Visiting one post-Soviet state, you can then recognize it in all others – the similar patterns of urban planning and the identical buildings, structures, roads, pipes, wires, tiles, etc. However, an outsider delving inside under the extreme familiarity of the material environment finds an extreme “strangeness” of social interactions and practices. The “Outside In” series is about emplaced paradoxes and nuances. It spotlights the mundane in Armenia’s peripheral locations, where the seemingly unspectacular encounters with people and things allowing us to capture the unique features of the territory.

Listen to the article.

Outside In

Essay 7

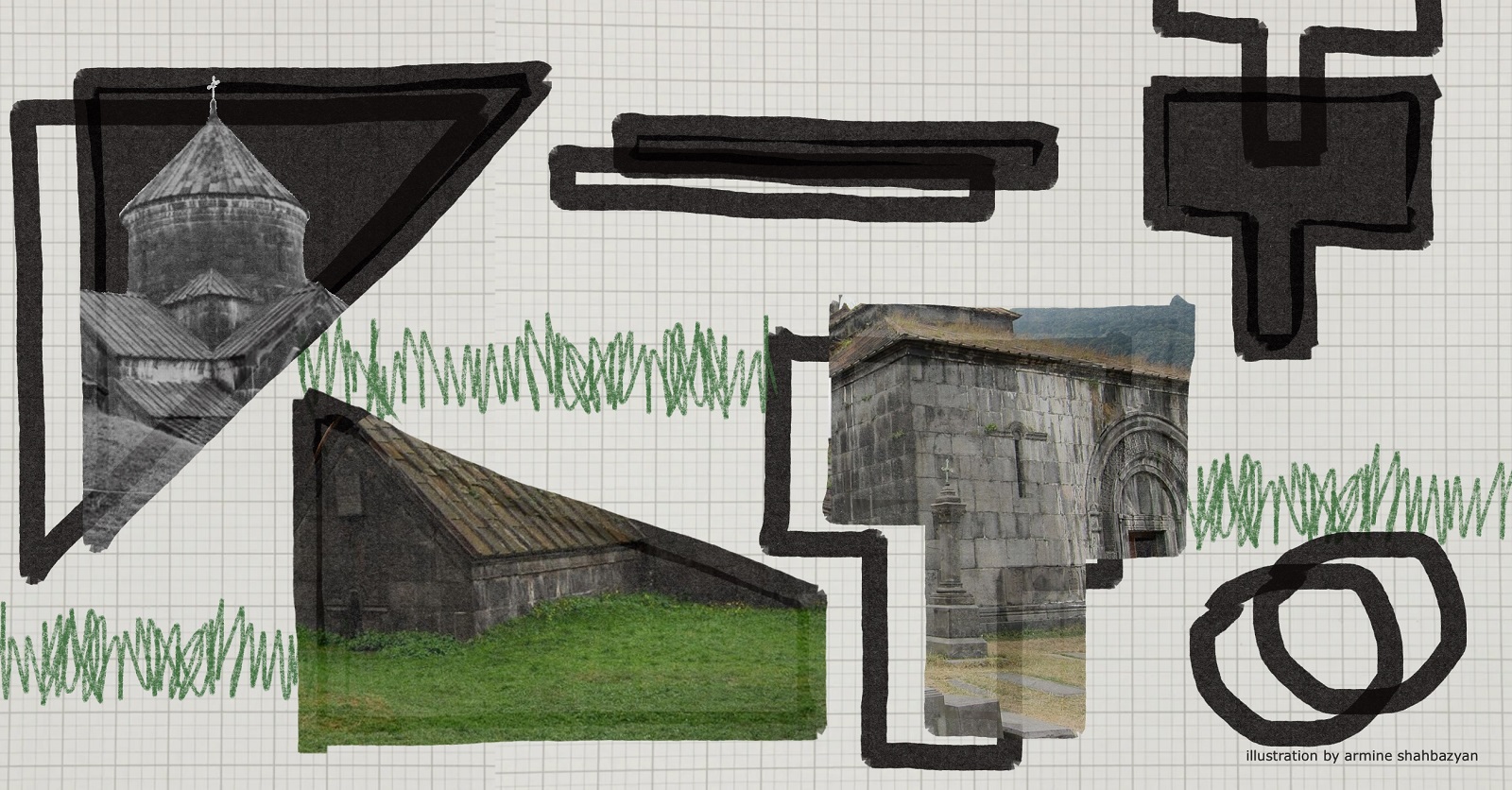

Among the renowned succession of Lori region’s medieval monasteries — Sanahin, Haghpat, Akhtala, and Odzun — Kobayr is somewhat of a hidden treasure. Constructed from grayish local stone, it is hard to spot at the first glance. Nestled organically against the sheer rock of flat mountains, Kobayr stands on the edge of the Debed River’s deep gorge, blending with the natural environment like a chameleon.

Walking to Kobayr was one of my favorite routines while living in Lori region. Two routes lead to the monastery complex. I usually ascended a smooth path through mulberry trees and blackberry bushes, then descended using a snaky path through the village. Beyond the main church, with a desolate altar and broken dome, I ventured into the richly decorated arch and walked over the century old khachkars that pave the surface up to the hilltop chapel. The restoration workers hastily assemble a small table and a bench of rough wooden planks here to chat and drink oriental coffee from small, colorful cups. Over the weekend when work stops, these cups would be gathered tidily in the middle of the table, a reminder of the workers’ presence.

After a moment or two catching my breath while overlooking the town of Tumanyan that lies below, I followed an overgrown path to another chapel secluded in the woods. I spent countless hours there in the cool chambers, reading books, writing notes, or simply daydreaming in solitude. Filled with gusts of wind and birds’ songs, this was my longstanding hideaway, a sanctuary holding intimate secrets.

This place is where I most felt the contrast between the eternal and the fleeting, the essence and the image, and the salutary serenity of the monastery versus the mundane chaos of the settlements below. Against this background, this story is a patchwork of two places and one character who seemingly dwells between them, making a life from what’s available.

The Monastery

The history of Kobayr reflects the intertwined relations of the peoples inhabiting the Caucasus region. Established in the 12th century by the Kiurikian dynasty, a junior branch of the Bagratuni royal house, Kobayr began as a monastery of the Armenian Apostolic Church. It later passed into the hands of the Zakarians, an Armenian dynasty serving Georgian royalty, aligning Kobayr for a while with the Georgian Orthodox Church. Its stone walls are a testimony to those events, where Georgian inscriptions are interwoven with Armenian script. The main church, dedicated to St. John the Baptist, is adorned with frescoes that once burst with celestial blues and earthy reds. Typical for Eastern Orthodoxy, these frescoes, now faded and peeled, stand in contrast to the stern and bare stone interiors found in most Armenian temples.

Kobayr attracts those who seek solace in its solitude, scholars who wish to decode its stories, and travelers enchanted by its serene decay. Names etched into the walls in various languages bear the “footprints” of those visits. On the wall overlooking the gorge, an elegant pre-revolutionary Russian cursive engraving reads the surname Pemov [Пемовъ]. The stone’s deeply carved letters reflect the author’s determination to leave a historical imprint. Below, someone had carved a heart shape in tentative lines barely scratching the surface. Whether considered vandalism or artistic expression, these marks are now an integral part of the architectural ensemble. Leaving the site, there is a sense of having encountered something eternal that continues to thrive beyond the turmoil of history. So many walked these paths before me, and many more will follow.

The Village

Emerging back into the world of the living, the road from Kobayr through the village starts with a steep stone staircase, its steps polished to a glossy sheen. Signs of human activity come in the form of small agricultural plots with clumsy do-it-yourself outbuildings scattered across the hillside. Soon, typical one- or two-story village houses made of local materials appear, featuring stone bases and walls, wooden frames, and roofs of clay tiles or metal. The tufa stone gives them a reddish hue that glows at sunset. The thick stone walls keep the interiors cool in the hot summers and retain warmth in the cold winters. Featuring numerous customizations and extensions, the houses tell stories of the evolving opportunities and rationalities of the families who inhabit them. Agricultural tools are strewn about in the yards. Dried fruits and wild herbs hang from the beams. Men make and repair things, women tend to household chores, while children and domestic animals are left to themselves. The space of the village is filled with voices and chaotic movements. The dowdy unorderly structures vibrant with life cannot differ more from the elegant but abandoned monastery complex.

Arpine

One of the first houses on the route down from Kobayr is Arpine’s. During the warmer seasons, her gates remain open, and the table outside is covered by a plastic white cloth. Once someone comes in, Arpine swiftly greets them.

I have always admired the image of her walking down the stairs. Arpine, a statuesque, tall woman in her mid-fifties, is a sight to behold. Her slightly curly, long, dark hair is scattered over her shoulders. Her ankle-length floral skirt sways gently with her graceful movements. Saying hello, Arpine hurries to prepare coffee which she serves with homemade gata and fruit jams. Entertaining guests with humility in her eyes, Arpine talks of God and sings Armenian songs a cappella. On the table is a hardcover Bible. In English. This little detail is what gives her away. While the scene appears idyllic, it is not real. It is a beautiful spectacle for unkeen tourists in search of authenticity. Much like the developments described by the French philosopher Guy Debord, where being is replaced by having, and having by mere appearing. The persona of a traditional, religious village woman is a role shaped by socio-economic changes after the collapse of state socialism and inspired by proximity to Kobayr that aligns with the overall commodification of social life in the course of neoliberalism.

In reality, Arpine is a laid-off former chemist who worked at the Vanadzor chemical plant. In search of ways to sustain her family, she left her urban apartment and bought a plot of land in the village, a common example of post-Soviet crisis ruralization. Among the researchers trading cheap Turkish clothing at the market, architects sweeping the streets, teachers becoming taxi drivers –– Arpine’s new life and profession in the “hospitality industry” is not among the worst. Her flawless ability to seize opportunity and adapt to the context is commendable.

It takes some effort and creativity to get below the surface of the spectacle, but it pays off. From a humble, religious, hospitable housewife, Arpine shifts to become an emancipated cynical skeptic, skillfully navigating political debates about the future of the region and poignantly criticizing the current government. After an hour or so, when the gata is eaten, and a liter of coffee is consumed, it’s time to say goodbye and discreetly put a few thousand drams under a napkin.

The show ends, and the curtain falls.

See all [Outside In] articles here