Trying to make sense of religious and spiritual life in Armenia is a difficult task. While nearly the entire population identifies as Christian, and most are followers of the Armenian Apostolic Church, what that looks like in practice can range from regular attendance at Sunday mass to posting images of cute lambs for Palm Sunday.

Religious holidays remain widely observed across the country, though for many these traditions are less about faith and more about cultural identity. Take Lent or Mets Pahq. Once a deeply spiritual observance preceding Easter, it had been largely forgotten, especially among secular Armenians.

This, however, appears to be changing. A growing number of Armenians have embraced Lent, although most view it as an opportunity to practice personal discipline or follow a diet rather than a religious observance in commemoration of Christ’s fasting in the wilderness. From upscale bistros to corner bakeries, Lenten-friendly offerings are suddenly in vogue—and not just for the pious.

Nerses Gaghazaryan, a clergyman at St. Gregory the Illuminator Church in Yerevan says what started as a diet trend about a decade ago has evolved. Today, the popularity of Lenten foods suggests that the practice is finding its way back into Armenian daily life, albeit in new forms.

Beans, Feathers and an Onion Named Aklatiz

Before smartphones and Google calendars, keeping track of the days of Great Lent wasn’t always straightforward. One old story captures just how easy it was to lose count.

According to the tale, on the first day of Great Lent, a village priest placed 49 beans in his pocket—one for each day of the fast—discarding one daily to mark the passage of time. A practical, if rustic, solution. But one day, while doing laundry, his wife noticed the pocket full of beans.

Assuming her husband just loves beans, she tops up the supply. Unaware of the mix-up, the priest continued discarding beans faithfully and endlessly. And so, while the rest of the country broke their fast and celebrated Easter, this one village lingered in Lent, trapped in an eternal bean-count.

To avoid such mishaps, families turned to a rather endearing enforcer: Aklatiz, also known as Pas Pap—a Lenten doll made of dough, onion, or potato, sporting seven feathers, each marking a week of the fast.

Secretly crafted by the eldest woman in the house, Aklatiz wasn’t just a calendar—he was the terrifying timekeeper of the household. Every week, a feather was plucked. Anyone caught sneaking a bite of cheese or nibbling on meat might get scolded and threatened to have a spoonful of pepper placed in their mouth or a pretend pelting of stones. Children feared him; adults respected him.

And yet, when the ordeal was over, it was payback time. The kids would parade Aklatiz out to the fields, beat him with sticks, and toss him into the nearest stream like a soggy effigy of dietary discipline. Some claimed his onion head would sprout and bring blessings—others used his feathers to sweep flour off the table or tuck them under mattresses for good luck.

Because Aklatiz, despite his stern demeanor, was also a bearer of fortune.

Today, Aklatiz no longer keeps watch in most Armenian households. Though Easter remains widely celebrated, the ritual of Lent has faded from many homes. Still, in some households, the onion doll’s role as a Lenten enforcer lingers on as a cherished Easter tradition.

Nut Milk Before It Was Cool

As it turns out, Armenians were pioneers in using nut and seed milk long before it became trendy. During Lent, when dairy products were off-limits, they turned to plants for a creamy alternative. It was called anshoort, and it wasn’t a trend—it was a necessity.

Nuts and seeds were pressed not only for oil but also for their milky liquid. Seeds from sunflowers, watermelons, and other melons, along with nuts, were pounded and mixed with water to create a juice known as kat (milk). This liquid was strained and used as a dairy substitute, particularly for flavoring soups and stews.

One popular Armenian Lenten dish was arganak, an herb-based soup flavored with anshoort. Though once a common pantry staple, anshoort has since disappeared from modern Armenian kitchens and is rarely, if ever, mentioned in cookbooks today.[1]

Still, recreating it at home is simple: grind almonds or seeds as finely as possible in a food processor, add water, and blend thoroughly. Bring the mixture to a boil, then strain it through cheesecloth or a fine sieve into a jug. The result is a dairy-free liquid that once sustained Armenians through the long weeks of Lent.

Mijink: A Mid-Fast Pause With a Sweet Surprise

Unlike many other Lenten traditions, Mijink is still celebrated in many Armenian households, likely because it’s an excuse to indulge in a delicious treat. Marking the midpoint of Great Lent, Mijink offered a culinary and symbolic pause in the otherwise strict fasting period.

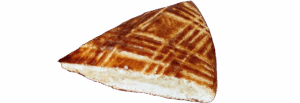

On Mijink a special ceremony was held to bless butter, which was then mixed into the household’s regular supply for cooking throughout the year. The highlight was a special bread called bagharj, made with the blessed butter and often referred to simply as Mijink. A symbolic item, like a coin, bead, or bean, is hidden inside the bread. Whoever finds it is said to have good fortune for the year ahead.

Mijink doesn’t carry formal religious significance, it is more of a cultural tradition and continues to be a festive, beloved tradition in many Armenian homes.

***

Great Lent is also known as “Bread-and-Salt” (Aghuhats)—a reference to the practice of the most devout believers who would consume little more than bread and salt during the fasting period. In some regions, the end of Lent was also marked with the ceremonial sharing of bread and salt.

In Armenian culture, bread and salt carry deep symbolic meaning. They are more than basic sustenance—they represent hospitality, humility, and respect, especially toward guests.

While the religious devotion during Lent in Armenia isn’t as widespread as it once was, the persistence of customs through plant-based dishes, symbolic rituals like Aklatiz and Mijink, and the quiet return of fasting practices reveals how deeply rooted these traditions remain in Armenian culture. While these traditions are no longer universally practiced in their original form, they continue to shape collective memory, identity and contemporary life.

Footnote: