Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

We arrived at Kilittaşı village in Turkey on the morning of October 6, 2021. Some have probably never heard of this village, but its old name Bagaran might ring a bell. It lies on the very edge of the modern Turkish-Armenian border, which is marked by the snaking currents of the Akhuryan River. The surviving Armenian natives of this village fled during the 1920 Turkish-Armenian War and established a new settlement with the same name in what became the Armenian SSR—just a few kilometres away from Kilittaşı itself. Bagaran had a continuous Armenian presence since at least the third century BC, up until the Armenian Genocide. The various kings who ruled the area initially made it the spiritual center of pagan Armenia and then, in 895, the Bagratuni King Ashot I briefly turned it into the capital of the country itself. There is a lot of history in this place, but my focus here is on our single day as outsiders, attempting to untangle the knotty heritage of this haunted locale.

The road leading to Kilittaşı is rocky and unpaved. The signboard at the entrance to the village road says that there is an ancient church in the village, but doesn’t indicate which denomination. I am sure many people pass by here without ever thinking of visiting the settlement. As we entered, we didn’t see a single soul. I was travelling with my friend, A., who is a Turkish travel blogger. As we drove around the tiny village, we caught a glimpse of Saint Shushanik Church, which lies on the Armenian side. The church is from the tenth century and has numerous legends about it. All that separated me from this church was the Akhuryan River. In summer, when the river levels drop, it is possible to walk across, but doing so would be considered an illegal entry into a sovereign territory. The thought did cross my mind, however, since I had applied in Yerevan for the necessary permits to visit the church from the Armenian side. The documents were granted and, as I made my way to the border checkpoint managed by Russian troops, I was rejected without any reason as to why.

View of St Shushanik across the Akhuryan River.

We stood at the Akhuryan, gazing at Saint Shushanik. It seemed just a stone’s throw away, but also infinitely unreachable—a condition that seems to encapsulate the Turkish-Armenian cultural-political gulf in general. I was in the area during the summer of 2019, when Kurdish children were swimming in the shallow waters of the Akhuryan. Now it is October, and no one is around. We walked further up the village to the site of the ancient Bagaran settlement. One can see the remains of structures scattered across the area and a more recent 18th-century Armenian church at the top of a rocky hill. We zigzagged through the old walls and climbed up to it. The views from up there are impressive. One can see the river and the canyon, as well as the Russian watch tower in the distance, facing the Turkish military base.

The church is missing its roof and shows signs of treasure hunters. The khachkars (cross-stones) at the front are damaged, and many people have vandalized the church by carving their names on the building. The earliest dates I could find among this graffiti were from the end of the nineteenth century, and they were messages left by Armenians. There is a signboard here, but, typical of the region, it lacks credible information, saying that it is a 10th-century Bagratuni Church, when in fact it is an 18th-century construction.

As we made our way back down through the ruins of old Bagaran and into the more recent Kurdish settlement, I saw three people sitting in front of a house, drinking tea. I asked A. to go over and ask them in Turkish what they knew about the old village. The younger man in the group was a local called Mehmet, who was enjoying his morning tea with his parents. We approached and, after a minute, joined them in the traditional tea-drinking ritual, after which we were pressed to join them for breakfast. This process would take over an hour, so Mehmet had time to tell us what he knew about the village and kindly agreed to show us around.

According to Mehmet there were once five churches here, and he pointed at the two still standing (St. Shushanik and the eighteenth-century basilica). He then took us to three other sites that seemed completely barren. Our guide went on to say that he is surprised to see people visiting this village, since the general impression the media gives is that Turkey’s deep east is rife with terrorism, which puts people off visiting. Mehmet took us to a house just a few steps from his own to show us remnants of churches and khachkars used as support stones.

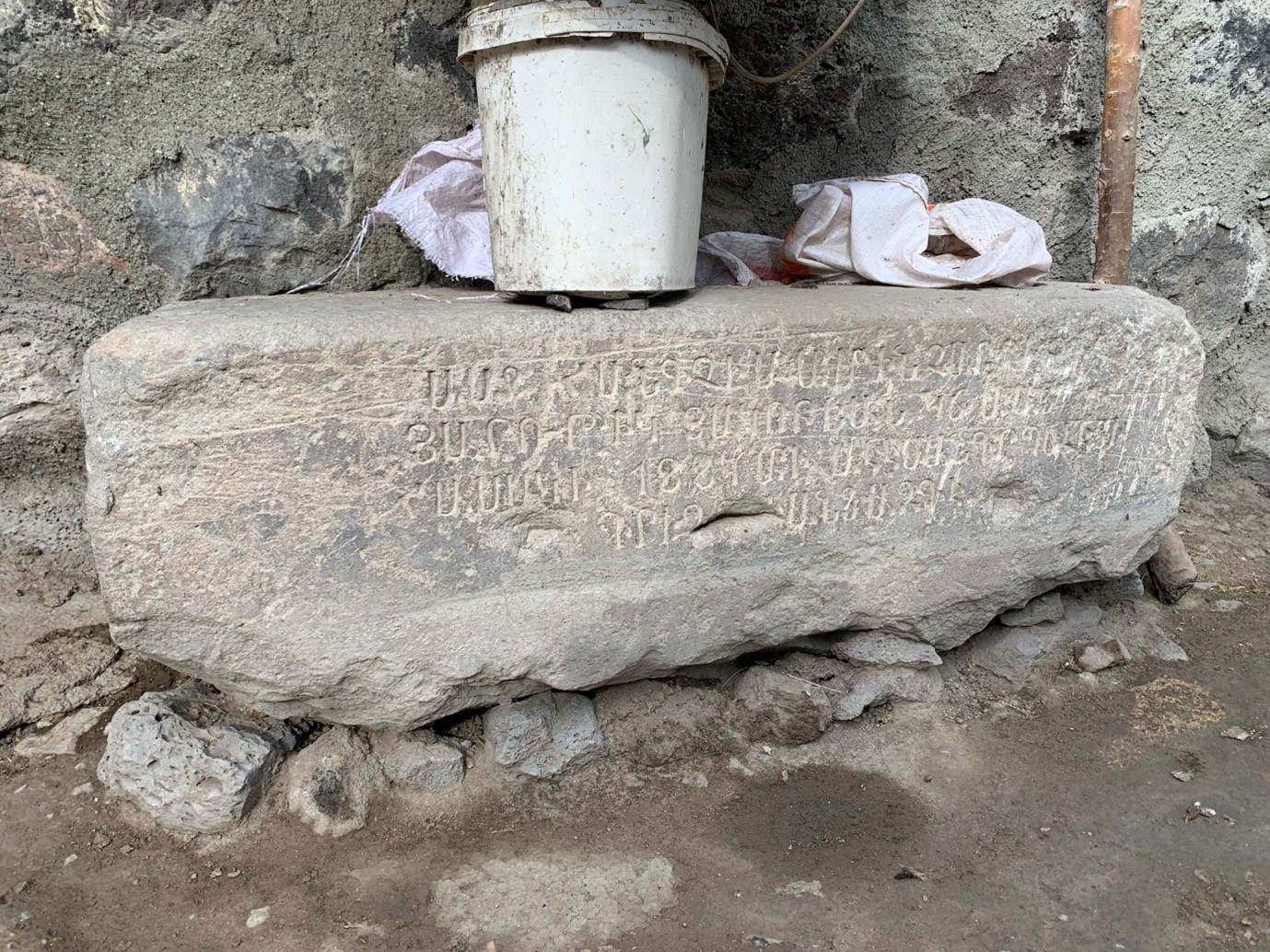

Mehmet then led us back to the old Armenian settlement, but showed us something we missed. There were two khachkars completely engulfed by rubble. Clearly, this was the location of Bagaran’s medieval Armenian cemetery. Many years ago, one could still see numerous cross-stones here but, in the last two decades, the rocks above it had gradually collapsed and covered over the site, forever hiding these irrefutable traces of Armenian presence. Back in the village, we were shown a big funerary stone from this cemetery with an Armenian inscription that was used as a bench. Repurposing such historical fragments as building material is a custom that stretches back thousands of years, and there are hundreds of villages across Anatolia whose modern-day abodes carry the vestiges of ancient Armenian and Greek monuments. The highly ornate fragments of khachkars and church pillars are often exposed on the facades of these humble village homes for their powerful decorative effect, creating a disjuncture that is at once surreal and tragic.

We were now ready for the huge breakfast that the hospitable family had prepared for us. As we ate, Mehmet’s parents waxed nostalgic about the old days and lamented the fact that all the youth had left for Istanbul. They were worried that Kilittaşı is becoming a ghost village but, to me and A., it had already become one. Mehmet told us that, every now and then, he sees Russian soldiers and some Armenians attend Saint Shushanik for rituals. He usually waves at them and says Salam. I told him next time he should shout Barev.

Toward the end of our visit, Mehmet shared two more stories. He told us how his chickens ran away from him and crossed the border up to Saint Shushanik Church, and how he comically ran across to bring his chickens back from another country. Finally, he informed us that the Turkish government has banned any new buildings in the village because, as of 2023, an archaeological team will be entering the area to begin excavations. What they will work on is a mystery, considering the predominantly Armenian heritage of this area. Before bidding our goodbyes, we tentatively asked whether there are any more Armenian traces left in the vicinity. Mehmet pointed to the other side of the village and said there is a natural spring with cross markings around. As we were leaving, I tried to give him some money for his kindness, but he adamantly refused.

We took the short drive to the other side of the village, looking for the spring and cross-stones that Mehmet had mentioned. The car couldn’t go any further, so we had to walk on foot. This is when we met a group of young children shepherding their flock. A. was speaking to them in Turkish and I was asking questions in English. One boy said he knew where the cross was and took us there. The boy’s name was Ararat. For a moment, A. and I froze and looked at each other in amazement as he pronounced his name. Does he know what the name refers to? Is he Armenian? Or is it a nice sounding name his parents picked? A. explained to him his name is the Armenian for Agri Dag (Turkish for Mount Ararat). He looked at us in confusion. I didn’t want to interrogate the poor boy anymore, and he quickly jumped up some rocks and pointed at a cross carved on one of them.

The remains of old Bagaran overlooking the new Kurdish settlement.

A 19th century funerary stone from a church used as a bench in one of the Kurdish houses.

Ararat at the spring.

The cross with inscriptions was right next to the spring. Ararat then jumped down and drank from the crystalline water of the spring. His friends were calling but, just before he dashed away, he told us to climb up and keep walking towards the abandoned military base, where we could find more things. At this point, we met the third protagonist of our short journey—Zeki Choban (meaning Wise Shepherd). Zeki lived in some isolation away from the main village, and we spotted him climbing a ladder and attending to some trees on his small farm while on our hike up the hill. We asked him some questions about the area, and that’s all it took for Zeki to leap down from the ladder, tell his wife that he will come back soon and join us in our search for Armenian heritage.

As we walked, he showed us one khachkar on the ground and then took us to a big empty area full of rubble. A. and I scratched our heads for a moment. What was Zeki showing us here? There was nothing. But Zeki insisted that there used to be an enormous church at this precise spot. I tried to recollect what I had read in a paper by one of the esteemed scholars of Armenian architecture, Christina Maranci, who has studied this region in great detail. Of course, the “ghostly” church could only have been St. Theodore—an impressive seventh-century structure that now exists only in old photographs and sketches made by Armenian architectural historians Toros Toromanian and Arshak Fetvajian. The intricately-decorated church was mostly extant up until 1923, but it was progressively destroyed and then finally blown-up by the Turkish military sometime in the 1940s-1950s. That old base is just 10 meters away from the church. Zeki told us that, in his younger days, the church was still standing, but since it was located in a military zone, soldiers, treasure hunters and mother nature had all been involved in its complete destruction. Zeki went on to say that, when the church was in pieces, locals would come to take the stones away to reuse in their homes—evidence of which we had seen ourselves.

Zeki led us to the next and final spot. There was a huge rock with multiple crosses on it. The “wise shepherd” said that the area used to be a cemetery and that, a long time ago, someone had managed to get a digger up the hill to dig up the ground. They found gold and left. Now, all we see is a very big hole with scattered bones all around. He said that, from time to time, when he cultivates his farmland, he finds human bones. Perhaps his farm is also part of this former cemetery. The last thing he mentioned was that the Kurds moved here from nearby villages after 1920. They first tried to live in the abandoned Armenian houses but, for some reason, they could not adapt, so they built their new village next to it.

We spent around five hours that day exploring the village that stands as a metaphorical manifestation of this region’s rich and tragic, but also fascinating, history. The friendly and hospitable characters we met wanted to give us as much information as possible. They were stories and tales that had passed down from their grandparents and parents, who had somehow managed to make a life for themselves on these melancholy lands soaked with the unresolved pain of historical traumas. It is as if these stories have a will of their own and, just like the Armenian name of the Kurdish boy, they perpetuate the memory of the past, despite all the attempts to forget or eradicate it.

Thank You for sharing your travel memories with us. I think it is very important to have as many acounts as posible i order to preserve historic facts because the truth matters. I have had the privilege of being part of orgenizing pilgrimages for Armenians of Iran to visit Western Armenia many times, but we have never had the chance to see Bagaran.

Good luck to you and thanks again.

Nice Article! I enjoyed reading it

Its an impressive, detailed report on the Turkish-Armenian border region. It gives the reader an impression of tragedies which shaped Anatolian soil, its wise and beautiful people. There should be more attempts like this one to explore these traces/remains of history in order to restart the Turkisch-Armenian dialog, to remember their common heritage – both sides will be winners.

The writing of Gurdeep Mattu – he seems to be a passionate researcher – is an important step towards these important and humanic goals – keep on Gurdeep!!

Truely yours – Jochen

p.s. I have visited Armenia several times, to organized a cultural event in Nuremberg, commermorating KOMITAS (including an exhibition of my fotographs, a panel together with a speaker from the Hrant Dink foundation/Istanbul and two wonderful concerts (with Karine Babajanyan, Vardan Mamokonian and may other…)

see my short video introduction https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hLHVqmvGfFM

Dear Gurdeep, thank you for the fascinating article. I didn’t have a chance to see the Bagaran in Armavir but heard a lot about it on our way to Argishtikhinli, one of the Urartian fortresses that is on Armenian side in Nor Armavir, not far from Bagaran. The area has layers of history from ancient, pre Urartian, Urartian, post Urartian, many centuries of Armenian heritage. Unfortunately lack of funding and proximity to the border are major barriers. It is interesting, though, that Turkey is planning excavations.