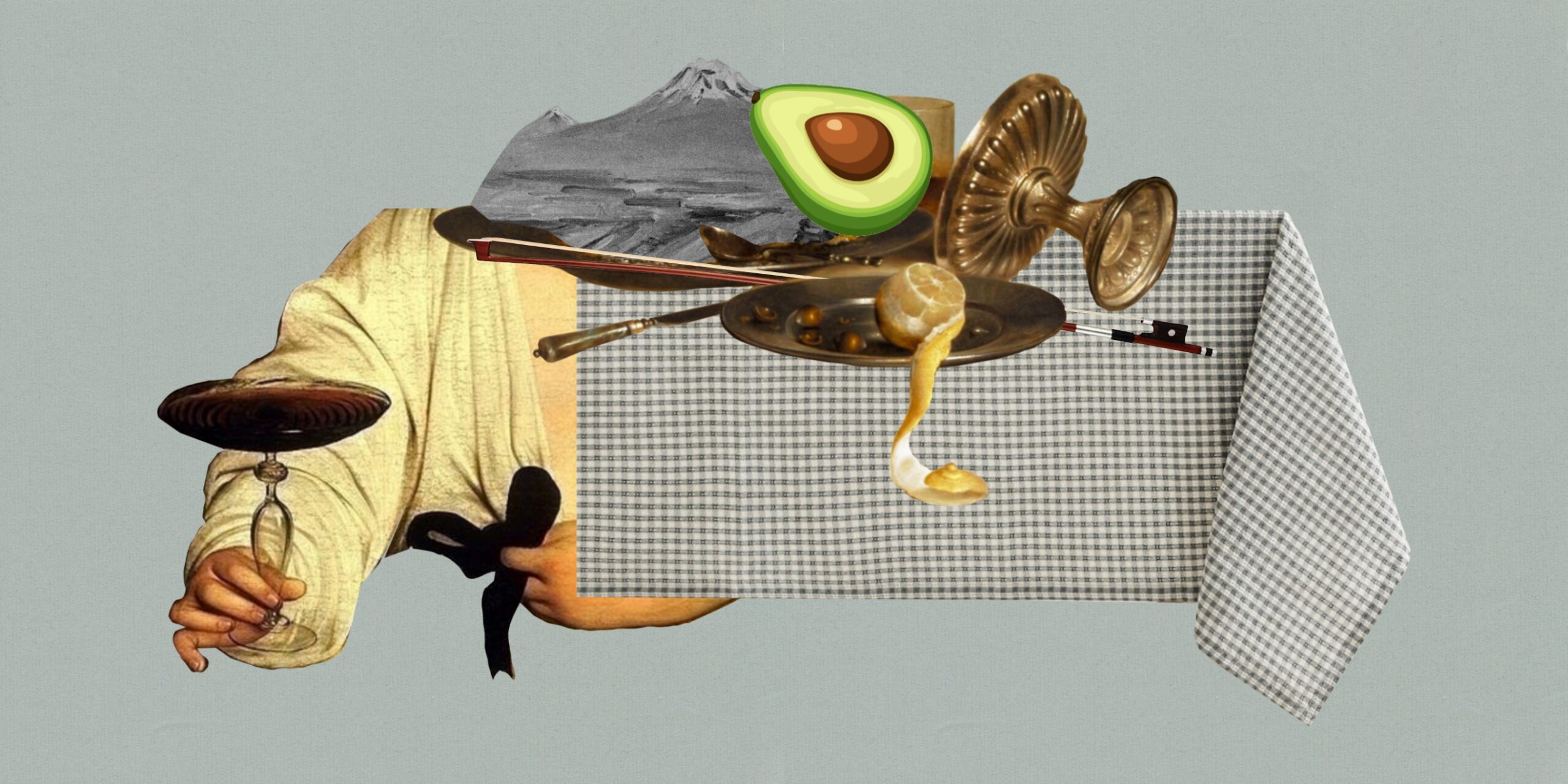

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

War leaves countless untold stories and unhealed wounds, which ultimately find their expression in art—in literature, the fine arts and cinema—to free the mind and the soul from the heavy burden of endlessly carrying those memories. Many directors took their cameras to Artsakh to document and retell the horrors that took place in Stepanakert or on the battlefield during the 44-day war that broke out in 2020. Many of them continue to work on their films, promising to share their stories in the near future. Full-length feature films are also in the work, though their production requires more time and financial investment.

One of the first films dedicated to the Artsakh conflict is “It Is Spring” [Garun a], which is about the 2016 Four Day April War. The film premiered at the Moscow Cinema in Yerevan on March 1, 2022, and is currently being screened across the country. The director of the film is Roman Musheghyan, who is well-known for his career in television, where he has authored hit the megahit TV series such as the “Trap” [Vorogayt], “The Wicked Ones” [Vervaratsnere] and a number of other projects.

“It Is Spring” is the story of three generations of men from the same family. The head of the household, Aram, is a former soldier who took part in the First Nagorno-Karabakh War and is unconditionally devoted to the Motherland; serving the Republic of Armenia is his core ideology. Throughout the film, Aram is working on his monograph entitled “The Duty of the Soul” [Hogu Partke]. His son, Gnel, is a well-off entrepreneur, who picks family over Motherland, and is prepared to do anything to exempt his son from future military service. The youngest is Levon – a young ‘Paganini’, who must choose between pursuing his father’s plans for him to study at the Royal Academy of Music in London, or his grandfather’s strict ideas about military duty.

Naturally, the grandfather’s patriotic romanticism seems much more inspiring to the young musician. All three men have loving women by their side; women who portray a specific stereotype: they are predictably superficial, always look perfect, prepare meals for their men in high heels, and are always ready to sacrifice their future and life for the sake of the men they love. Only occasionally, they might reprimand their spouses for speaking with a brash tone. The relationships Aram has with the various women in his life are particularly ill-fated: he always arrives five minutes before their death to hear that they do not blame him, have forgiven him and will always love him. These words, of course, do not relieve Aram of his deep sense of guilt.

The “uselessness” of the female characters is just one of the film’s many problems. A crucial weakness of “It Is Spring” is the script, which is tediously predictable and at the same time incredibly illogical. One can predict how events will play out from the trailer alone, but sometimes it is difficult to gauge exactly what reality and environment the author had in mind while writing the script. For example, the meeting between the grandfather and Levon’s bride-to-be takes place, incredulously, in one of the noisiest nightclubs in Yerevan, the lovers never kiss, and so on.

All the Armenians depicted in the film are idealized, positive characters; they speak formal Armenian that lacks even the most common colloquialisms even when they are yelling at each other. In the military barracks, the soldiers also speak formal Armenian, and listen to Levon’s violin solos in their free time. Later on, when the Azerbaijanis attack, they find a violin in the trench and somehow “immediately realize” that it belongs to Levon. At the same time, upon hearing that a war has broken out on the border, Aram forgets his ideals of fighting and dying for the homeland, and hurries to Artsakh “to bring Levon back”. These narrative pitfalls accentuate the dismal acting: the exaggerated facial expressions, the theatrical delivery and the artificial speech further remove the film from any claims to reality.

Aside from the protagonists, the film also completely idealizes its imagery. The avocado and croissants still life composition on the kitchen table is accompanied by scenes of pink sunsets, drone-shot views of the Armenian Highlands, as well as redundantly innumerable images of Mount Ararat. At times, it becomes obvious that Ararat has appeared in the dining-room window with the help of CGI intervention. The director probably wanted to showcase the splendor of the Armenian landscape through these scenes, but since they form at least a quarter of the film, the filmmakers only manage to turn Ararat into a tedious tautology. The authors also fall short in their attempt to present Armenian folklore. The scenes of the village wedding, the Kochari dance of the guests, come off as a nationalist caricature, while the camerawork appears to deliberately emphasize the grotesqueness of the situation.

One would be hard-pressed to find cinematic symbols that are triter and more banal than the ones populating this movie. Lightning always precedes flashbacks to Aram’s past, while rain expresses the sorrow and the relentless pain of his soul. The rule also extends to the film’s soundtrack: pathos-filled music for military ceremonies, and Komitas’ “It Is Spring” for all other occasions.

The impression is that “It Is Spring” was shot exclusively for an Armenian audience, because only locals would be able to understand what is the nature and who the initiators are behind the military attack depicted in the film’s third act. With the exception of a scene where a TV program is talking about the Armenian Genocide, the audience is not given the context in which the protagonists exist. And while the filmmakers claim that this was done on purpose, in order to assign the film a universal relevance, it begs the question as to why the enemy is excluded from this universalist framework, and why the end result is so biased. The foe is depicted as a pack of senseless predators who are prepared to kill their own, for the sake of slaying a single Armenian.

Perhaps the technical and artistic issues that riddle this production point to a bigger crisis than the one, which the Armenian film industry has been experiencing in recent decades. What we see in “It Is Spring”, is the crystalized reflection of the impossible image of national ideology and identity that our society has lived with and upheld for the past 30 years. The idealized protagonists, who live and die for virtuous principles, are prepared to forgive, save and even raise the enemy’s children. They appear on the screen to satisfy our national self-esteem, which is entirely devoid of self-criticism.

There is only one scene where Aram attempts to talk about the problems in the Armenian army, but concludes with the phrase “We are a good nation, but a bad society.” Instead, the army’s failures could have been discussed earlier in the film, making Gnel’s reluctance about his son’s military service more dramaturgically legible. Has the fear of the enemy been the sole concern of parents who have ‘freed’ their sons from the army throughout these years? Certainly not. However, the director prefers to talk only about the anonymous adversary and posits his protagonists against this embodiment of absolute evil, thus fueling our beloved national myth. But such blind idealization can have devastating consequences for any society. It hinders development, obscures reality, and leaves mistakes to be repeated. It rejects the need for growth.

We must use similar reasoning for questioning the current condition of Armenian cinema and the tendency to ignore one’s own distortions and shortcomings. Why is it so difficult for the Armenian screen to relay Armenian stories that are artistically convincing and ideologically authentic, especially in times when this an absolute necessity, such as in the post-war context? To say that this is due only to a lack of education and funding is saying nothing. Perhaps we must admit that our society has not yet developed a new epistemological approach to filmmaking, and subconsciously continues to implement the formula inherited from the USSR, according to which cinema primarily served to reproduce collective ideologies and mythologize reality, instead of revealing it. It is high time for the Armenian audiences and creators to accept that cinema is – first and foremost – a tool of critical discovery and interpretation of the world, and not a bandage to cover up our collective complexes and fears. Perhaps, only then, spring will truly come to our screens, too.

Et Cetera

Power Is (the) Truth

During March 2022, the Word—not only allegorically, but in the most literal sense—finds itself outstretched like the Vitruvian man strung from the corners of our Armenian-Russian-Ukrainian semiotic triangle.

Read moreArchive Fever: Vanadzor’s Bucolic Past in Hamo Kharatyan’s Photographs

How a tightly rolled bundle of negatives taken by Hamo Kharatyan in the 1930s slowly began to reveal astonishing, quite unfamiliar aspects of Vanadzor's life that were already on the verge of disappearing.

Read moreLilit Teryan: The Doyen of Iran’s Modern Sculpture

Known as the mother of modern sculpture, Lilit Teryan left an indelible mark on Iran’s art scene. Although teaching sculpture was banned following the 1979 revolution, Teryan continued creating and eventually returned to instruct a new generation of Iranian artists.

Read moreGyumri: A Century of Textile

In its quest to rediscover itself, Gyumri is continuing the traditions of the textile industry which in turn is inspiring new initiatives.

Read more