Visiting one post-Soviet state, you can then recognize it in all others – the similar patterns of urban planning and the identical buildings, structures, roads, pipes, wires, tiles, etc. However, an outsider delving inside under the extreme familiarity of the material environment finds an extreme “strangeness” of social interactions and practices. The “Outside In” series is about emplaced paradoxes and nuances. It spotlights the mundane in Armenia’s peripheral locations, where the seemingly unspectacular encounters with people and things allowing us to capture the unique features of the territory.

Listen to the article.

Outside In

Essay 12

Contemporary science is built up by a negligible number of immutable laws, the rest are abundant theories waiting to be (dis)proven. Some of them will most probably forever retain their ambiguity, such as the origins of time and space. There is much that we still do not understand about the surrounding world, starting from the very basics. Does this world even exist? Or, as solipsism has it, is the existence of anything outside our mind debatable?

Life is a subjective experience of an individual human resulting from their consciousness and, I would add here, their physical abilities. The visually impaired do not have the physical ability to process visual data, just as the deaf cannot process sound. For them visual images and sounds respectively do not exist. However, this does not mean that they do not exist as a subjective experience. The same holds true for the supernatural world—it exists, despite the fact that (the majority of) humans lack the sensory apparatus to perceive it. This reflects my onto-epistemological stance, which draws on the core principle of jurisprudence: innocent until proven guilty, or in this case, existent until proven otherwise. Having said that, I assume that the so-called “sixth sense” might be the means through which humans access and experience the supernatural.

In popular culture and spiritual beliefs, the “sixth sense” is frequently linked to psychic abilities such as telepathy, clairvoyance, and precognition that lie beyond the traditional five senses of sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch. These abilities suggest that some people may have the power to perceive future events, communicate with spirits, or receive knowledge from sources not accessible through the usual sensory channels. Though widely debated and considered pseudoscience by many, these experiences have been reported throughout history and across cultures.

Science has no concrete explanation, tending to interpret these phenomena as the result of complex cognitive processes rather than evidence of a paranormality. Scholars argue that humans are highly capable of processing information through pattern recognition, memory, and unconscious signals, which can sometimes feel like a “sixth sense.” From a psychological perspective, the “sixth sense” can also refer to so-called “gut feelings” or instincts. This form of intuition is believed to come from the brain’s ability to process subtle cues from the environment, often subconsciously, and to make quick judgments. Irrespective of the explanation, some people do sense things before they come. The focus of this essay is the anticipation of danger in the absence of an obvious threat.

Outliving Stalin’s Purges

When I was little, my grandmother told me the story of Nikolay, a distant relative who outlived Stalin’s purges by disappearing. One day, in 1932, he did not come home to his family, “gone without any trace,” as my grandmother put it. In 1936, officials from the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs [Russian: NKVD] in their traditional black Gaz М-1, referred to as the black Delichon urbica, came looking for Nikolay in the dead of night. To no success. For a long time, Nikolay’s family and friends believed he was dead. Until he suddenly reappeared in May 1956, three years after the death of Stalin and several months after the XX Congress of the Communist Party of USSR that condemned the cult of personality and, indirectly, Stalin’s ideological legacy. Nikolay never revealed where he was or what he did between 1932-1956. The family legend holds that he was sheep herding in Central Asia, poetic but fictional. The only thing that Nikolay ever disclosed was his motive: “I felt the danger in the air. I felt darkness thickening around me. I felt threat’s materially on my fingertips. I know, I know this sounds silly, but… but disappearing for a while would not hurt, I thought to myself. And I was right.” Needless to say, the story left a profound impression on me. I was surprised to hear a very similar story in Ajidzor* from one of my interlocutors.

Escaping Genocide

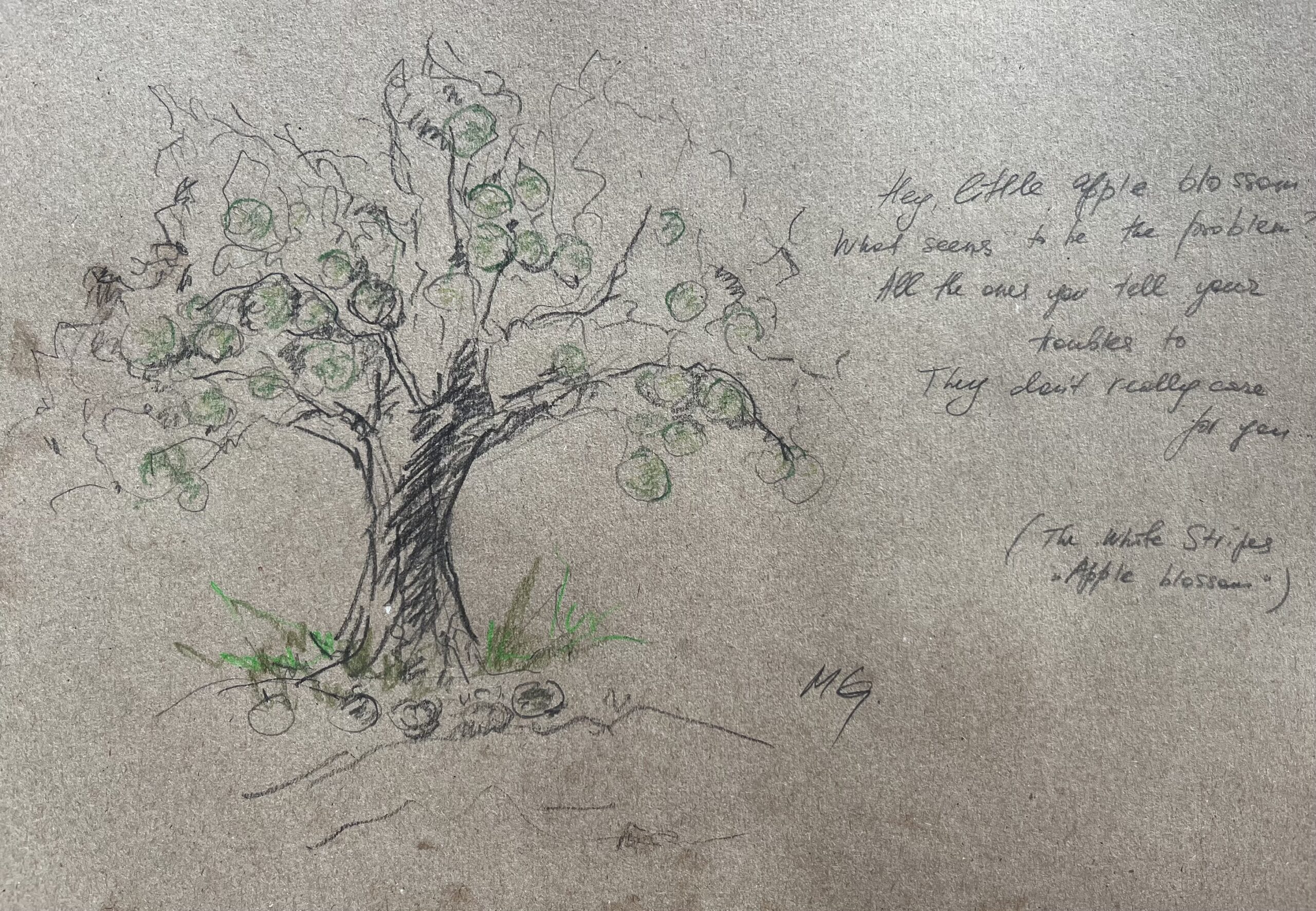

“In my great-grandfather’s garden in Kars was an apple tree,” started Asha, an agile and perky retired engineer, who has become one of my closest interlocutors while doing ethnographic fieldwork. Spending time with Asha and his wife Alla, listening to his endless anecdotal stories was always the highlight of my day. Though I could never tell whether the stories were actually true or (slightly?) embellished, I meticulously took note of them as important artifacts of daily life.

Now, back to the apple tree. It was planted in the garden long before Asha’s great-grandfather, Harut, and stood as a testament to the family’s endurance, deeply rooted in the soil of Kars [present-day Turkey]. Through the passing of generations, it was lovingly cherished, its presence woven into the story of their lineage. In the spring, the tree bloomed, draped in white and pink petals, filling the air with a sweetness so pure, it left visitors dizzy with delight. Asha swore its green apples tasted like honey touched by the divine. The tree, in all its quiet grandeur, was a symbol of the family’s pride and the admiration of all who beheld it.

However, in the spring of 1905, Harut noticed something strange about the apple tree. It looked healthy, but did not show any evidence of blooming. Harut was desperate, trying to understand the issue. He consulted books and experts, and attempted to change routines of care. Nothing helped. The apple tree stubbornly remained flowerless. As days went by, Harut grew more and more concerned. Finally, he voiced his concern to the family: “We should leave this place. I feel the apple tree of my ancestors is not welcome here anymore.” The family dismissed his words as a foolish notion, clinging to the land they had always known. But Harut was resolute and when the time came to leave Kars, he made sure to carry with him the most precious of belongings—the seedlings of the silent apple tree. After days of journey, they settled in a village over the terrain that would in several decades become Ajidzor. Among the first things Harut did along with building a house was planting the apple tree seedling. Time passed, the house became a home, strange became familiar and in the spring the new apple tree burst into magnificent bloom.

When Turkey reclaimed Kars, the Armenians were met with darkness—persecution, bloodshed, and the wrenching loss of homes. Lives were stolen, their paths uprooted by violence. Yet Harut’s family had already fled long before. They credited their escape to Harut’s peculiar gift, his sudden “sixth sense,” ignited by a strange omen from the apple tree.

“Come,” Asha said, as the story came to an end, “I will show you the tree that saved my family.” We walked through the garden, where the tree stood in quiet reverence, its branches heavy with green apples, bending low as if bowing to fate. Asha plucked one, rubbed it clean on his shirt, and handed it to me. It was just an apple, ordinary in every way, except for the story that clung to it.

Two men brought up in dissimilar cultures, separated by space and time, yet sharing a miraculous sense of survival. Did Nikolay and Harut really tap into the supernatural? Was their “sixth sense” prompted by the outwardly? We will never know. Details of their journey will inevitably fade, becoming nothing but dust in the wind. The moral here, however, is that the “sixth sense” is a powerful survival mechanism. Even if we do not understand its workings, we should not dismiss it lightly.

*Author’s note: The town’s name is a pseudonym used for data protection reasons. The text is written partially drawing on data collected with financial support from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 865976).

Drawing by Maria Gunko.

See all [Outside In] articles here