Listen to the article.

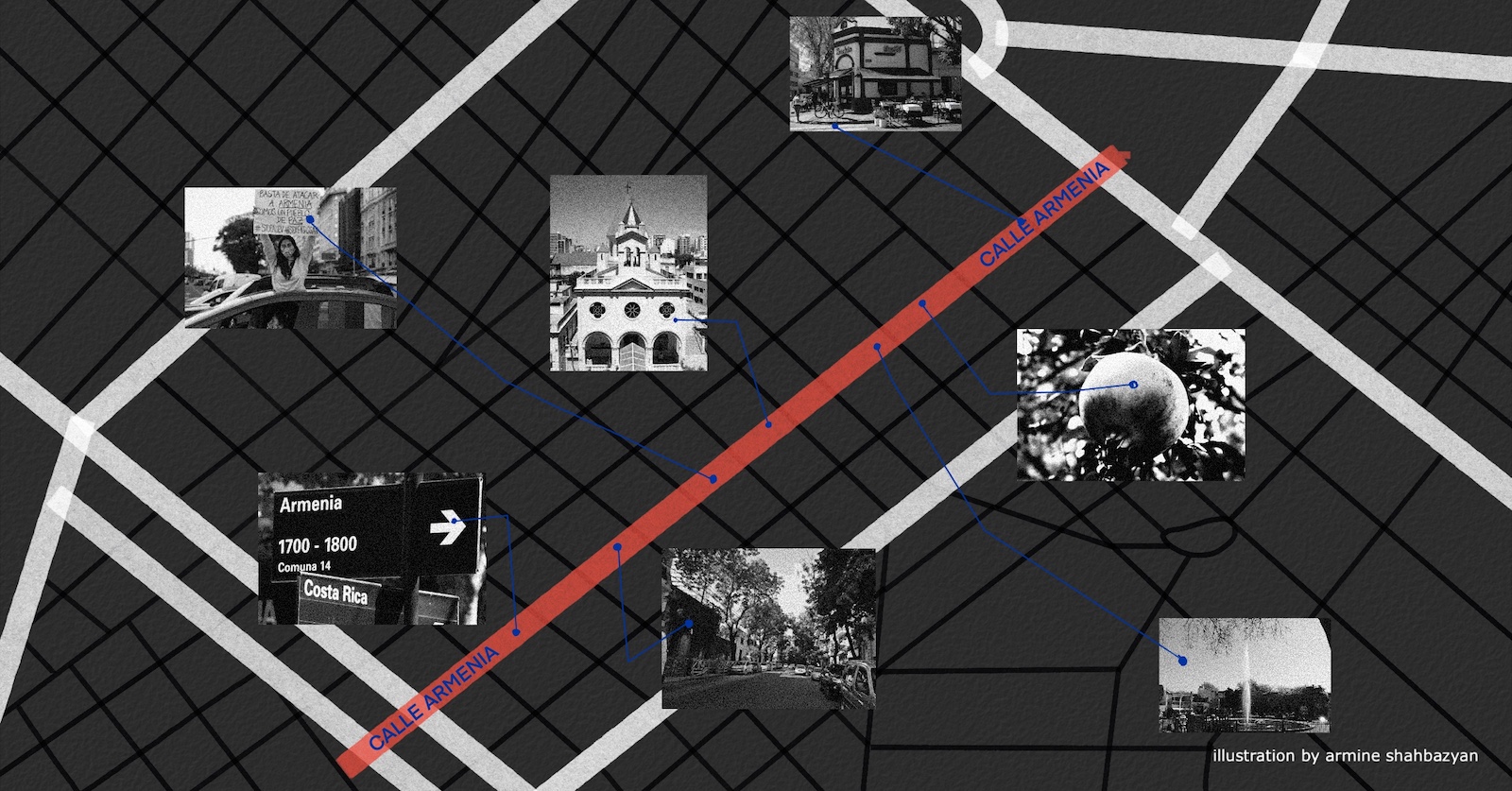

In the Palermo district, evening falls and lights glimmer along calle Armenia, where the flags of Armenia, Artsakh and Argentina flutter side by side. The restaurants display menus with familiar flavors, traditional community structures and compatriotic associations mark the Armenian presence in public space. We are in the heart of Argentine-Armenian life, where the Cathedral of Saint Gregory the Illuminator has been standing tall and dignified for 87 years. In Buenos Aires, there is no Armenian quarter, but there is an Armenian street.

A city shaped by European influences, Buenos Aires offers visitors a refined mix of Italian and Spanish cultures. The Argentine metropolis is also a major center of the Ashkenazi Jewish diaspora. It is here that Armenians have carved out their place and established their presence.

Argentina, situated on the edges of the Western world, ranked among the world’s top five economies at the dawn of the 20th century. It attracted many immigrants, among them the so-called “Turcos”—Christians from the Ottoman Empire, when Syria and Lebanon had yet to become sovereign states. Many were Syrian-Lebanese and Armenians, most often from Cilicia. The population, primarily of Italian and Spanish heritage, developed a softer Castilian Spanish accent and embraced Neapolitan culinary traditions. Within a few generations, Armenians in Argentina prospered economically and reached prominent positions. Entrepreneurs like Eduardo Eurnekian (Argentina’s sixth wealthiest individual) made a name for themselves, alongside artists, athletes (like tennis champion David Nalbandian), scholars, and scientists. Yet few rose in the political sphere—a notable absence, particularly as Turkish and Azerbaijani state agencies expanded their influence in South America’s Southern Cone.

For the diasporic traveller who engages with the community, two impressions arise in the porteño atmosphere. First, a relative sociocultural homogeneity, due to the very low number of Armenians from the Republic of Armenia—most who arrived in the 1990s later departed for the United States. Second, the effects of historical and geographical distance on perceptions of national identity. This raises a provocative question: if four generations have resisted assimilation without Armenia’s influence, can one sustain a diaspora without Armenia? Can an extraterritorial Armenianness, built from unifying myths, collective (or individual) trauma, folklore, and a longing for freedom, still exist today?

This question increasingly preoccupies Armenians from both the classic and newer diaspora, though they rarely discuss it openly. The relationship with the “real” Armenia fractured after the 2020 Artsakh War. A deep sense of abandonment persists, a silent pain from which people try to escape, finding the reality too difficult to face. They feel disconnected from the disheartening spectacle of Armenian political life and from Armenian elites in general.

We must have the courage to name things as they are, to accept reality, to confront it, and to move forward. Armenia is a transnation, a term I borrow from Khatchig Tölöyan, rather than a nation-state. The attachment of Armenians to their historic homeland has revealed its limitations since independence in 1991. Armenians from Armenia have emigrated en masse, and despite its liberation in 1994, Artsakh remained critically underpopulated given the potential of its territory. While many Armenians in Armenia dream of life in California, in the diaspora, the dream of return to Armenia—kept alive by the ARF’s Tebi Yerkir discourse—has failed to resonate. We must also remember the painful experiences of thousands of Western Armenians who, abandoning their comfortable lives to settle in Soviet Armenia after World War II in the name of patriotism, found themselves feeling utterly alien.

The diasporic experience, especially when compared with the Palestinian people’s resistance to remain on their land, invites painful, critical introspection. Can we exist without Armenian land beneath our feet, and if so, will we still be a nation? The answer is probably yes, provided that each Armenian accepts defining “Armenia” as wherever they are: be it Kessab, Aleppo, Bourj Hammoud, Marseille, Watertown, Glendale, Montevideo, or Lisbon.

Two Armenians who meet, as Saroyan once wrote, will recreate an Armenia. This may be true, but for this Armenia to take shape, there must be a story, a narrative that unites this deterritorialized nation around a purpose and spiritual elevation. The Jews survived exile through their laws and the enduring phrase, “Next year in Jerusalem.” The Armenians have yet to find a shared foundation beyond traumatic memory, reawakened by the 2020 war and its disastrous consequences. In this collective collapse, spiritual leaders have failed to develop a theology of exile or of genocide that could give both believers and non-believers meaning in all this suffering.

If one can maintain an Armenian soul without a homeland, can the opposite be true? Probably not. It is the soul, an invisible and mysterious essence, that explains this remarkable survival. The Armenian-Argentine experience, despite its imperfections, suggests this soul truly exists. Moreover, it reminds us that seeking meaning together matters more than dividing ourselves into “good” and “bad” Armenians.