It was the morning of July 23 at around 9 a.m. I got a call from a colleague. “They have finally agreed to let the media in,” she said. “Are you coming?”

Yes.

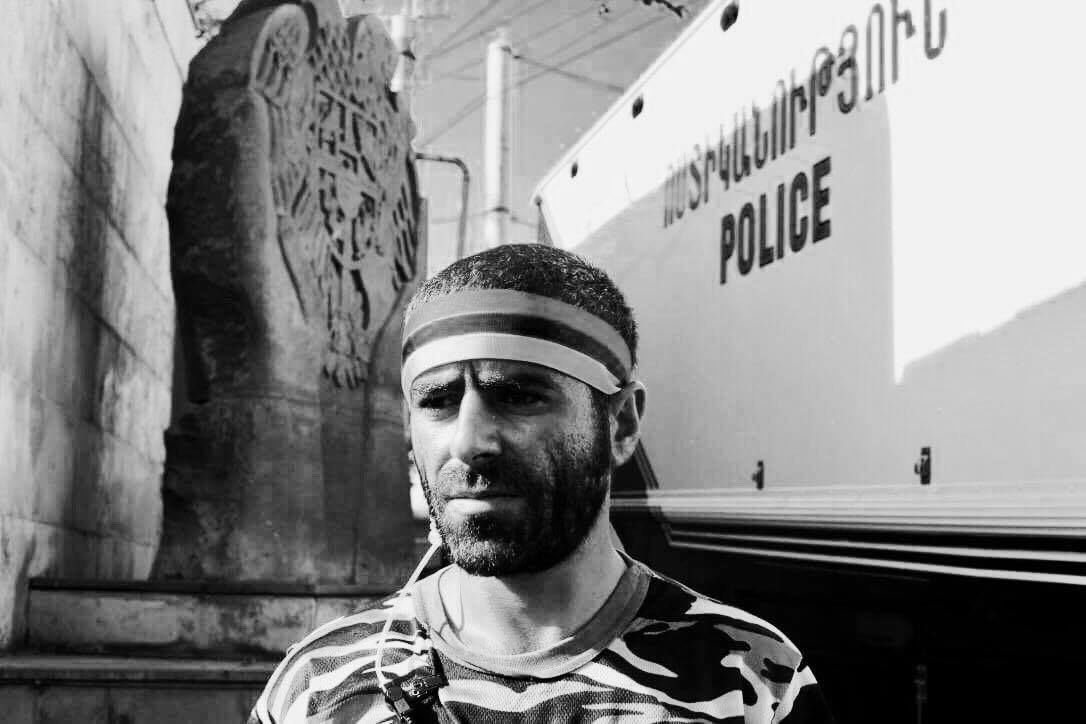

The Daredevils of Sassoun, a group of armed men had taken over a police station in the Erebuni district of Yerevan in the early hours of July 17, 2016. And similar to what happened in Karabakh that April, when the national narrative was never calibrated (war, escalation, or worst ever breach of the ceasefire agreement?) we had woken up to a situation with no commonly agreed upon description (terrorism, armed rebellion, or self sacrifice?). In light of the external miscalibration, an internal one arose and the veterans of one became the frontrunners of the other.

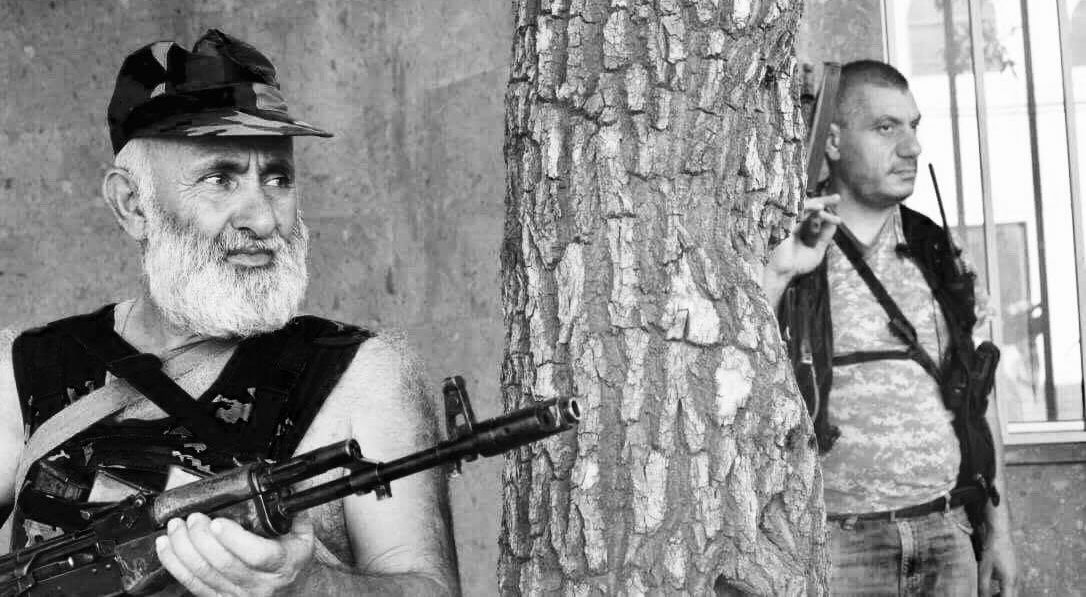

A group of journalists were allowed into the vicinity of the Erebuni Police Station under siege. Were we afraid? I was not, and others did not seem to be either. We ought to have been. There were journalists who called the Daredevils of Sassoun “terrorists,” journalists who called them “armed men,” “war veterans” — none was afraid more than the other.

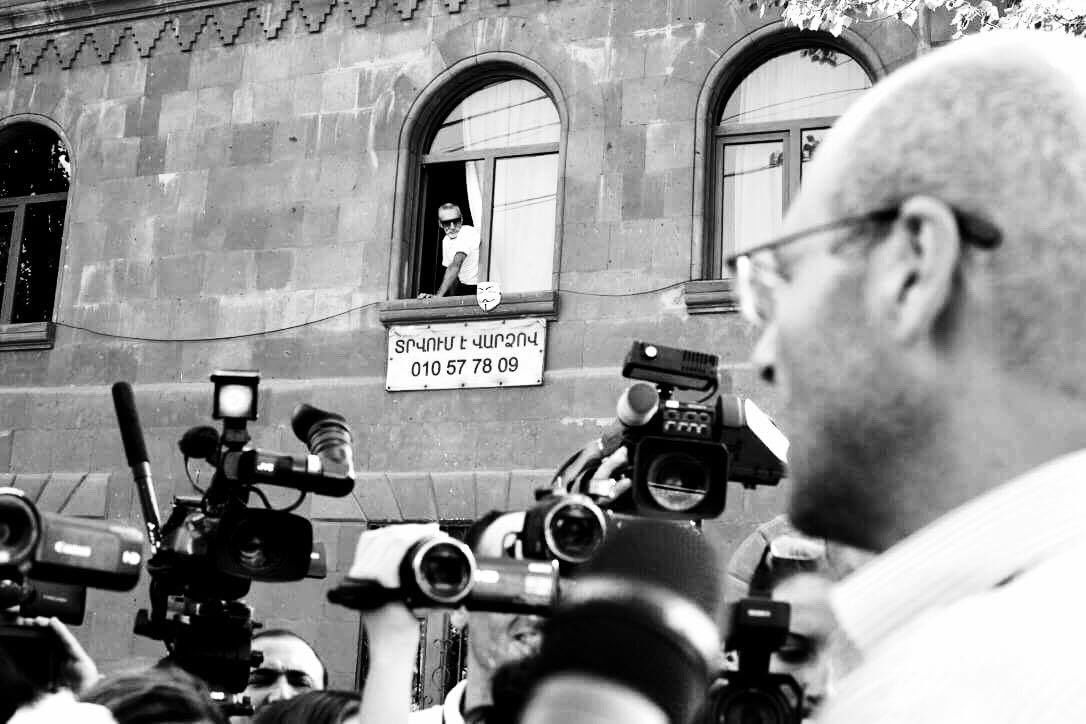

Were the men who had killed a police officer, taken six others hostage, had control of the entire Yerevan internal security arsenal, not a threat? Were the Internal Security Forces behind us, who had been crowding the city’s police stations with detainees and only days later would target journalists during clashes with protesters not a threat? This casual group of journalists readily put itself between two armed groups; one more unpredictable than the other. What is more, contrary to the initial agreement, communication was taken away from us; cellphones, Live equipment, anything that could be used to establish direct communication with the outside. Unfortunately, we were only bothered, not outraged.

A year has passed since and things are surely not clearer.

States stuck in an overextended transition like Armenia embrace alternative facts, post-truths and half-truths that abort great expectations in order to maintain comfortable status quos.

Like that Roman general who swallowed his daily poison with a grain of salt to cover the bitterness, apparently we too have built up that immunity and in the process misplaced our fears.

Noon. July 23. Members of the Daredevils of Sassoun approach us and say they will not be speaking to the media, but then they do because they had been waiting for the opportunity. The agreement between them and the authorities seemed to be the following: the Daredevils would let all the hostages go, would not appear in front of the media armed, would meet with the media at a designated spot and not allow anyone close to the main building they were occupying. For their part, the authorities would allow an unlimited number of media representatives in and set up a media center with WIFI. The hostages were released, we went in but the media center was not there, the Daredevils were fully armed, and before the authorities agreed to finally set up the connection, we wandered around well beyond the designated meeting point.

The situation outside the compound between supporters of the Sasna Dzrer and the police was much more intense and explosive than it was inside the compound that day. Over the course of two weeks, as the Union of Informed Citizens NGO has estimated, 700 civilians were detained without any grounds and around 100 people were hospitalized after police used excessive force and special means against the demonstrators.

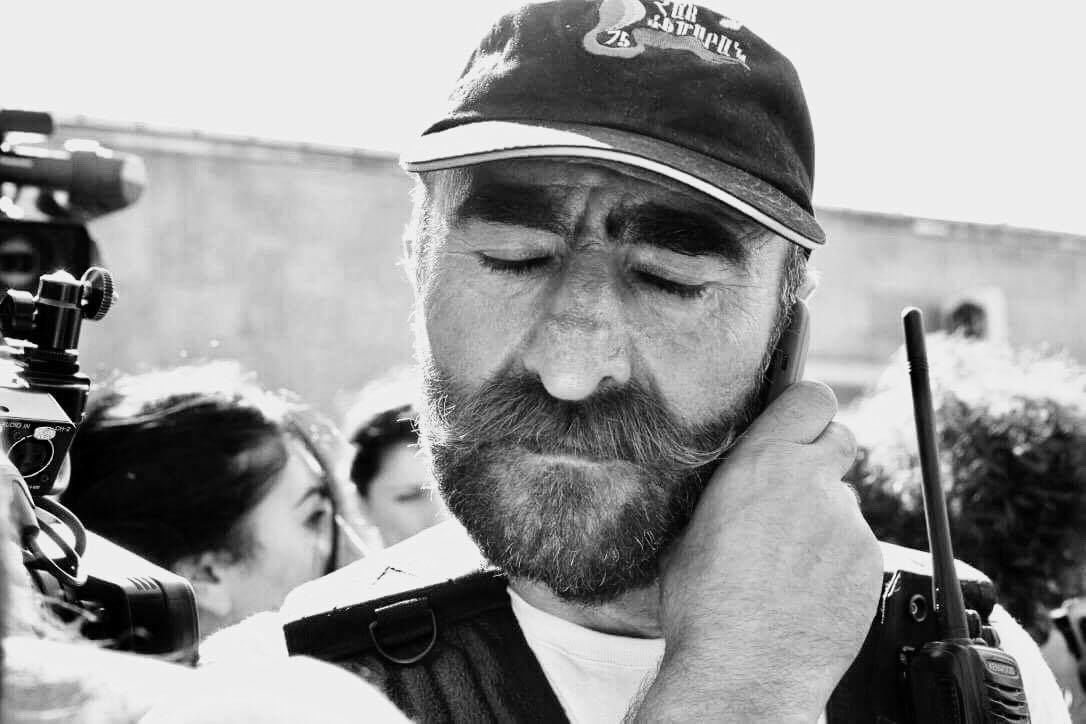

To watch Pavlik Manukyan, one of the leaders of Sasna Dzrer, and Vitaly Balasanyan, the secretary of the National Security Council of Artsakh (Nagorno Karabakh Republic), a former presidential candidate and retired Major General and at the time, one of the designated negotiators, get into a yelling match was most telling. There were no civilized negotiations, and there was no reciprocal respect or fear.

The day before was my wedding, and amid all the upheaval and the endless nights and days reporting from Khorenatsi for Civilnet, I thought, “How symbolic that we should get married in Armenia during times of change.”

A year has passed since and nothing has changed.

The same atmosphere of no reciprocal respect or apprehension is now prominent in the courtroom during the Daredevils of Sassoun trials. It seems what the Sasna Dzrer has really achieved is the right to publicly voice contempt towards incompetent authority.

Around 4 p.m. the authorities bring in the father of one of the armed men, a man in a wheelchair, the only parent of any Sasna Dzrer member to publicly condemn his son’s actions.

Of course, by then, the connection was set up and this segment we could transmit live. He accused his son of abandoning him, of letting him starve now that there is no one to care for him. He reminded his son that his responsibility was first towards his parent above anything else. The son tried to explain, “I did this for you,” but the father’s yelling was louder than his voice. And that is the Catch 22 of our reality — the causes of complaint are the same, reactions are conflicted.

Antranik Boghossian approaches the hysterical parent, smiles and holds his hand. Silence. The man hangs his head. He seems ashamed.

Two wheelchair bound men. Two men from the same reality but with opposite perspectives. Boghossian had been part of a mission to assassinate the Turkish Ambassador to Yugoslavia in 1983 as a member of the Justice Commandos of the Armenian Genocide (JCAG) and was shot in the process. He was now invited to be a part of the negotiating group along with Alec Yenikomshian, who lost an arm and his sight on a mission with the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA). Both ASALA and JCAG are considered terrorist groups by most countries. It was Armenia that gave asylum to some of the men who took to violence in order to counter injustice.