How often have you heard about vending machines that dispense food for stray dogs in exchange for recycled plastic? Or perhaps you’ve come across stories of Sweden, one of the global leaders in sustainability, importing waste from other countries and turning it into a profitable recycling industry. Waste management has come a long way, globally.

Surely, we can endlessly reflect how far removed Armenia is from current sustainable innovations—the country has no capacity, resources, or institutional willingness to manage waste in modern ways. Aside from a largely ineffective ban on single-use plastic bags, Armenia seems to lack essential “zero-waste” policies. While recycling bins for plastic, paper and glass have been introduced in Yerevan and a handful of other cities, these efforts remain insufficient. Most environmental initiatives and waste management services are driven by NGOs rather than the government.

Despite these challenges, Armenians have retained a number of green habits, rooted in practical traditions from the Soviet era, without necessarily labeling them as sustainable. It’s fair to say that nearly every household repurposed plastic bags as trash liners—a practice that many Westerners might find both surprising and remarkably resourceful.

I grew up in Artashat, the administrative center of the Ararat region, which many agree offers the best view of Mount Ararat. When I was around ten, I remember a beige Soviet car cruising down the streets of our town as our neighbors handed over glass bottles.

Seeing that others were getting something in return, I decided to start collecting bottles myself, despite my parents’ warnings not to get my hopes up. Finally, the day came, and I proudly handed the bottle collector two boxes filled with Jermuk bottles, along with some from local lemonade and beer. I had been hoping for some cash, but instead, I walked away with a few rolls of cheap toilet paper and dishwashing soap.

Years have passed since my very first recycling experience. I moved to Yerevan, but that beige Soviet car—be it a Vaz-2106 or Gaz-24—kept coming by to collect glass bottles.

Recently, while visiting Artashat, I noticed those cars were nowhere to be seen. However, my father recalled where most of the collected bottles ended up. On a Sunday afternoon, we drove to the Shahumyan settlement just outside the city. There, a medium-sized building resembling a factory stood surrounded by large bags filled with glass bottles. The security guard informed us that no one worked on Sundays, but, as luck would have it, the owner appeared at that very moment.

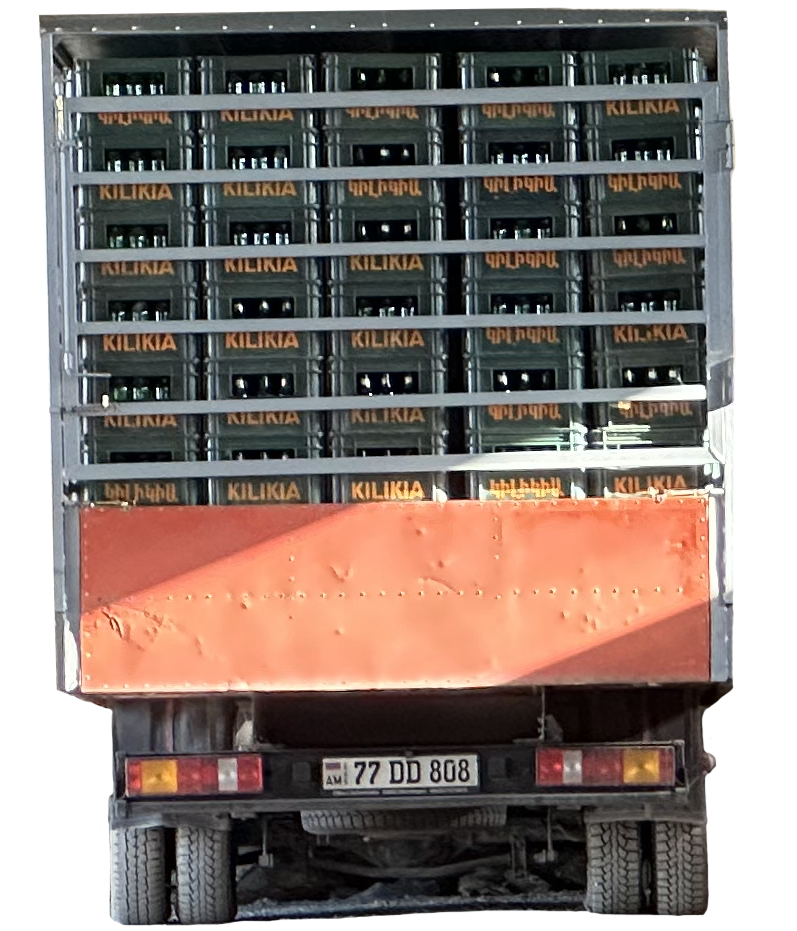

Andranik Simonyan, 67, turned out to be an old acquaintance of my father’s, known for his lemonade production. To make his 25-year business more sustainable and independent, Andranik took control of the glass bottle collection process himself in 2013.

“I’ve been doing this for 11 years, becoming the first to open a glass collection facility in the Ararat region,” Simonyan told us. “Those cars you see on your street? They earn more profit than I do. But my real gain is that I supply my factory with cheaper bottles, instead of buying new ones.”

A single bottle can be worth anywhere from 10 to 35 AMD, or even up to 100 AMD for a high-quality brandy bottle. Shattered or cracked glass is accepted by weight and sold to glass-making factories.

“There are 11,000 beer bottles here, most of them are already clean. I’ll take them back to the factory tomorrow,” Simonyan said, guiding me into a large hangar where neatly stacked glass bottles filled plastic crates, and aluminum caps lay scattered across the floor.

Whether he will eventually take on the challenge of recycling the aluminum caps or decide it’s too costly for his business is still uncertain. But what he’s already doing requires a tremendous amount of effort, which is why he employs a team to sort through hundreds of thousands of bottles.

Simonyan’s initiative wouldn’t succeed if residents like my neighbors didn’t collect bottles in their backyards. Take, for example, 57-year-old Naira Safaryan, who strings her clothespins on an old shoelace for easy access while hanging her laundry (nice lifehack!). “We haven’t seen the car for a while,” Naira says when I ask if they still hand over bottles. “Recently, we’ve been paying close attention to the car horns. We’ve already collected a lot of bottles.”

Naira’s family doesn’t do it for the money, as there isn’t much to be made. “We know there’s a car that collects the bottles, so we don’t throw them away—glass is a valuable material,” she explains.

I’m not sure about the color, but other cars also collect plumbing fixtures and various metals. For example, when my father replaces our taps, he discards the broken parts but keeps the functional ones to sell to these collectors rather than just tossing them.

Such practices predate even my 64-year-old father, Gegham. He recalls a time when all products came in glass containers, and returning an empty bottle or jar was necessary to purchase more Jermuk, matsun (Armenian yogurt), milk, or other goods. Reusing the same glass container two or three times was more efficient than producing new ones.

At the Soviet markets, everything came packed in large sewn bags, which were often reused at home. Bags made from hemp twine were sturdy and could be repurposed as door mats.

Over time, plastic gradually began to replace glass and other reusable materials.

“There was a locally produced laundry detergent in paste form called zhemchoug (the Russian word for pearl). It was the very first product I saw packaged entirely in plastic,” my father recalls. “My first reaction was, ‘Oh, we’re getting the plastic container with it!’”

This mindset hasn’t changed over the years. When we buy candies in plastic containers, my mom often repurposes them to store dry fruits.

Growing up in this environment, I naturally embraced an ideology the world now calls green, eco-friendly, etc. I was taught to care, keep my surroundings clean, and avoid overbuying, even without modern innovations, laws, or trends.

But still, I might find myself spending hours in a supermarket, choosing the perfect product—each one nearly identical, sometimes with only slight variations in color or shape—creating an illusion of infinite choices.

But one thing remains unchanged: resources are limited. In a world where more and more people seek convenience over sustainability, it’s the seemingly mundane practices by ordinary people like Andranik, my neighbors, and my parents that remind us of what we could be doing better.

Issue N2

Design & Recycling