Tensions between Iran and the West have received some airtime domestically in Armenia, but the topic is under more scrutiny in international circles. In order to deduce possible repercussions of the escalation of this new hostility on the Armenia-Iran economic relationship, a brief review of recent international relations is in order. Those familiar with the recent dynamics between the West and Iran can fast forward to the second part of this article.

Background: Recent Developments in Iran and Western Relations

Relations between the U.S. and Iran have been strained for decades. Their origins trace back to the 1979 hostage-taking of Americans during the Iranian Revolution (and, in fact, even further to the nationalization of Iran’s oil industry by then Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh and the subsequent 1953 CIA-organized coup against him). In the mid-2000s, further pressure was brought to bear through sanctions via the UN Security Council Resolutions (UNSCR) that specifically pointed to Iran’s nuclear programs and their possible military application. Iran denied that any of its operations were targeting military applications and insisted that it was a matter of national sovereignty to develop civilian, energy-related nuclear capabilities. In any event, this wave of sanctions targeted suppliers of nuclear inputs and related equipment, as well as asset freezes abroad.

Sanctions were further tightened at the end of that decade with hurdles put on the international activities of Iranian financial institutions. Moreover, naval operations were made more cumbersome with further regulations. That round of UNSCR penalties was said to be motivated by Iran’s ballistic missile programs.

By 2013, the economic impact of these measures was becoming apparent: these concerted efforts had made it significantly harder for Iran to export its oil. As a result, proceeds from oil and gas exports halved between 2011 and 2013. Given the reliance of the economy and state budget on oil revenues, broader effects became visible. Diminished access to U.S. dollars via the banking system as well as from oil revenues led to the depreciation of the domestic currency rate on the black market from some 10,000 rials per 1 USD to 25,000 – a dramatic move by any standards and notwithstanding stable oil prices during that period. This fed into an inflation rate of 40 percent in 2013.

By 2015 though, tensions subsided. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) agreement, also known as the Iran Deal, was reached between Iran and the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (plus Germany). Under the accord, Iran agreed to meaningfully scale back its nuclear activity and allow in international inspectors in return for the lifting of all nuclear-related economic sanctions that would free up tens of billions of dollars in oil revenues and frozen assets. Oil exports rebounded to pre-sanction levels and economic stress decreased.

Broad optimism, both domestically and in the international community, on prospects for the Iranian economy ensued. There were discussions on how to tap into this new developing market opportunity of 74 million (with a GDP/capita of 5600 USD compared to Armenia’s 4200 USD). The Islamic Republic, long being cut off from necessary investment in machinery to revitalize everything from its Boeing fleet to oil producing equipment and car production lines, seemed to offer much to look forward to. Oil prices at still elevated levels and above $100/barrel boosted Iranian purchasing power accordingly. The economy even weathered the 2014-2015 collapse in oil prices.

Nevertheless, the optimism proved to be fleeting. By 2016, U.S. Republican Party primaries revealed skepticism about the 2015 deal negotiated by the previous administration. The leading candidate, Donald J. Trump, was especially resolute. As a result, many European and American corporations became quite hesitant to commit themselves to investments and transactions with the Islamic Republic. Banks in particular were hesitant. After the recession of 2008-2009, they had come under heavy scrutiny and charged billions of dollars in fines. Understandably, they were most reluctant to go against political currents. And, of course, without banking channels, oil revenues were difficult to collect.

The incoming Trump administration expressed several grievances. Firstly, they viewed JCPOA as too lenient. Iran’s financial maneuverability had increased dramatically while restrictions on their ballistic missile program and nuclear activities were not strong enough. Iran could presumably just “wait it out” and freeze its operations as opposed to fully discharging them while JCPOA was in force (a 15 year duration). In addition, this new economic strength had ostensibly facilitated the spread of Iran’s influence across the Middle East in places like Syria, Lebanon, Yemen and Iraq, further upsetting the regional status quo and drawing alarm from traditional U.S. allies like Saudi Arabia and Israel. As a result, the White House withdrew from JCPOA in May 2018, re-imposed sanctions and pressured the EU and other allies to substantially decrease or eliminate oil imports from Iran. The depreciation pressure on the rial resumed and it has fallen 60 percent since. (While inflationary, this dynamic increased the competitiveness of Iranian non-oil exports, an effect the IMF had already drawn attention to during the first round of rial weakness in 2013).

Iran expressed disappointment and frustration. It had complied with the agreements reached and viewed U.S. actions as unwarranted, unfair and undermining goodwill in any potential future negotiations. The nation had made meaningful sacrifices only to face reneging counterparts and investment benefits that never materialized. Europeans tried to salvage what was possible from the deal and keep Iran adhering to previously made JCPOA commitments.

This state of events most recently escalated to the retaliatory, and somewhat theatrical, seizures of Iranian and British oil tankers.

Understanding Armenian-Iranian Relations – Any Prospects for Change?

Before moving forward, a few points on the current state of events and economic interactions are in order. Unfortunately, public data, statistical or otherwise, is limited, making detailed repercussions difficult to project.

Economic relations between any two nations can be divided into several channels. Firstly, there is the obvious flow of trade of goods and services (including tourism). Then, there is labor migration and concurrent transfer flows. Thirdly, there’s the investment flow across the border. Finally, there are banking credit and transactions.

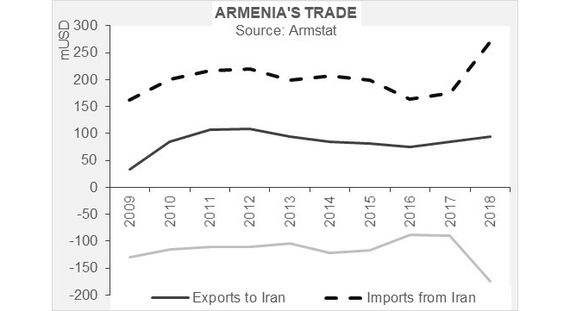

Iran is Armenia’s fifth largest trading partner (360 million USD annual turnover for 2018, which saw a notable jump in Iranian imports). Moreover, Armenia has run a continuous trade deficit with Iran of approximately 90-175 million USD per annum. While a detailed breakdown per goods category is not available, a major share of those totals are gas purchases by Armenia that are converted into electricity and sold back to Iran in aggregate to the tune of 60 million USD.

If one studies the last decade of trade, and looks through the 2018 spike, turnover has continuously decreased. In 2017, it was down some 40 percent from its peak in 2012. Both exports and imports had declined. And while there was some excitement also in Armenia when JCPOA was signed, no notable trade improvement was registered during 2015-2017. Maybe this was of little surprise: post-JCPOA Iran was in more need of machinery and equipment to update and upgrade its industrial capacity and less interested in what Armenia had to offer.

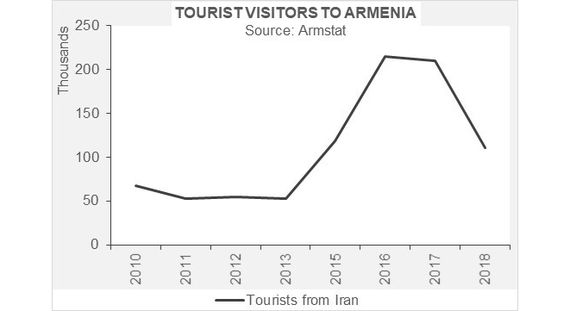

One place that actually saw some impact from the sanctions relief was tourism. There was a meaningful acceleration after JCPOA. The number of visitors then almost halved from their peak in 2017, even in light of the 2016 visa liberalization between the two countries. The fallback was a natural reflection of the dampened mood of Iranian households given the renewed financial difficulties and the negative news headlines of 2018-2019. Sanctioning of Iranian carrier Mahan Air’s flights to Armenia might also have contributed (international restrictions had already been initiated in 2011).

Looking forward, there are several matters that make the case for improvement in trade less than straightforward, at least outside of the energy sector and even if sanctions would be relaxed. One issue is that Iran has relatively high import tariffs. Last available data from the beginning of this decade show a number of above 15 percent average import duties. As a reference point, Armenian duties are around 4 percent, EU duties are 2-3 percent, while Eurasian Economic Union duties oscillate between 4-6 percent. Anecdotal evidence suggests that general non-tariff barriers are also an issue. In essence, Iran seems to be quite protective of its domestic markets and relies extensively on import substitution policies.

Another matter with regard to the trade outlook, and which ties back to the last point made, is the high prevalence of state owned enterprises (SOEs, by some measures, account for 50-60 percent of the economy) and a general heritage of high state involvement in the economy. Armenia being increasingly more reliant on free market dynamics and less government involvement, introduces a certain misalignment for local and Iranian businesses when it comes to business relations.

Thirdly, while some sectors of the Iranian economy might not be sanctioned outright, during the last weeks, head of the U.S. Treasury Department made a not so subtle remark that any company will have to choose to either operate in the Iranian market or the U.S. one. While this might seem irrelevant for a small company not selling into the U.S., ultimately access to USD transactions and USD savings could be restricted for that same firm in the worst case scenario, further raising the cost-benefit calculations of operating in the Iranian market. (There has been speculation that transactions could be done in local currencies, but then the question becomes what should an entity do with their AMD or rial business sourced receipts in hand? Most residents of developing countries prefer to save in select foreign reserve currencies and not in other currencies with less established macroeconomic and institutional underpinnings).

To summarize, at least from my vantage point, future trade with Iran is bound to be restricted mostly to energy deals made at the inter-governmental level. Whether the U.S. sanctions will restrict room for such an increase is possible but unlikely. The U.S. has granted waivers to other Iran-sourced oil importing allies before and will plausibly have some sympathy for the Armenian case. With regard to private business interactions, the outlook seems more challenging. The difference in economic models and structures, duties as well as other barriers to trade will restrict business relations, free-economic zones (like the one in Meghri) notwithstanding. Accordingly, any U.S. sanctions will likely have a restricted impact on trade flows between the two nations.

Turning towards cross-border investments and looking on to foreign direct flows into Armenia from Iran, put mildly, these have been insignificant (1.8 million USD peak in 2002). During this decade in particular, a zero in balance was registered for several years running, and even a withdrawal of Iranian capital in some cases. One caveat is that some flows could have been rerouted via offshore centers. But, even then, increased capital controls and offshore center oversight probably constrained usage of that channel as well. In other words, the Iranian economy’s specifics and energy reliance, together with Russia’s standing within Armenia’s energy and utilities sector, another outcome may have been difficult to expect.

Banking

Turning to the possibility of cross border bank activity, the prospects are even more daunting. If there could be some leniency with regards to energy flows, the prospects for liberalization of financial transactions is nearly impossible. While there is one bank in Armenia with Iranian capital, it has for years been at the bottom of rankings with regard to asset size. Its activities were further restricted in 2018 due to U.S.-imposed sanctions. In any event, the banking strength of Iranian institutions has been weakened during this past decade with significant amounts of non-performing loans still on the books and large parts of the Iranian banking system undergoing restructuring and recapitalization. Thus, it is unlikely that an Iranian parent-bank would be in any position to grant loans in hard currency for use in the Armenian economy.

Cross-border loans from Armenia to Iran would be similarly challenging. Any Armenian financial entity channeling loans into Iran would face immediate scrutiny and be potentially cut off from SWIFT and U.S. dollar transactions by U.S. authorities. These risks are as prohibitive for an Armenian entity as they have been for any other bank.

Conclusion: Direct Impacts Marginal, Indirect More Challenging Yet Improbable

To summarize, economic relations between Armenia and Iran are unlikely to see significant changes even in light of escalating tensions with the West. Recent records underline this. The former is due to several factors. Specific sectoral orientations and competitiveness (services/tech vs hydrocarbons) are one such cause. Differences in economic philosophies (market-oriented vs. state-led) and high barriers to trade (duties and non-tariff barriers) another. Armenia’s reliance on Russia as its predominant energy supplier yet another. Usually, bordering nations are each others’ largest trade and investment partners. In this case though, sanctions or not, structural impediments will unfortunately be difficult to resolve, at least in the short-to-medium term.

Finally, does this mean that the hostilities between Iran and the West are unlikely to have major repercussions on Armenia’s economic outlook? Not nearly. The largest possible downside risk for Armenia is an indirect one – with tensions in the Middle East transmitting themselves into an even weaker global business confidence, into a rise in oil prices and ultimately undermined financial stability abroad. While possible, scenarios like the 1970s oil crisis (which resulted in the price of oil rising by nearly 400 percent), inflation and recessionary bouts is still unlikely. Not least because of years of subdued inflationary outcomes internationally and because the U.S. has become a major oil producer itself.