Armenia’s scientific ecosystem has seen unprecedented activity in the past 1.5 years. The Gituzh initiative, launched by Armenia’s high tech and business communities, advocates for more bold allocation to promote the development of Armenia’s science and R&D to a higher level over the coming decades. It also aims to provide ample scope for cutting-edge research and consequently harness innovation for the country’s added value creation prospects.

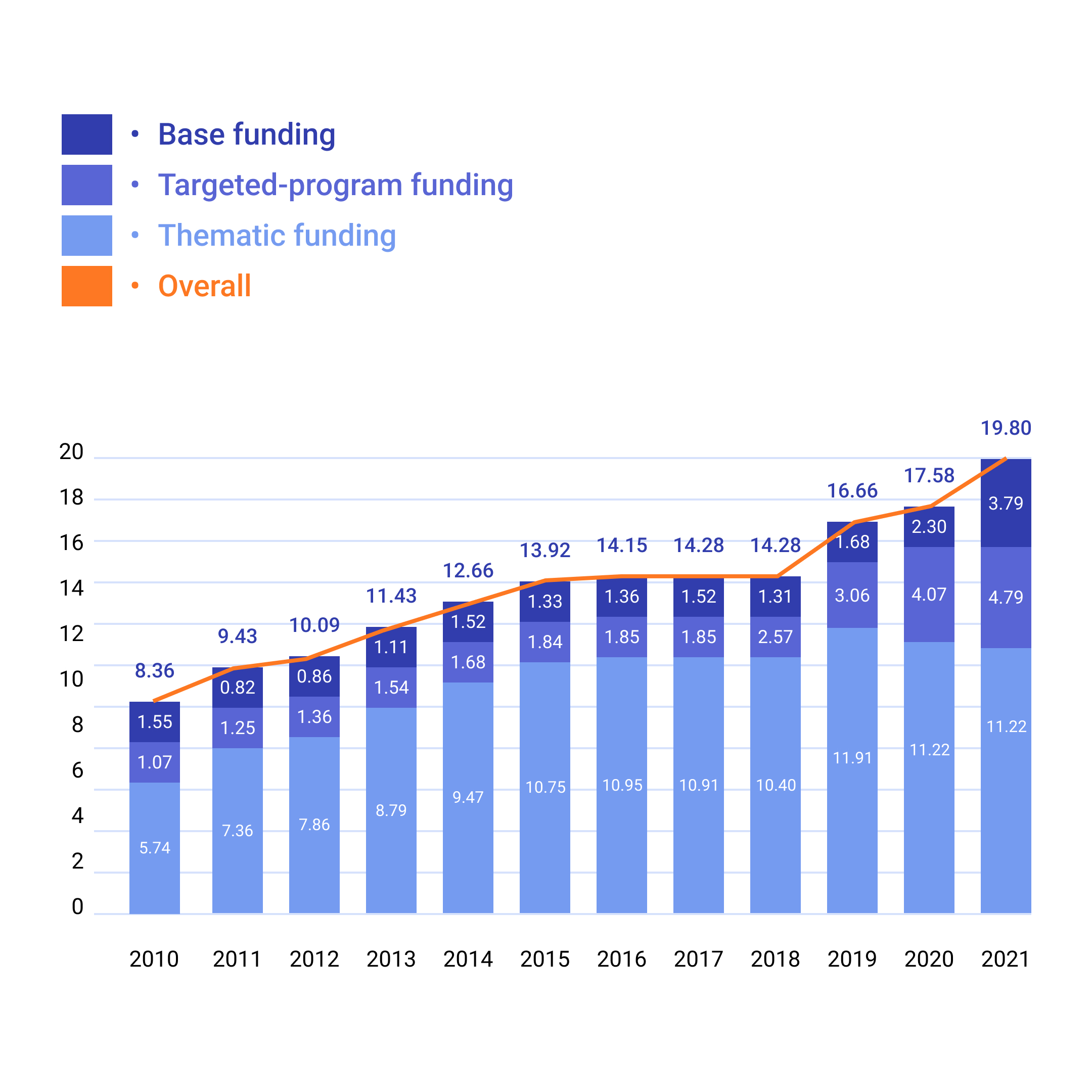

The Government of Armenia has increased the budget for science by 2 billion AMD in the last year, and the 2022 budget envisaged another 10 billion AMD increase. The total budget for science for 2022 is 25 billion AMD.

The increased funds made it possible for the Science Committee of the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports to launch two programs with the vision to bring in internationally competitive scientists with a proven track record, to consequently create a large pool of young researchers, redefine culture and environment, and strengthen the whole national science infrastructure.

This is indeed an unprecedented move from the Armenian government, however, not proportionate to the challenges Armenia’s science sector faces against the backdrop of 30 years of downturn.

The overall problem is largely the crumbling scientific ecosystem and uncompetitive infrastructure coupled with a small and aging base of scientists, including the absence of a conducive policy environment.

Disregarded and underfunded for decades, the scientific ecosystem in Armenia, as a result, is ill-equipped to cope with the multi-layered challenges the country faces. Meanwhile, the nations that prevail in a soaring global economy are those whose high technology and intellectual strength thrive. Unfortunately, Armenia faces an enormous gap between desire and achievement, and the question is what can be done to close it?

The Government’s intention to increase investment in the science base and substantially fill the giant void that has been formed at all levels following independence is a Herculean task.

The robust scientific infrastructure that Armenia once enjoyed in the Soviet era, has turned into a dilapidated structure, in part as a result of obsolescence, and in part neglect. While to compete globally across various disciplines researchers and the industry itself need ongoing access to quality infrastructure as a crucial element for making new discoveries and stimulating innovation.

Infrastructure upgrade is not confined to identifying priority areas and funding, nor is it a goal in itself. The key is boosting collaboration with interconnected networks of institutions, the number of international research teams, and co-authored publications that globally shape science and technology. Scientific collaboration leads to scientific competition. In this regard, the potential of the diaspora has already proven to be of immeasurable value. It was due to the large wave of repatriates in the 1940s that brought diverse talents that Soviet Armenia once thrived as a science and technology hub with labs and institutions of global significance and competed in the global arena. And now more than ever, Armenia is in dire need to switch from the social practice of a “brain drain” to a “brain gain” amid the rapidly diminishing scientific milieu.

The number of researchers involved in state-funded programs is roughly 3500; of those, 2500 have PhDs, and 1000 are older than 65. This number keeps decreasing by around 200 every year, according to Gituzh initiative estimates.

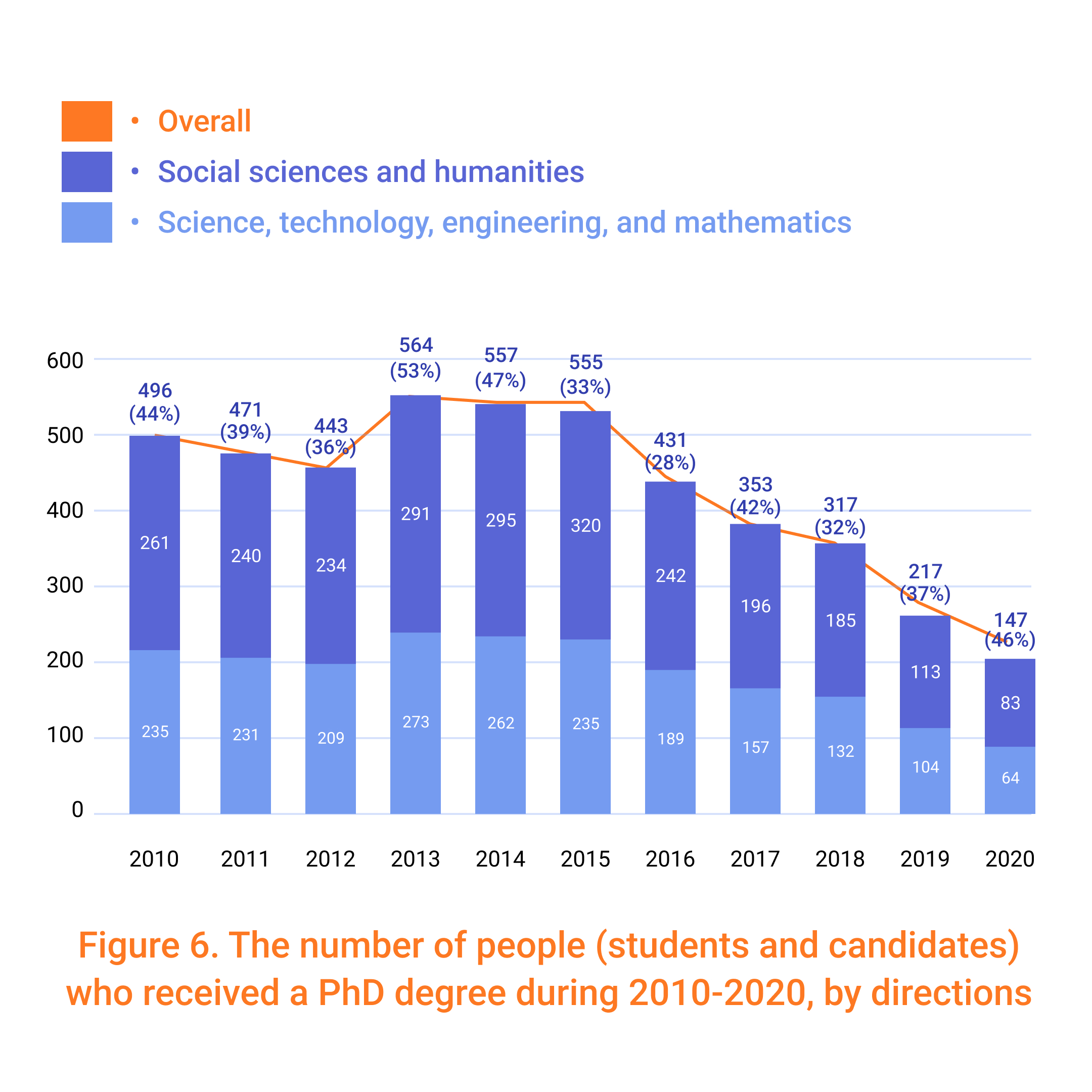

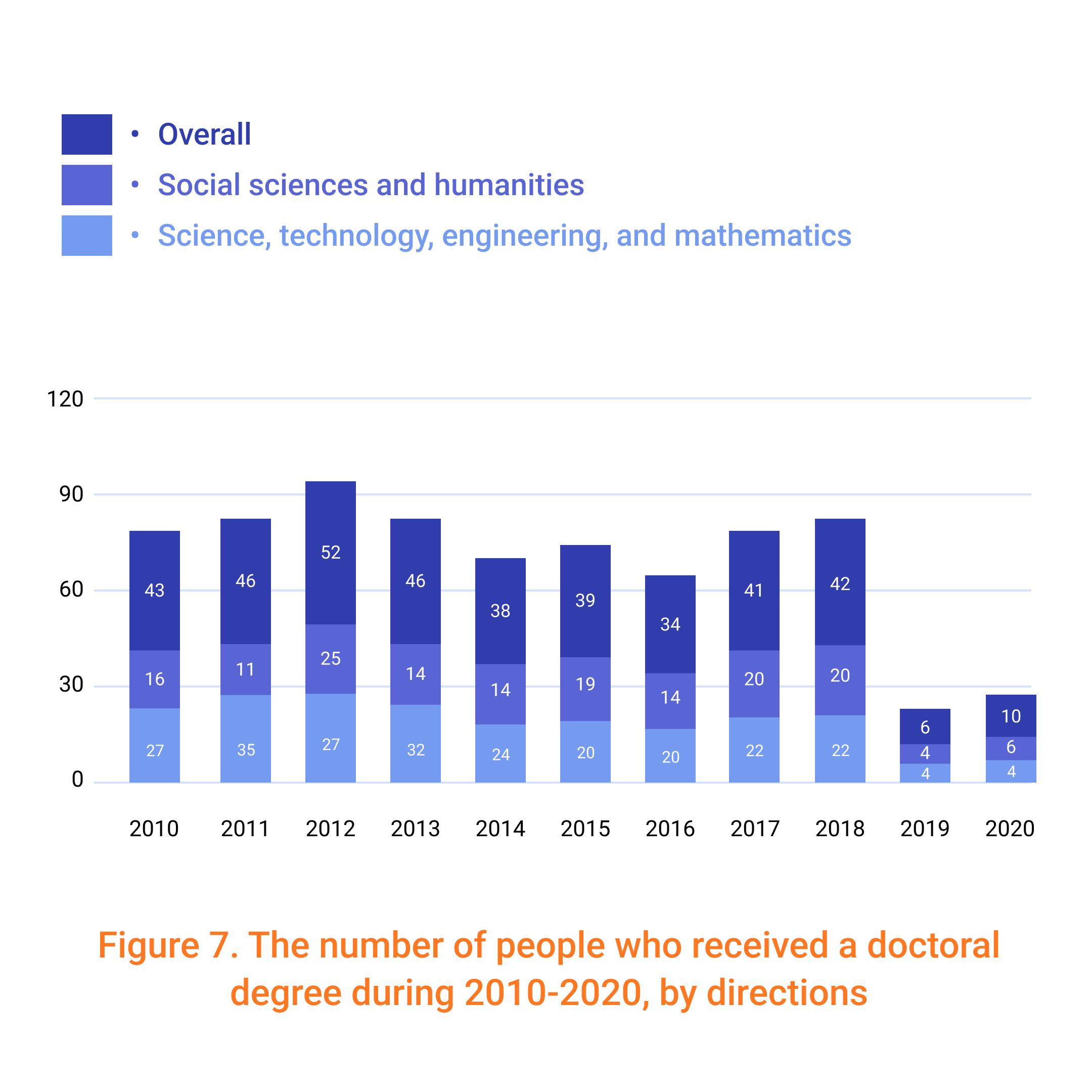

The benchmarking statistics in Figures 6 and 7 reveal the stark reality regarding the nosedive trend in the number of researchers between 2010-2020. While in 2010, the number of PhDs received in the humanities and natural sciences and engineering is respectively 261 and 235, that figure dramatically plunges by 2020 hitting 83 and 64 in those fields. The same trend is in place regarding postdoctoral degrees: four as opposed to 27 and six as opposed to 16 in the same time period.

Artur Movsisyan, a deputy chair of the Science Committee says that two programs have been launched to address these problems: integration of foreign scientists into the Armenian scientific space, which in turn has two components – LAURIK and CARIN. In fact, this is a call for relatively young and mid-career researchers. The other program, ARPI, targets researchers, professors, and tenured professors or equivalent positions in order to establish and lead remote labs in competitive fields. These programs are groundbreaking for Armenia in terms of the proposed grant amount, and the concept of targeting scientists from abroad—Armenian or non-Armenian—and enabling them to continue their scientific careers in Armenia.

Such criteria account for the gaps existing in Armenia’s scientific potential. “We need mid-career and young scientists,” Movsisyan says. The Science Committee’s call targets that age group, while the remote lab program aims to attract experienced scientists who can form and lead labs in Armenia with young researchers. The labs will do research in competitive scientific fields. This will upgrade the existing scientific directions, and establish those that are missing or empower those that are underdeveloped, for instance, robotics. Social sciences and humanities are specifically emphasized, with the expectations being higher in those fields. They are underdeveloped, unlike many STEM directions. Hence the selection commission encourages and will emphasize applications in the humanities and social sciences.

All things considered, these are trailblazing opportunities and a bold message that Armenia is open for ambitious scientists from any part of the world who wish to relocate and pursue their research. The five-year grant provides scientists a relatively competitive salary and the opportunity to work on their projects including creating a lab, assembling a team and working on their research.

Movsisyan is confident that researchers who relocate to Armenia will find what they need. While it may not be financially competitive in some cases, the grant, specifically CARIN, provides more than adequate funding to lead a comfortable life in Armenia. It not only enables researchers to set up and lead a lab or a research group, it provides opportunities to apply for other international grants. Finding a job as a researcher is a tough task in many developed countries due to stiff competition, not to mention a lack of autonomy for individual research: these programs provide both.

A pivotal factor must be considered, however. The basic underpinnings of the programs are the enhancement of capabilities of the country’s economic, educational and social spheres by promoting scientific capacity and excellence for sustainable development. Therefore, applications that will tackle areas that are poorly developed or non-existent in Armenia and may in the future be among the priority areas of scientific development, will be given priority. Building a robust scientific base is not only about transferring knowledge and instrumentation; rather such efforts must be tied to national needs to rebuild trust and serve society in the long term. As Movsisyan stresses, the concept of socio-economic impact “assumes that investing in the scientific system yields results in social, economic, educational and all other spheres.”

Science alone is not a magic bullet, but the key to scientific success resides in human resources. The road to the robust scientific ecosystem that existed in the Soviet era was paved in a similar way, according to Movsisyan. In retrospect, institutes and strong scientific groups were formed with key people returning to Armenia, among them astronomer Victor Ambartsumian, physiologist Leon Orbeli and the physicist Alikhanyan brothers. They came from Russian and European scientific institutes that produced Nobel Prize laureates and nominees. “Our solid ties with the Diaspora resulted in those international collaborations. Now we are trying to restore that tradition,” Movsisyan explains. The new blood and fresh ideas that come with it are a real chance to improve the environment, bringing into fruition a culture change in Armenian universities, by promoting far deeper and more widespread engagement, improving the quality of education, and making science an attractive field for school children. Postgraduate students will also benefit from having qualified academic supervisors. The results of such efforts, coupled with work underway to boost the infrastructure, create centers of excellence, and provide international training for staff, will unfold in a snowball effect.

Hrant Khachatryan, the director of YerevaNN, a machine learning research lab, thinks that one of the firmly embedded problems in Armenia is the quantity and quality of young and mid-career researchers. “These calls by the Science Committee are the most targeted programs ever, and will enable scientists working in other countries to be involved in the scientific ecosystem of Armenia, consequently rejuvenating it,” Khachatryan explains. This initiative can have a profound impact, and if carried out on a larger scale, will not only redefine science in Armenia but also reshape standards and tackle the need for significant cultural adjustments in the system.

Khachatryan is certain that if these efforts were tripled, combined with the repatriation programs, it would sound like a much more serious commitment and would attract tenured scientists, especially bearing in mind the opportunities that the larger regional setting opens up. He does, however, note the difficulties in communicating and disseminating information; that is, ensuring that a scientist who is eligible, is aware of this opportunity early on, and has confidence in the process.

According to Khachatryan, even more unsettling is the bureaucracy and management style of academic institutions. They are slow-moving and not proactive. As of now, the universities in question are dragging their feet over pinpointing potential applicants in their networks even though the deadline for one of the programs is fast approaching. Bureaucratic practices and disruptive policies regulating research should be eradicated, he says.

The Gituzh community, for their part, reaffirm their commitment to supporting the advancement of the scientific ecosystem and as such, university professors and scientists working at institutes who are trying to slow the process down for any undue set of reasons, will not be tolerated.

Tigran Shahverdyan, a member of the Gituzh initiative, believes that there are two ways to stave off the current trend of degradation of the scientific community: with internal sources, i.e. young people receiving their PhD and joining the scientific community, and the emmigration of scientists from abroad. “The first one is a time-consuming process,” he says. “The required changes won’t happen overnight. It will take several years until we increase the number of PhD students in the country. The second one can happen faster with required investments in place.” Making it happen and making it happen faster is vital, he adds. “The hard-hitting fact is that there is no other way to empower Armenia against its challenges.”

“And for our fellows in the diaspora, these programs are an opportunity to be the next flagbearer of that cause by making the decision to pursue an academic career in Armenia,” Shahverdyan says. He encourages the scientific community to give constructive feedback, criticize, get involved, and contribute to the further expansion of the programs. “Their engagement will facilitate the advent of new programs coming to fruition, more ambitious targets, and the allocation of relevant funds,” he says.

To address the dangers and crises that are rapidly proliferating at Armenia’s doorstep, wider-reaching programs are needed. They will be achieved when the environment is shaped, young and mid-career scientists sign-up, and infrastructure is put into place. This is eventually going to happen. It always takes one small step to make a series of bigger leaps.

“The Government of Armenia has increased the budget for science by 2 billion AMD in the last year, and the 2022 budget envisaged another 10 billion AMD increase. The total budget for science for 2022 is 25 billion AMD.”….It would be instructive to know these amounts in US dollars. Who does the editing for EVN?