Listen to the article․

In an ideal world, a student-centered approach forms the cornerstone of education, but this is often not the case, especially in Armenia.

This article focuses on several significant challenges encountered by Armenian university students studying law, examining both the overarching concerns regarding the delivery of legal education and specific deficiencies within the system. With a particular emphasis on the teaching of public international law, it seeks to shed light on critical aspects of Armenia’s legal education landscape.

The idea for this article originated from my firsthand experience as a law teacher at my alma mater, and was enhanced by contributions from current students, recent graduates, and colleagues from top Armenian universities with law programs. A short survey was also conducted to gather essential information from representatives of various universities in Armenia.

The aim, therefore, is not to praise or criticize specific Armenian universities, but rather to identify the main issues within Armenia’s legal education system. Therefore, specific university names will only be mentioned in exceptional cases.

In August 2022, I began my second LLM degree, this time outside of Armenia. That year was somewhat unique as I was concurrently teaching online as an international law specialist in a university in Yerevan. While studying in Europe, I observed the teaching methodologies of leading professors in the field, how they managed classroom instruction, noting both engaging and sometimes less engaging teaching approaches.

“You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view.” This quote from Atticus Finch in Harper Lee’s Pulitzer-awarded novel “To Kill a Mockingbird” guided me throughout my LLM journey. It helped me understand the issues law students faced in modern Armenia. This essay will thus focus on student’s perspectives, shedding light on the significant educational issues they face both inside and outside the classroom.

Teaching Is Not Just a Vocation

While teaching can be inspiring, it also requires a specific skill set. Many universities in Armenia are keen on inviting lecturers who are known in their respective fields. Law departments often highly value judges, prosecutors, prominent attorneys, lawyers from the ministries of Foreign Affairs and Justice, and individuals from various international and non-governmental organizations. Being a well-known “reels lawyer” on social networks can also influence potential hiring. However, prestige does not always equate to quality teaching. Success in a courtroom or diplomatic negotiations does not guarantee success in a classroom, and being popular on Instagram does not secure effective teaching.

Lectures for law students at many Armenian universities typically require an 80 to 90-minute speech delivered to a large audience of over 50 students. In some cases, this size can exceed 70 students, creating significant pressure on the lecturer. Moreover, since obtaining a university degree in general is considered important in Armenian society for various subjective reasons (most frequently based on family expectations or strong societal pressure to pursue higher education), lecturers often encounter students with minimal interest in studying. This can negatively impact the lecturer’s level of engagement, which can increase frustration among students, leading to a decline in the rapport between the lecturer and students.

Teaching, often akin to public speaking, demands certain skills and competencies. Given that not all law professors or lecturers possess strong public speaking skills and considering that lectures can run for nearly an hour and a half, students may eventually grow tired and lose focus. To mitigate such issues, it is crucial for universities and educational institutions to provide training in public speaking and related skills for law professionals.

Standard Class Schedule and Lack of Communication

The lecture-seminar style is not always sufficient and many foreign universities no longer emphasize the traditional lecture-seminar structure. When they do, seminar participation is generally mandatory and contributes to the student’s final grade. Armenian universities usually follow this classic model. However, out of the usual 8 to 16 seminars per semester, sometimes only one is necessary to qualify for the exam. Some universities may deduct points for absences, but participation is not a mandatory requirement for the final grade. This leads to situations where a teacher might only encounter a student at the final seminar, if at all, with no significant impact on the grade, still allowing the student to pass the exam.

Another noticeable problem is poor communication between lecturers and their teaching assistants. Out-of-class communication is often not emphasized, and lecturers usually do not share details of the latest lecture with their TA. As a result, the seminar and lecture formally complement each other, but in reality, they operate on two separate tracks. This approach does not benefit students and complicates the teaching process for the staff.

Despite the issues mentioned, survey results show that most students are comfortable with the lecture-seminar format, although they identify several concerns related to it.

Limited Impact of Student Reviews on Teacher Employment and Salary

Students have a limited role in influencing a teacher’s career at university. The only situation in which they could potentially impact a teacher’s appointment is through the end-of-semester evaluation. However, in leading Western universities, this evaluation is seldom mandatory, and the administration sometimes overlooks it. My experience in Armenia is much worse. Since 2019, I have only received two evaluations, with less than half of the students participating in the survey each time.

Typically, the performance assessment of faculty in some universities is based on the results of scholarly research conducted throughout the year, conference participation, and their syllabi, rather than on student feedback and teaching quality. On the other hand, some universities do not conduct such evaluations at all. Unless a serious issue arises concerning a teacher, they may continue to teach at the same institution for decades.

Evaluation outcomes can have both positive and negative aspects. Sometimes, teachers perceived as demanding by students can receive a low rating. Finding a balance is not easy, but a certain margin of error should not fully devalue the survey.

Old-fashioned Teaching Methods

While most survey respondents were more or less satisfied with the classic lecture-seminar structure, one major barrier to creating an engaging classroom atmosphere is the “old-fashioned” way of teaching. Traditional methods are not inherently negative, but as education evolves, students are looking for more interactive and informal teaching methods. Many students suggested methods like debates, moot courts, interactive quizzes, case studies, and problem-solving tasks during classes, particularly seminars, would be beneficial and increase their interest in lessons. Modern tools such as the Socrative app, which is both interactive and useful for certain teaching and learning tasks, could also be used. However, some lecturers may not be willing to introduce or implement these new teaching methods, and their approach may not always be in step with the times.

Lack of Textbooks and Limited Library Collection

A teacher’s reliance on a specific textbook can significantly hinder the quality of education. Notably, this issue isn’t unique to Armenia but is also prevalent abroad. It becomes particularly critical for certain subjects in Armenia, where there are no alternatives. For instance, no textbooks on public international law have been published in Armenian since 2002; that was the year that the only textbook on the subject in Armenia was published. Consequently, discussing specialized textbooks in various branches of public international law is virtually pointless as there are so few.

In 2021, a manual on international criminal law was published in Armenian, and there are a few ongoing attempts to translate textbooks into Armenian in different fields of international law. However, these efforts are exceptions rather than the norm. The situation is slightly better in such fields like criminal law, civil law, and other areas of national law, though the number of books published annually is still relatively small.

As mentioned, students studying public international law at Armenian universities often struggle with language barriers when learning the subject in Russian or English. Alternatively, they use outdated textbooks, which fail to provide insight into modern trends and current contexts in international law.

Survey participants also highlighted issues with university libraries. Nearly all respondents, except those affiliated with the American University of Armenia, noted serious problems with library collections, particularly in prioritizing the purchase of contemporary textbook editions. Some universities also lack subscriptions to leading online law journals, especially those focusing on international law. For studies in public international law, it is also crucial to have ample English-language resources, as English is the predominant language for international research in this field.

Lack of Practical Skills

The surveyed students primarily raised concerns about the lack of practical skills provided by education programs and law teachers. Law schools tend to focus more on imparting knowledge than on equipping students with practical skills, which can result in a lack of readily employable lawyers. This issue could potentially be mitigated through well-organized internships. However, in reality, these internships often act as a formality where the trainee and the internship manager meet only to sign the student’s internship report.

The situation appears even more challenging from the perspective of public international law (PIL) students. Opportunities for hands-on experience in PIL are limited, typically confined to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Justice, and the Office of the Representative on International Legal Matters. Given the limited openings and the heavy workload of employees, not every student interested in international law secures a meaningful internship during their studies. Consequently, fresh graduates, despite their diplomas, often find themselves starting from scratch, as mere theoretical knowledge proves insufficient for working in the field.

Faculty Lack of Interest in Research Papers

As the global landscape evolves, so does international law. It not only requires updated textbooks, but also necessitates the exploration of new research topics. Subjects once considered relevant are now overshadowed by more urgent issues, highlighting the dynamic nature of this field.

However, this is not usually the case in Armenian educational institutions. A review of term papers from second or third-year law students at Armenian universities reveals a repeated focus on the same issues year after year. What’s the reason behind this? One perspective suggests it’s a matter of tradition. Almost every department within a law faculty maintains a “sacred list” of term paper topics. This list is seldom updated, and only the most daring students attempt topics not on the list. Given that word of mouth is still effective, other students often hear about this and are reluctant to make additional efforts.

Another significant challenge is the insufficient attention faculty give to term papers. These papers should form the basis for subsequent graduate work at the bachelor’s and master’s level. Instead, coursework defense often appears perfunctory, with the admissions committee rarely delving into each student’s work. Moreover, supervisors frequently overlook students’ term papers, focusing primarily on the final thesis paper. Consequently, graduates may lack essential skills, sometimes even such basic skills as using the track changes feature in Word, due to the absence of constructive feedback in this format from their supervisors.

Lack of Effective Ethical Codes for Teachers

Many students have raised concerns about the behavior of their lecturers. In European universities, even a seemingly harmless joke could trigger an official investigation with potential serious consequences for both the teacher and the student. However, in Armenian universities, faculty are often permitted more leeway than students, occasionally resulting in an abuse of their position. Although this is not a widespread issue, it is concerning enough to warrant attention.

Another negative aspect is the politicization of lecturers. Given that university lecturers often serve as role models for students, their behavior can greatly influence students’ conduct and perspectives. Even though academic freedom is crucial at universities, it should not be conflated with or used as cover for political propaganda or hate speech.

Students often don’t know who to turn to when they find a lecturer’s behavior inappropriate. Thus, it’s crucial to establish a code of ethics and a point person to oversee relations between students and teachers and conduct necessary investigations if needed.

Lack of Motivation

The last concern is directly related to teaching public international law. There was a surge of interest in international law, specifically international humanitarian law, during the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War. However, subsequent events sparked debates on the effectiveness of international law.

“International law does not work” is the most common remark I encounter when I start teaching a new class. To some extent, this is true when evaluating international law’s effectiveness in sanctions. The UN Security Council frequently faces paralysis due to countries with veto power. States are unwilling to bring certain disputes to the International Court of Justice, and the International Criminal Court’s procedures for prosecuting international crimes are far from effective. In such a challenging reality, faith in international law is gradually diminishing, with students being no exception.

This issue demands careful consideration. As an instructor introducing the fundamentals of international law, it’s crucial to manage student expectations about this legal system to avoid creating unrealistic expectations.

Given the limitations of this article’s scope, not all existing issues in Armenian law departments could be fully addressed. Therefore, I invite all interested researchers, practitioners, and students to share their ideas and offer their insights to finding solutions to these pressing challenges.

Opinion

Orphan to Internationalist: The Legacy of Missak Manouchian

Missak and Melinee Manouchian made history as the first foreigners to be inducted in the French Pantheon for their role in the fight against Nazism. The pantheonization sparked a wave of romanticism, glossing over the complexities surrounding foreign participation and the ensuing quest for recognition.

Read moreIs Armenia a Nation-State?

Is Armenia a nation-state? While the answer may seem obvious at first glance, upon closer examination, the question's significance becomes apparent, writes Tigran Yegavian.

Read moreBeyond the Drone Hype: Unpacking Nagorno-Karabakh’s Real Lessons

The 2020 Artsakh War served as a stark reminder of the transformative role that drones are playing on the modern battlefield. Davit Khachatryan argues, however, that the overemphasis surrounding drones requires a more sober and critical analysis.

Read moreTowards a Franco-Armenian Strategic Partnership?

The Coordinating Council of Armenian Associations in France recently hosted its annual dinner in Paris against the backdrop of heightened geopolitical tensions and concerns over Armenia's security. The focus shifted to the role of France in implementing deterrence measures and sanctions against Azerbaijan.

Read moreThe Eagle and the Trident

With Zelenskyy’s potential visit to Armenia in the coming days, Justin Tomczyk writes that Ukraine’s experience over the past two years can provide insights into how smaller democracies must fight against their larger, authoritarian neighbors.

Read moreLenin in the Periphery: Self-Determination and Its Discontents

Over 30 years ago, a statue of Lenin towered over the heart of Yerevan until it was dismantled. The recent centennial of Lenin’s death went mostly unnoticed in Armenia but it might have sparked reflection on Lenin’s impact during the Sovietization of Armenia and how his definition of self-determination has had consequences on contemporary geopolitics.

Read moreEVN Report

Media Festival

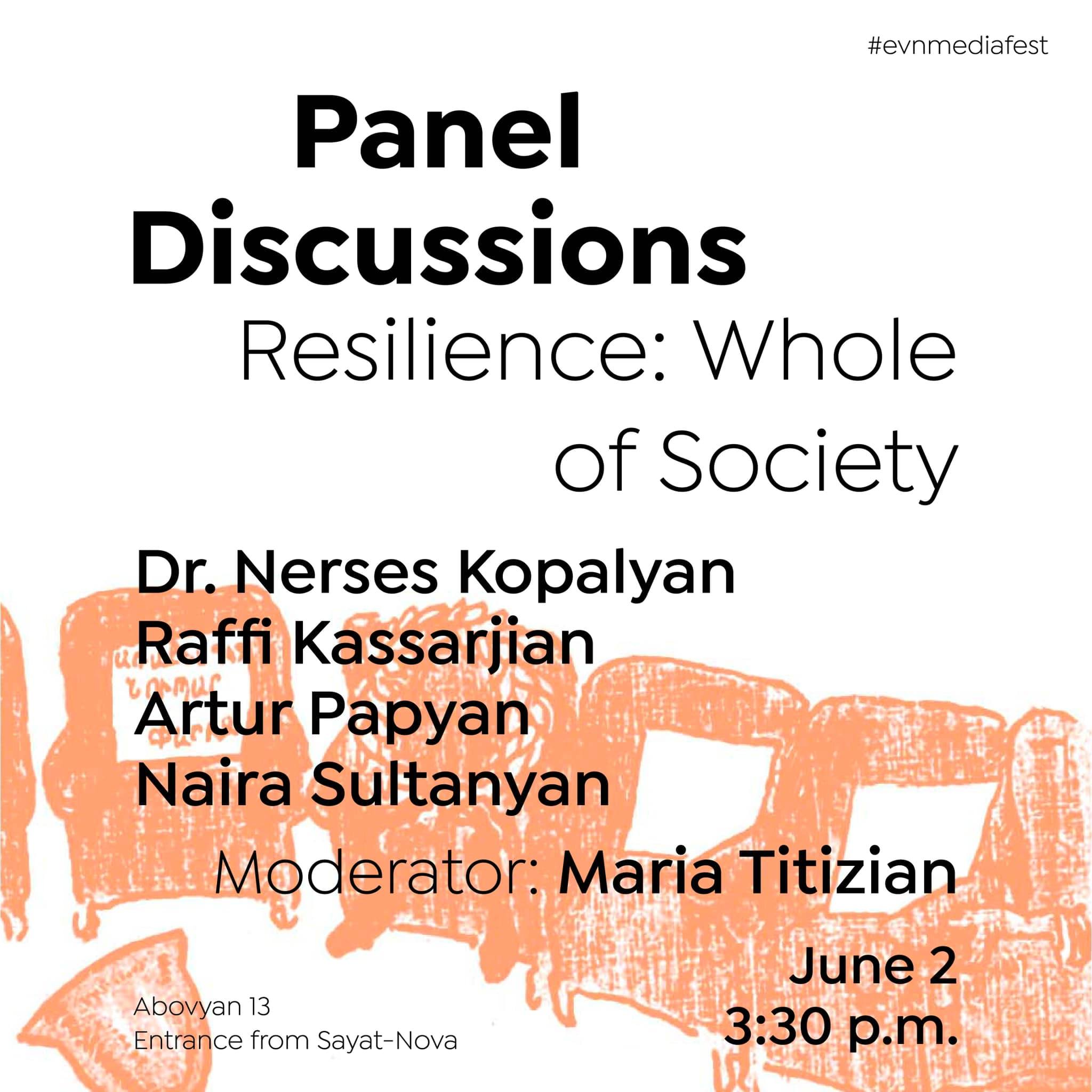

When surrounded by aggressive neighbors, smaller democratic states evolve by integrating their social and governmental structures into a comprehensive security system, bolstering their resilience. This holistic approach, involving both state and society, strengthens their ability to withstand threats and navigate through crises. This panel, which includes representatives from the business community, IT sector, civil society and academia will look at the mechanisms through which societal structures can be mobilized and harnessed to increase resilience during times of peace and amid security threats. The panel discussion will be held on May 2, at 3:30 pm.

Register here.

See the full Program.