Let me disappoint you by starting with the dictionary definition of disappointment:

Disappoint (v.) from dis- “reverse, opposite of” + appoint, “undo the appointment, remove from office,” “to frustrate the expectations or desires of,” “defeat the realization or fulfillment of,” “fail to keep an appointment.”

Յուսախաբութիւն/Husakhaputyun (Western Armenian) from յոյս (hope) + խաբէութիւն (deceit), “cheated out of hope.”

Հիասթափություն/Hiastaputyun (Eastern Armenian) from հիացմունք (admiration) + սթափվել (sober up, come to your senses), “To sober up from admiration.”

However you look at what the understanding stands for, the obvious thing is that the realities, standards, hopes and wishes of the “disappointed” and the “disappointer” have probably diverged some time before the “disappointment,” if they had ever intersected at all.

So why does this word torment human interaction and why is it so acute in Armenian culture and its political lexicon?

For the word to emotionally distress the “disappointer,” it would have to be assumed that the view of the “disappointed” is validated.

In Armenia (i.e. the spoken Eastern Armenian culture), we use the word ապրես (apres) often. Apres means “may you live” and it is used as bravo, the opposite of disappointment. Used when no one’s hopes have been crushed, no one’s admiration sobered and no expectations reversed and when someone has excelled in NOT disappointing. Years ago, when my grandfather said apres to me for bringing him a glass of water (quickly and without spilling it), had I been a puppy, I would have wagged my tail. Now, when a 16-year-old says apres to me for lending them a pen they did not think to have with them in the first place, I want to growl. It is an innate objection to being “thanked” through (a language that insinuates) evaluation rather than gratitude. I take words seriously; I’m a reporter.

My fixation with this particular word started back in February 2018, when EVN Report was working on a series about the 1988 Karabakh Movement, a few weeks before the Velvet Revolution would break out. That year marked the 30th anniversary of the beginning of the Movement, and we were talking to the participants and witnesses of the events that would lay the foundations for the country we have now. They all said they were disappointed. When asked why they had not done anything about it, the answer was, again, because they were disappointed. I dare presume here that it was a classic case of հիասթափություն (hiastaputyun), people had “sobered up” from “admiration” and remained sober for 30 years.

About two weeks ago, amidst a pandemic, Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan spoke of the “disappointed” in a Facebook Live session. He listed them and the reasons for their disappointment, categorized them into groups: relevant and non-relevant. They included representatives of the former regime, who according to Pashinyan, are still holding their breath, waiting for the post-revolution party to end; people who served the former regime but were never promoted to higher ranks; adherents of the criminal subculture that is no longer needed to help rig elections or silence critics; former participants of corruption, who are now deprived of their additional incomes and their impunity; political forces who collaborated with the former regime and are currently left without prospects; opposition forces whose message has now become obsolete; Western-leaning forces; forces leaning toward Russia; the oligarchy deprived of its privileges; media outlets that lost state sponsorship; clergy members whose divergence from a spiritual life is now exposed in the face of a government with values; some diasporan structures who are no longer the intermediaries between the government of Armenia and the diaspora; people who expected opportunities and positions because they had joined the revolution; friends and relatives who expected their lives to change because their acquaintance is now Prime Minister.

Pashinyan titled his live «Մեծ հիասթափության» մոդելավորումը, roughly translated to “Mapping of the ‘Great Disappointment.’” What triggered my musings on disappointment were the quotation marks in the Prime Minister’s title. Was disappointment, which psychology defines as a “subjective and individualistic emotion,” and which, in our context, is often confused with an opinion, being rebuked or called out by Pashinyan?

Pashinyan had listed the disappointed ones in the classical English meaning of the word, those whose “appointments have been reversed.” But the group that subscribes to the use of the word with nuances more specific to Armenian—with root words like “hope,” “admiration,” “deceit,” “sobering up”—were not mentioned.

Here are some of the comments left under the Prime Minister’s live by those left out of the list:

- [10:30]: “Mr. Pashinyan, I too am extremely disappointed and I’m not talking about corruption, I’m talking about this quarantine.”

- [14:52]: “There will be no disappointment if there is a tough and smart government.”

- [32:52]: “The greatest source of disappointment is the fact that Serzh is still at large.”

- [29:31]: “Mr. Prime Minister, there is disappointment because pensions and salaries are not being raised.”

There were 7,400 comments left during a 32 minute “conversation.” While many were simply saying hello and expressing admiration, some cursing and calling Pashinyan a liar, many others had specific requests and advice, a minefield of disappointment because there will be requests unanswered and advice not taken.

The Theory of Disappointment, developed in the 1980s and still used to forecast sports fan behavior, says “people contemplating risks are disappointed when the outcome of the risk is not evaluated as positively as the expected outcome.” The theory proves that disappointed individuals focus on alternative outcomes that would have been better than the one actually experienced—to the point that even positive outcomes can still result in disappointment.

Hundreds of thousands of people in Armenia took to the streets in April and May 2018, despite considerable risk. Their current reality fades in comparison to how highly they evaluate the personal risk they took two years ago. One example researchers of the theory bring up is how a lottery win of $10,000 can be a disappointment when the winner realized that an even larger prize was available. In parallel, people today may not notice that salaries and pensions have increased because that increase has not effectively improved lives.

It’s a catch-22. Disappointment is the subjective emotional response of an individual to the failure of expectations or hopes to manifest in full glory; expectations so personal and hopes so idealistic that they cannot be used as objective measures to evaluate a country’s reality. Disappointment is a major factor in politics. Depending on how many times the word is uttered in one context or another, when the next election rolls around, voters may choose someone new to be disappointed in.

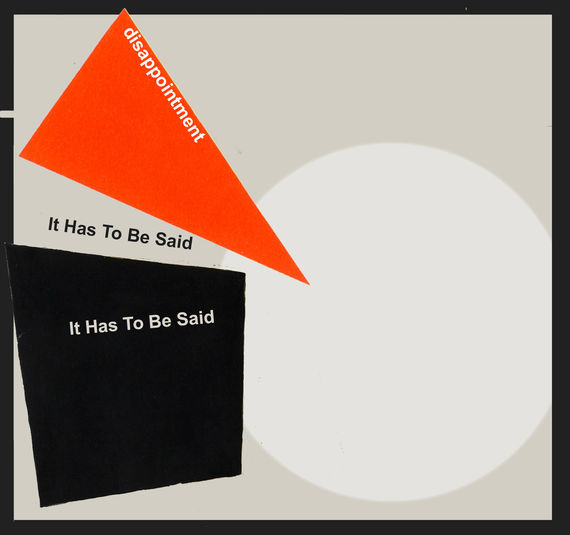

It Has To Be Said: The Swallow’s Fortress

As Armenian Genocide commemorations were cancelled around the world, descendants of the survivors found alternative ways of remembering, honoring and demanding.

Read more