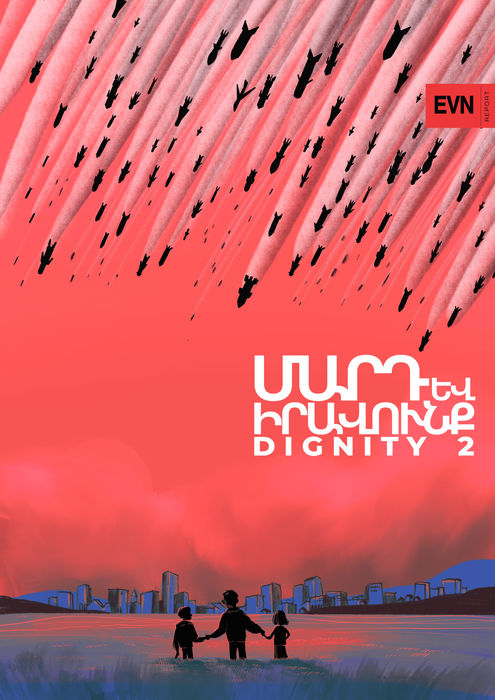

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

The fact that we are in a deep crisis is not disputed. Many point out, rightfully so, that it will only be possible to overcome the crisis through a concerted effort. But first, we need to understand where we are now. We need to be honest, admit mistakes, learn lessons and move forward. There are many “must dos,” which is natural in the circumstances of this national catastrophe.

Where Are We and Where Do We Stand?

Some analysts claim that Armenia was defeated due to weak political leadership and not because of a mismatch in military capability. They argue that the Armenian army was efficient and capable of both defense and launching a counterattack, but not ordered to do so. Such an assertion is contradicted by the report submitted during the war by the Chief of the General Staff of the Armenian Armed Forces, stating that the Armenian side would not be able to resist the Turkish-Azerbaijani alliance and that the war must be stopped. Even though we successfully resisted the enemy on some fronts and recorded some successes, that in itself does not mean that our army has not been defeated.

The current and previous governments both bear responsibility for this defeat. Upon coming to power (if not right at the beginning, then within the first year), the Pashinyan administration realized that it had inherited – as it itself asserted – a bad negotiating position and an army that had been plundered for years. It would be naive to claim that, right after the 2016 Four Day April War, a new war instigated by Azerbaijan was not expected in the coming five to ten years, given Azerbaijan’s intensive military expenditure and its explicit declarations that it was ready to solve the conflict by force. Knowing and comprehending all this, Nikol Pashinyan apparently tried to strengthen the army and introduce a new feature – starting the negotiation process from a new point and accentuating that any solution of the conflict must be acceptable for three populations (Azerbaijanis, Armenians in Armenia and Artsakh) – into the negotiation process. But he made a number of mistakes in this context. For example, he tried to bring Artsakh back to the negotiating table, but at the same time announced, during the 2019 Pan-Armenian Games, that “Artsakh was Armenia, period.” Of course, that statement was primarily intended for an internal audience, and the nuances between the concept of the “Armenian world” and the “Republic of Armenia” were lost in translation, but it was short-sighted in terms of anticipating the reaction from the external audience. Also, he demonstrated excessive self-confidence after the July border escalations in Tavush; whereas, in hindsight, it would have been prudent to stay modest, keep his head down, continue to strengthen the army and prepare for the upcoming war. Former President Robert Kocharyan insisted in an interview that the border incident was provoked by Armenia despite the report by the Chief of the General Staff of the Armenian Armed Forces that, “War must be avoided at all costs, because our opponent is no longer only Azerbaijan, but also Turkey.” In another interview, Prime Minister Pashinyan did not deny that Armenia had taken the path of aggravating the situation.

Former Secretary of the Artsakh Security Council Samvel Babayan, in turn, insists that he warned the Armenian military-political leadership about the impending war back in 2018, and that there was a short period in which to prepare for a new war. Nevertheless, no attempt was made to understand the problem in depth, he said, adding that the war could have been prevented by building a powerful army and acquiring new weapons and ammunition that had not been done adequately in the previous 10-15 years.

During the actual war, many questions emerged regarding the steps being taken by the state, raising legitimate doubts. For example, despite an announced mobilization, in practice, those sent to the front were predominantly volunteers. Minister of Defense Davit Tonoyan, who has since resigned, spoke of the lack of military equipment, confirmed also by Samvel Babayan, which could explain why a full deployment was never conducted. However, in his interview, Babayan criticized both the Armenian and Artsakh authorities for not providing the necessary level of mobilized resources. Both the current and former regimes share responsibility for the lack of military equipment, and they must honestly admit this. There was also criticism of the decision not to attach volunteers to the army.

In his interview, Babayan disclosed these and other issues (conspiracy, betrayal, desertion, failure of specific military operations, etc.), all of which deserve thorough investigation. Babayan also made contradictory statements about the assistance provided by Armenia to Artsakh; at the beginning of the interview, he claimed that Armenia had provided 6,000 to 7,000 mobilized forces, instead of the more than 11,000 it allegedly was supposed to deploy. However, minutes later, when asked by the interviewer whether Armenia was not sending troops to defend Stepanakert, as the Artsakh President had stated in a notable recording, Babayan said that Armenia had used absolutely all its resources in the war, but also hinted that Armenia seemed to have deliberately delayed sending the Buk surface-to-air missile system to Artsakh. The Armenian people should not be satisfied with allegations/speculations and contradictory statements; there should be explanations and clarifications at the highest level in the form of a special commission that will elucidate the events, whether by this government or the next. Otherwise, we will have another unexposed “March 1” or “October 27.” (Both the 1997 October terrorist attack in which the country’s Prime Minister, the Speaker of the Parliament and several other parliamentarians were assassinated, and the 2008 post-election clashes and killing of 10 people have never been fully exposed.)

The demands for the resignation of Nikol Pashinyan and his government and the holding of early parliamentary elections have an objective basis, but who is demanding it, and how, is another matter. Armenia’s PM stated that he is ready to hold a pre-term parliamentary election in 2021, whereas his main opponents do not want the current authorities to organize the elections; they demand the resignation of the PM and the formation of a temporary government, which will organize the anticipated elections. Opposition forces want to come to power, but are not offering clear solutions for steering the country out of the crisis. Almost all the opposition forces have no legitimacy; they have squandered the trust they had. There is the perception among some political forces and individuals that the public is indifferent and passive. It is no coincidence that many citizens think that only the soldiers have the right to demand the resignation of the Prime Minister, as there is great trust toward those who put their lives on the line during the war.

There is no standard solution to the crisis Armenia is currently experiencing. New political forces may also be formed, consisting of people who have heretofore never been involved in politics, or have been engaged but remained untainted. People are desperately searching for the necessary skills and pragmatic approaches to get the country out of this situation.

Underlying Issues

The biggest tragedy and misfortune of our nation is that, in the absence of statehood, Armenians for centuries lived, thrived and contributed to other societies – from Baku, to Tbilisi to Constantinople. Today, we have a state and yet there are more Armenians outside its borders than inside. Over 2 million Armenians live in Russia alone. There is no doubt that, since the independence of the Republic of Armenia in 1991, the country has faced crippling difficulties and challenges, forcing many to flee in search of a better life. Those challenges have not disappeared. The majority of those who stayed continue to face them, but we stayed. And now, once again, many are making preparations and expressing their desire to leave their homeland.

For any society, its citizens are its most valuable resource. In the face of such a small population, could we have triumphed? Yes, we could have. We could have if we had better governance, if we had developed our military industry, built a powerful army, established social justice, provided a dignified life for the population, etc. But this did not happen. Successive administrations, and society in general, all remnants of a Soviet legacy, did not understand the value of statehood.

But if most of the Armenians living abroad were here, we would have unanimously demanded more from our government, we could have fought better, we could have had a stronger, more viable state. I often wonder what future generations will think about us when they read in history books about the crushing defeat of 2020. What will they think of those of us who were here but didn’t demand enough, or fight hard enough? What will they think about those who chose to leave simply to secure a more prosperous life, instead of helping to create such conditions for all?

The concept of statehood has problems of perception. Within society, there are many instances where attitudes toward the homeland are not as they should be. Many of my compatriots love the homeland from the periphery. In addition to not living in the homeland, there is another very important truth. The homeland is defended with blood – with your own blood, not with the blood of your neighbor. Fleeing from the battlefield, leaving the calls from the military commissariats unanswered, fabricating excuses or simply running away from one’s duty to the homeland is simply unacceptable. On the other hand, it is also defended with a strong military and, as we saw during this war, with advanced technology. Soldiers, reservists and volunteers died in massive numbers by drones they were powerless against. Had we invested in the scientific community, equipped with the knowledge, resources and capabilities to create a modern, technologically advanced armed forces, had we created the conditions for people to stay instead of fleeing in search of a better life, perhaps the outcome would have been different.

Another important issue is the attitude of Armenians living in Armenia regarding Artsakh itself. Over the past few years, talking to many Armenians (including friends and relatives) on various occasions, I have ascertained that they do not really consider Artsakh their homeland. There have been many such expressions: “Artsakh is not ours,” “Who needs Artsakh, let’s give it away and be done with it,” and so on. In this context, criticism is often voiced against the state, that it has not been sufficiently transparent about the negotiations on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict for years – in particular, as to which territories are subject to compromise and which are not. Taking into account the geopolitical and legal-political realities, these criticisms may have objective grounds in relation to the seven regions adjacent to the former NKAO, but there should not have been any doubts regarding NKAO (that it is our homeland) among our compatriots.

Throughout the war, all Armenians actively donated to the All-Armenian Fund, and many compatriots in Armenia and abroad encouraged, persuaded and supported new forms of aid (through various means). Had we fought just as hard to eliminate the ills that existed in our society in peacetime – from corruption to impunity to poverty to social injustice – perhaps we could have succeeded in having more accountable and responsible governance. Whether this would have prevented war is unlikely, but it would have maximized our chances at securing victory. Whether we will succeed in being such a society in the future largely depends on us.

And when we hear opinions, including mine, that the people have their share in this defeat, these are the circumstances taken into account. Blaming the people does not mean justifying the authorities, in the least. The latter is more culpable. The current government has made many mistakes, both before and during the war. The mistakes made by all the previous administrations are far more numerous and the people of Armenia are fully aware of this. One of the main arguments of the former regimes today is that they were able to maintain the status quo. True, even after the 2016 Four Day April War, they still managed to maintain the status quo. In other words, they managed to do the minimum necessary to keep the territories. As it turned out, this “minimum necessary” or “keeping it somehow” was not enough to keep what we had in the long run. It was necessary and possible to do much more than that. “Keeping it somehow” means we were walking along the edge of the abyss and we could have fallen at any moment. It was not necessary to “keep it somehow,” it was necessary to keep it well. The leaders of former administrations and those who served them, should have lived reasonably instead of amassing personal wealth at the expense of society, of the people who mostly lived in poor conditions. Indeed, in a war-torn state, there should not have been such privileged people with their clients and “bespredel” (from Russian “беспредел” — “lawlessness,” “arbitrariness”) with all the consequences that ensued. We lived in a society where state officials and family members of presidents were extremely rich. Had they acquired such a luxurious life through hard work, talent and sweat, it perhaps would have been tolerable. But we know all too well that, where there is smoke, there is fire. It is no coincidence that the former authorities (with some exceptions) have earned the label of “plunderers”; whereas, had they cherished and understood the value of statehood, it would have been possible to build a far more equitable state, an efficient army and adequate weapons and ammunition, which would have helped us avoid defeat.

Allied Relations

There are criticisms and complaints regarding Russia’s behavior, claiming the latter is not properly fulfilling its obligations as an ally to Armenia. There are complaints in particular that Russia did not support a more pro-Armenian agreement. One should not always expect the other side, even if they are an ally, to behave in accordance with one’s own interests. One should not always look at things from one’s own point of view, moreover in matters of geopolitics. Maybe the signed agreement is in Russia’s interests since it has succeeded to save some part of Artsakh, as well as deployed peacekeeping forces, a goal Moscow pursued ever since the First Karabakh War. Moscow has made it very clear that it is not going to pursue a pro-Armenian policy in Artsakh at the expense of good relations with Azerbaijan. All of Armenia’s international partners, including Russia, had made it abundantly clear that they would never support the status quo in Nagorno-Karabakh and that Armenia, sooner or later, would have to return the seven territories. For our country’s leadership to have expected anything else was arrogantly short-sighted. The political difficulty of selling that to the Armenian electorate was always the issue.

Instead of an Epilogue

There is one nuance in this tragedy. Was the Republic of Armenia defeated? If yes, then how is it that Armenia did not utilize its armed forces fully and why did the Su-30 fighter jets not fly a single sortie? Though there are some allegations that Armenian forces used the Iskander missile, it has not been officially confirmed. Did the military-political leadership of the Republic of Armenia have any fears? What were they? Or, in that case, why did the Armenian government purchase Su-30 fighters if they were not going to be used? We need a restraining and deterrent weapon against Turkey, and that issue was, and continues to be, resolved. The Russian military presence in Armenia is a restraining factor for both Turkey and Azerbaijan. Therefore, instead of buying a Su-30 jet or an Iskander missile, Armenia could have acquired weapons and armaments more practically applicable to the impending Artsakh-Azerbaijan war – be it Tor anti-aircraft missile systems, unmanned aerial vehicles or effective means for combating the latter, etc. If we had had great economic potential, we could have afforded to buy all these weapons. But that was not the case.

Consistent Passive Aggression and Realpolitik

Throughout the 2020 Artsakh War, the UK Government was mostly impotent, writes James Derounian. It instead has and continues to provide blind, sometimes tacit, support for Turkey directly and its ally Azerbaijan indirectly.

Read more12 Imperatives for Securing Armenia’s Future

We have a maximum of five years to significantly improve the security of the country along a number of fronts, requiring a collective will, sacrifices, trade-offs and personal choices unlike anything most of us have faced in our lifetimes, writes Raffi Kassarjian.

Read moreThe 2020 Artsakh War: What the World Lacks Now Is Leadership

The isolationism of former global powers in a fractured world has left vulnerable countries at the mercy of power-hungry regional players.

Read moreDignity

Isssue N2