From emerging Armenian artists across the globe to Armenian-American talent in the United States, [Art Speak] will spotlight the dynamic and diverse Armenian art world and more.

Listen to the article.

Something Joyous

Something joyous emerges from Nina Katchadourian’s work and her attempts to give secondary or alternative meanings to already extant things. Katchadourian creates fascinating new taxonomies for everyday objects, as in her re-ordering of book titles in her acclaimed Sorted Book series. Begun in 1993, this ongoing project included the well-received 2023 exhibition, “Uncommon Denominator: Nina Katchadourian, at the Morgan” in New York City. Like a minor deity, Katchadourian has taken it upon herself to put a bit of much-needed order into this world and to highlight the otherwise overlooked. The impulse comes perhaps from a desire to both understand and explain. From rocks and animals to paranormal postcards and nightgowns, Katchadourian orders, sorts, classifies, organizes and rearranges the world as she sees and understands it. At times this Linnaean drive seems almost phylogenic in impulse. Were it not for her use of humor, one might view Katchadourian’s different series as takes on The Theory of Everything (ToE). This is perhaps a grandiose claim on my part. At the very least, the artist fascinates any curious viewer. But along with the anthropologist and the philosopher, Katchadourian the artist, poses probing questions about the world by looking at the everyday or humdrum. In the process, she creates a fantastical alternate universe and points out the sometimes-arbitrary nature of how we see and classify the world around us, in an uncanny display of curiosity and creativity.

In The Nightgown Pictures, Katchadourian presents photographs taken by her grandmother of her mother wearing the same handmade nightgown over the years as she grows up in Finland. The photographs are accompanied by written descriptions by the artist of where each photo was taken, with details about surrounding landscapes and locations. The series becomes a study in both family history and local geology and architecture, as well as a document of her mother Stina’s physiological growth. It reminds one of stopping in a hotel or staying at a friend’s guest house and trying to reconstitute the family histories that one finds in pictures on walls and tables. In another fascinating project The Genealogy of the Supermarket, the artist creates genealogical narratives for imaginary people represented on food labels at her local supermarket, coyly deconstructing our obsession with family trees and origins.

In a recent meeting at the artist’s Gowanus studio, Katchadourian alluded to the fact that an interest in taxonomy runs in her family: “My grandfather was a keen observer of birds on family property in Finland. He noted how many eggs they laid, for example. He diligently observed and kept track of them, and organized his findings: which birdhouses were occupied, which ones had nests, how many eggs were laid, and how many eggs hatched.” Katchadourian is however clear-headed about her own classifying enterprise: “I think categories are worth interrogating, and that complicating existent categories we have determined is a worthwhile pursuit. To think that this belongs here, or that belongs there is a relative concept—while I believe that they are important, I also recognize that categories as we know them are somewhat arbitrary.”

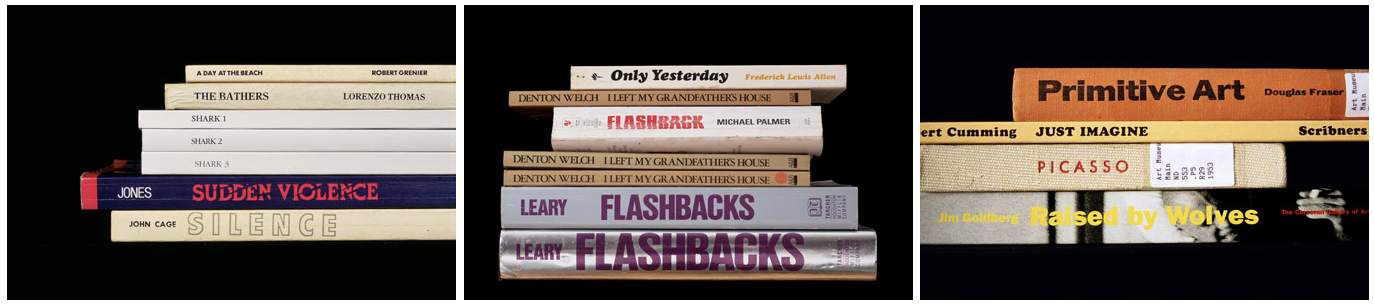

Sorted Books

Sorted Books is Katchadourian’s longest running ongoing project. Begun in 1993, it has taken place at different sites over the years, ranging from private homes to specialized book collections. However, the process for composing the photographs, Katchadourian explains, remains the same in every case: “I sort through a collection of books, pull particular titles, and eventually group the books into clusters so that the titles can be read in sequence…The Sorted Books project is an ongoing project which I add to almost each year, with hundreds of images in the ongoing archive to date.” Sorted Books subtly comments on the way things are signified and how we interpret them. Books are usually seen within an isolated context, i.e. on a book shop table, or in a library where things are listed alphabetically. Here through a clever slippage, the original meaning or signification that we associate with them now takes on secondary and tertiary meanings. These meanings create fascinating new commentaries on the books themselves and their titles: “I am often trying to shift the author’s intended meaning of a title by putting it ‘into conversation’ with a different title, or into a narrative that makes each title mean something different from what it meant in its original context.”

Taken at face value or otherwise, the work produced is both challenging and whimsical. While there are different theories of humor, “relief theory” dates as far back to Aristotle’s Poetics, where the philosopher suggests that humor is one way that human beings release pent-up emotions that may have been triggered by trauma or tragedy. As Katchadourian explained, her process is remarkably detailed: after she finds a book she writes the titles onto note cards and arranges the titles on the cards to figure out the phrases she wants to compose, culling the work that the viewer sees from these meticulously kept records: “This work is really about finding different valences of what the individual words within titles or a title phrase might mean or imply.” When she explained her process to me, I was reminded of the queen of American comedy Joan Rivers, who always appeared to be spontaneously funny, but in reality, she indexed, filed and cross-filed literally thousands of jokes by topic, content, punch line and type of joke. The level of detail talks to the seriousness of purpose and thought behind Katchadourian’s work.

Sorted Books project

Left to right: “Sorting Shark” series, A Day at the Beach; “Kansas Cut-Up” series, Only Yesterday; “Akron Stacks” series, Primitive Art. Images from the artist’s website.

Accent Elimination

In her 2005 six-channel video piece Accent Elimination, Katchadourian attempts to pull off a fascinating and offbeat experiment: to see if she can change or erase her parents’ accents when they speak English. Though they had lived in the United States for over forty years when Katchadourian created this piece, her parents still possessed noticeable and hard-to-place accents. Like Katchadourian, both my parents were foreign-born and never quite lost their accents, so I was immediately drawn to this premise. Katchadourian’s father is Armenian but was born in Lebanon, so he grew up speaking Arabic and Armenian, as well as French and English. The artist’s mother is Finnish but was born into that country’s Swedish-speaking minority. This duality in both their linguistic backgrounds adds to the piece’s uniqueness. As Katchadourian writes: “Inspired by posters for advertising courses in Accent Elimination I worked with my parents and a professional speech improvement coach intensively for several weeks, to ‘neutralize’ my parents’ accents and then teach each of them to me.” The video first records all three of the Katchadourians speaking in their natural accents, and at the end in their so-called “reversed” accents. Throughout the video, words are repeated so that the listener can best grasp the nuances of sounds and how they are “(mis)” pronounced. This last twist increases the video’s complexity and calls into question notions of identity, assimilation—and self-effacement—in the case of those people who are unduly self-conscious of their accents: “In the video, my parents and I struggle to hear and imitate what is so close at hand and yet so difficult to access. The accent is treated very literally, like an heirloom, and the project illustrates the awkward attempt to concretely transfer this ultimately culturally determined attribute.” Accent Elimination was included at the 2015 Venice Biennale in the Armenian pavilion, curated by Adelina Çuburian von Furstenberg, which won the Golden Lion for Best National Participation.

Seat Assignment/Lavatory Self-Portraits in the Flemish Style

My favorite work within Katchadourian’s already prodigious artistic output may well be Seat Assignment, which consists of photographs, video, and digital images all made while in flight using only a camera phone. Katchadourian relates that on a transatlantic flight one day, she found herself bored and in the plane’s lavatory, so she decided to spontaneously put a tissue paper toilet seat cover over her head and fashioned the result into the likeness of a 15th-century Flemish portrait. She repeated the process throughout the flight and voilà—she had created Lavatory Self-Portraits in the Flemish Style. These male and female portraits of every age are part of a much vaster ongoing project, mostly made from Katchadourian’s plane seat: “They are just one of many experiments with a methodology (what can I make with only what is already here) and the constraints of a site (the airplane), the constraints of a time-space (in flight), the constraints of a tool (the cellphone).”

She exhibited the lavatory portraits at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery in New Zealand in faux-historical frames and hung on a deep red wall, as in museums like the Louvre and the Met. In this case, Katchadourian’s hilarious send-up falls into the category of incongruous/juxtaposition theory, i.e. representations that go against normative expectations. Here the incongruity lies both in Katchadourian’s process, and in the result itself. This series of work takes on a wry twist of the imagination on the artist’s part, but also a certain sense of self-referential irony. It also calls into question the very notion of representation and dasein: who is the woman in the picture? If we believe her to be a “real” person then, is she? An added layer to the representational puzzle is added here by the fact that unlike Cindy Sherman who many people now recognize in her photographs, Katchadourian still limns the boundary between public and private figure. If we do know it is her, or if we read the exhibition wall text, then this almost heraldic mise en abyme adds another level of intimacy between Katchadourian and the viewer. The fact that her facial features differ from the prototypically demure Flemish adolescent girl adds another subtle level of irony to the photographs.

The latest studies on neocortical development by neurologist Jeff Hawkins, suggest that the brain doesn’t work like a classic computer on an input-output model as previously thought, but rather it predicts how an image or object will form based on previous experience. This is in a sense what gives any image of an actor in costume for example—or Katchadourian dressed as a Flemish girl—its eerie quality. Even after processing the original visual information, the brain must search and match the image to previous ones it may know of both women, artists and 15th century Flemish portraits that it has previously encountered. Baudrillardian notions of simulacra also come into play here, positing as they do that the media and its colleague industries like the art world have created a simulated version of the world so pervasive now that most no longer know how to distinguish between reality and unreality. As Baudrillard might have written, Katchadourian’s work here enters the realm of the hyperreal. As for Katchadourian, the artist has a more Plain English, prosaic take on her use of humor: “It’s important because it is part of a strategy to warmly invite people to come close to the work.”

Fake Plants

Most recently, Katchadourian has been at work fashioning exotic-looking plants and flowers (fungi, cacti, orchids) from factory-discarded materials in her Gowanus studio. Other previously made pieces use cast-off materials from her home and studio, or sometimes a local construction site she used to “pilfer.” These creations depict the boundary between real and unreal, artificial and natural. She uses paper pulp, carrot colored webbing and toilet paper tubes wrapped in crepe paper, as well as pieces of felt, ping pong balls and hand-colored tips. Crafted both here and in her Berlin studio, the pieces look deceptively easy but require several weeks of work. Katchadourian has already exhibited some of them at Pace Gallery in their Hong Kong and East Hampton spaces. Art sometimes imitates life, although in this case it may even have improved on it. “Natural?” Katchadourian pauses and points to a few of the fake plants: “Where does their nutrition come from? There’s something a bit creepy about these pieces.” Many of the pieces currently in her studio will be on display starting next fall at The Hyde Collection in Glens Falls, New York. They will make strange if fun artistic bedfellows to a superb collection of works that includes works by El Greco, Degas and Renoir—all housed in a stunning mansion which includes several large glass domes.

Art and Politics

The political nature of some of Katchadourian’s work may not seem obvious at first glance, but it is often present along with the more obvious meanings of some of her transformations. Her 2009 Monument to the Unelected, for example, is very much about politics. Based on signs that she saw in Scottsdale, Arizona Katchadourian created a clever series of 56 signs advertising the presidential campaigns of every person who ever ran for president and lost, or as she puts it “(our) country’s collective political road not taken.” Not surprisingly given her own genealogy, no issue seems more important to her at the moment than genocide: “Genocide is personal to me,” says Katchadourian. “My grandparents took in a genocide survivor by the name of Lucy who had been placed in a Danish orphanage in Jbeil near Byblos, Lebanon. Her entire family had been murdered. She raised my father, and to me, she was like a third grandmother.” Katchadourian also makes a direct link between censorship and genocide: “Free speech is in a terrible place, both in the United States and in Germany, the two countries I live between at present. I’ve been deeply troubled by the responses by the administration at NYU, where I teach. The lack of an effective response to the genocide currently occurring in Gaza and what happened in Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenians in 2020 are both appalling.” Regarding Germany today, she describes a poisonous atmosphere in the cultural sphere and the country at large: “Many artists I know have been supercancelled for speaking out about Gaza. In fact, I know artists, teachers and writers with families who are Holocaust survivors, and they have been called ‘antisemitic’ for opposing genocide. Funding for arts organizations is now contingent on agreeing to the IHRA definition of antisemitism, which conflates anti-Zionism and antisemitism. It beggars belief.” She expresses surprise and dismay that more Armenians in the United States don’t seem to draw parallels between their own histories and the ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people. “You’d think that understanding the terrible legacies of a genocide would create a feeling of solidarity with what is happening in Gaza now, and the desire to raise a unified voice to oppose it—after all, it’s the United States that is funding this—but it’s been remarkably, terribly silent.”

Upcoming

Apart from the exhibition at the Hyde Gallery, Katchadourian is also busy preparing for another upcoming exhibition which opens in June at the National Nordic Museum in Seattle: “This show is about my Nordic heritage,” explains Katchadourian, “and about stories that circulate within families—sometimes my own, sometimes those of others.” Titled “Origin Stories” the exhibition will include Accent Elimination, a 2026 film called The Recarcassing Ceremony, Katchadourian’s 2021 installation To Feel Something That Was Not of this World and a new bronze sculpture, Talla. After a lively exchange of over an hour, our conversation comes to a natural conclusion. Katchadourian politely avers: “Thanks for coming today Christopher and engaging with me. Art is a conversation, after all.”

Learn more about Nina Katchadourian: www.ninakatchadourian.com

Christopher Atamian

Sleight of Hand: Choghakate Kazarian and the Magical Art of Curating

Choghakate Kazarian, an Armenian-born, Paris-raised curator, masterfully blends intellectual rigor and artistic elegance. Specializing in modern and contemporary art, her groundbreaking exhibitions, from Chloé’s fashion history to Armenian abstraction, showcase her dedication to preserving and redefining art’s narrative.

Read moreMeri Karapetyan: Ready for Her Closeup at the Biennale de Lyon

An emerging artist raised in Yerevan, Meri Karapetyan challenges ideas of borders and conflict in her work, reimagining them as transitional spaces. Her large-scale barbed wire installation at the Biennale de Lyon transforms barriers into pathways, inviting new perspectives on division and identity.

Read more