] articles here

Maria Gunko is a DPhil Candidate in Migration Studies, Hill Foundation Scholar at the School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography University of Oxford. Since 2023, she has joined Yerevan State University as a Visiting Professor. Maria holds an MSc and Kandidat Nauk (Russian post-graduate degree) in Human Geography.

Maria’s research interests lie in the intersection of urban studies and social anthropology, including ethnography of the state, infrastructures, and urban decay with a geographical focus on Eastern Europe and the Southern Caucasus. She is the co-editor of one monograph, author of over thirty scientific articles and op-eds.