Central Yerevan is everything, all at once, and catering to a diverse array of aspirations. Yet, one thing is rarely found here—a hideaway from the piercing, policing gazes that enforce a certain “decency” and leaves little room to be one’s silly self. For a long while, sitting straight-backed in the lavish bars of Saryan and Tumanyan streets, I craved anonymity, wanting to neither observe nor be observed. Thus, I began a quest for “underground,” “punk” places that could offer the much-needed refuge from constant scrutiny.

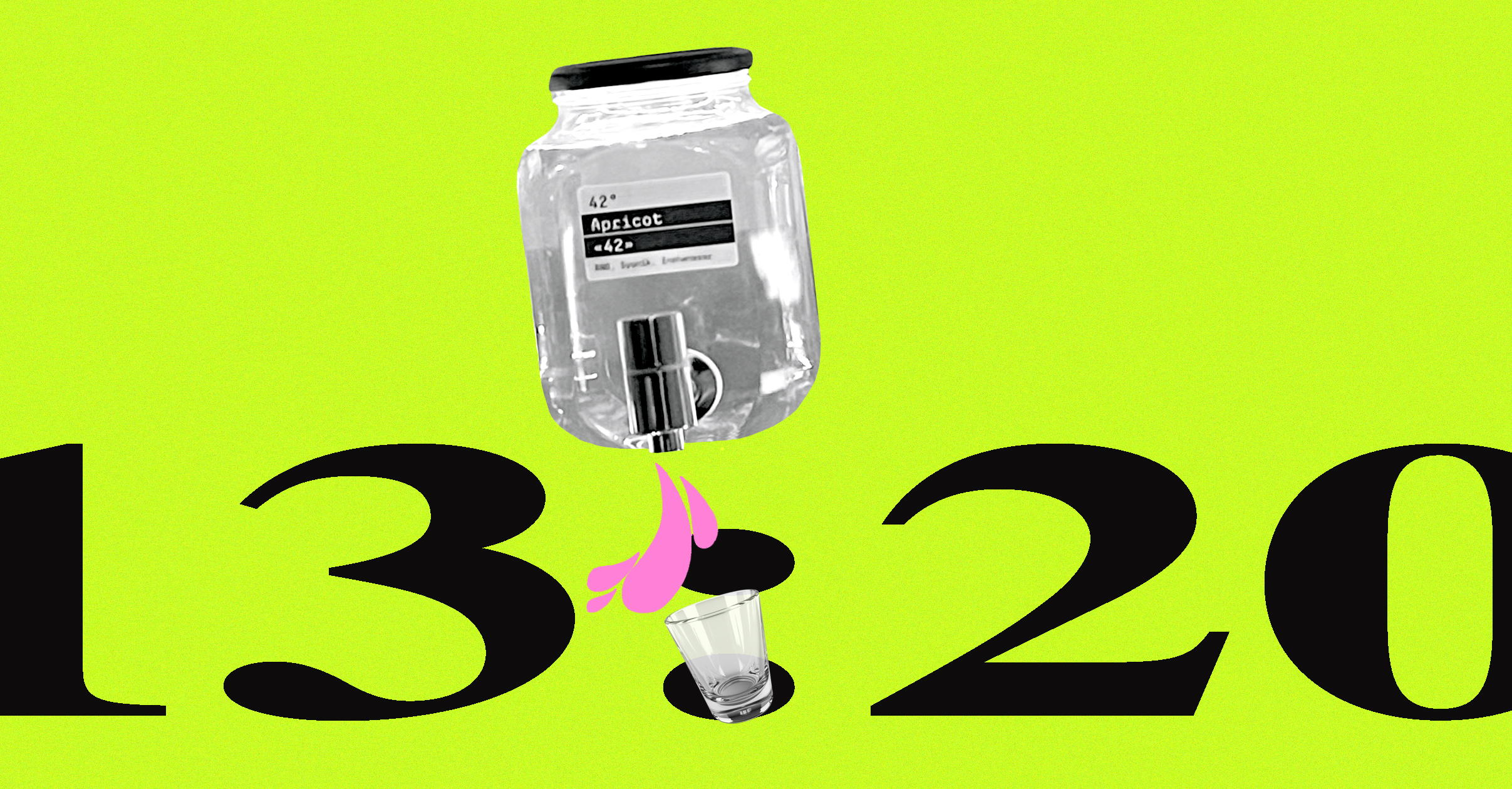

Along Buzand Street’s corridor of gentrification, tucked within what seems to be condemned rubble, lies a unique drinking establishment. Most pedestrians pass by without noticing it, just an archway leading to a decaying courtyard. Above the arch hangs an electric clock perpetually frozen at 13:20. This is not a malfunctioning timepiece but rather the bar’s name, an inside joke of the owners. Like Schrödinger’s cat, 13:20 exists in a superposition, a paradoxical state of being simultaneously visible and invisible. With its unadorned entrance and deliberately unpolished aesthetic, the bar remains a secret hiding in plain sight despite its central location.

Museum of Distillates

“When I moved to Armenia, I discovered the country’s incredible diversity of distillates,” begins Vitalique, a professional designer and one of the owners of 13:20, as we settle into a dimly-lit room behind the bar counter. “Neighboring Georgia has chacha as its national brand, but here [in Armenia], distillates do not receive the celebration that they deserve.”

The bar began with a love for distillates and a design concept, a simple wall of tapped jars that became 13:20’s centerpiece:

“My goal was to collect a distillate from every region of Armenia. This is the best part of my job, traveling around Armenia, meeting producers, listening to their stories, and tasting their spirits. Some producers I find through my social networks, while others reach out themselves.”

But there are also ad hoc situations that make the collection deeply personal. For instance, Vitalique shares a story about his family trip to Tatev:

“We went to Tatev as tourists and found a house on Airbnb. The landlady lived there and cooked for us. When we hinted that she must have some homemade spirits, she brought out an exceptional selection of 65% distillates. We immediately struck a deal and now order from her regularly.”

Vitalique’s procurement methods resemble ethnographic fieldwork, so dear to my heart: traveling to remote villages and towns, building relationships with people, and documenting regional variations. 13:20’s wall is a botanical encyclopedia of Armenia, displaying distillates from countless fruits, berries, herbs and nuts. The collection ranges from traditional varieties like apricot, mulberry, plum, pear and cornelian cherry, to unexpected options like cucumber and macadamia nut. Over 100 types line the shelves neatly.

Each liquid tells a story of regional specialization and family tradition, with distillation techniques passed down through generations by demonstration and practice rather than documentation. This intangible cultural heritage lives on in both production and consumption rituals, typically confined to the private sphere. By highlighting the significance of distillates in everyday culture, 13:20 performs a kind of grassroots cultural conservation work—a role typically associated with formal institutions. Family practices that might be taken for granted, such as a grandmother’s recipes for oghi or techniques for herb infusion, are recontextualized as valuable cultural assets and brought into public view.

Much like ethnographic museums that document and display the material culture of communities, 13:20 creates a space where the private rituals of spirit-making—traditionally confined to family homes, village distilleries, and intimate gatherings—become accessible to broader audiences. Yet unlike traditional museums where artifacts are removed from their original context, 13:20 maintains the living connection between product and practice; the spirits are experienced through consumption, creating a more immediate and sensory engagement.

Appeal of Oblivion

13:20’s charm lies in its deliberate embrace of decay and bricolage, or DIY aesthetic. Rather than gutting the space, the owner has carefully preserved the building’s rich history, peeling back layers of wallpaper to reveal a palimpsest of previous lives. These exposed sections are framed like artwork, creating a visual timeline that mirrors archaeological practice. Cracks in walls and masonry are spotlighted, allowing the buildings’ texture to be seen and felt.

The furnishings follow an aesthetic that would make any upcycling enthusiast proud. A meat grinder has been reimagined as a chandelier, while construction mesh and industrial clamps serve as decorative elements. Outdoor tables are made of cable reels and benches of hastily hammered planks.

“Everything is intentionally minimal and raw,” Vitalique notes. “It was impossible to convey my vision to the workers. Every wall is crooked here, each stone sits at an angle requiring an individual approach. It was a completely DIY renovation process, finding new ways to rub, (un)cover, and secure structures.”

The result is an epitome of contemporary architectural buzzwords, e.g. tactical/DIY urbanism, creative reuse, placemaking, and upcycled architecture. Whatever label we choose, 13:20 reflects the adaptive potential of cityscapes, easily transformed by improvisational ingenuity of individuals who claim their right to the city.

The peculiar temporality of 13:20 adds another layer of interest. Operating within a structure perpetually awaiting demolition, it exists in what might be called a “suspended present”––neither permanent nor temporary, but rather continuously improvised. This precarity and transience has become intrinsic to the bar’s identity and appeal, spreading to all its elements. The selection of distillates at 13:20 fluctuates with its producers, while some disappear, new ones emerge. The same is true about the Eshe’s menu, where nearly every evening brings a culinary experiment or collaboration between different cooks. As a regular visitor, I feel each visit might be my last. This creates heightened attention to detail and I find myself trying to imprint the objects, smells, and tastes in my memory like a game or personal ritual. One day 13:20 will inevitably be gone, demolished by a wealthy investor to make way for a new development, but it will not be forgotten.

Epilogue

As the evening deepens and colorful glasses of distillates circulate, the boundaries between tourist and local, observer and participant, preservation and innovation momentarily dissolve, creating a free-spirited (in all senses of “spirit”) and fleeting community united by shared appreciation of intangible heritage and moments of discovery.

The paradox of 13:20’s success is how its growing popularity threatens the very anonymity that allowed it to flourish. As word spreads through hushed recommendations and enthusiastic social media reviews, the yard fills with people. Yet 13:20 maintains a delicate balance between welcoming outside interest and preserving the authentic character that makes it special in the first place. That each visit might be the last makes it more urgent to catch this precious, fleeting moment where cultural statement, preservation project, and design experiment intersect.