The “Velvet Revolution” in Armenia has turned Armenia-Diaspora relations upside down. The new leaders in Armenia aim to organize massive repatriation, use Diaspora human resources to develop Armenia’s economy, and even propose to include them in political and administrative reforms. On the other hand, there are voices critical of Diaspora organizations and individuals seen as having supported the old regime.

This article is an investigation on this gap between expectations placed on the Diaspora by the new leadership of Armenia, and criticism of past activities. It goes beyond this gap by asking whether it will be possible to revolutionize the relations from uni-dimensional, to a real, two-way cooperation.

The Law of Unequal Relationship

I would like to start with my previous observations about the intrinsic tensions in Armenia-Diaspora relations. The problem was not limited to the old regime’s interest in the Diaspora, limited to cash flows and lobbying activities. I raised the fact that Diaspora organizations active in Armenia had limited impact on the country – their political impact was negligible, while financial investments could not solve the massive social-economic problems. Yet, I argued, this continuous focus on Armenia came at the price of neglecting Diaspora communities at a time when those communities were in great need for new investments, institutions and networks. Here is a quote from 2004: “The enormous effort by the diaspora to support Armenia has taken funds away from its community organisation just as its identity was starting to change under pressure from new migration trends and in a decade of globalisation. This has weakened traditional Armenian community structures, such as the parties, church and schools. Though the overall influence of the diaspora is increasing in Armenia, its impact on political, social and economic decision-making remains limited.” [1]

What lacked in Armenia-Diaspora relations, even after a quarter of a century of independence and six pompous conferences, was basic strategic thinking. In fact, Diaspora organizations precipitated to work in Armenia without grasping the complexities of post-Soviet changes; yet, choices made in the early 1990s are still valid and many are guided with the same basic concepts. In March 1988, a month after massive demonstrations demanding the reunification of Nagorno Karabakh with Soviet Armenia had begun, the three traditional Diasporan parties released a joint declaration criticizing the popular mobilization. They feared an uprising in Armenia would weaken ties with Moscow and expose Armenia to Turkish threats; three years later, the ARF-Tashnagtsutyun proposed actor Sos Sargsyan as its candidate for the October 1991 presidential elections. In other words, while in 1988, Diaspora parties could not grasp the political changes taking place, yet by 1991 they had the ambition of leading the country, hence the presidential candidate.

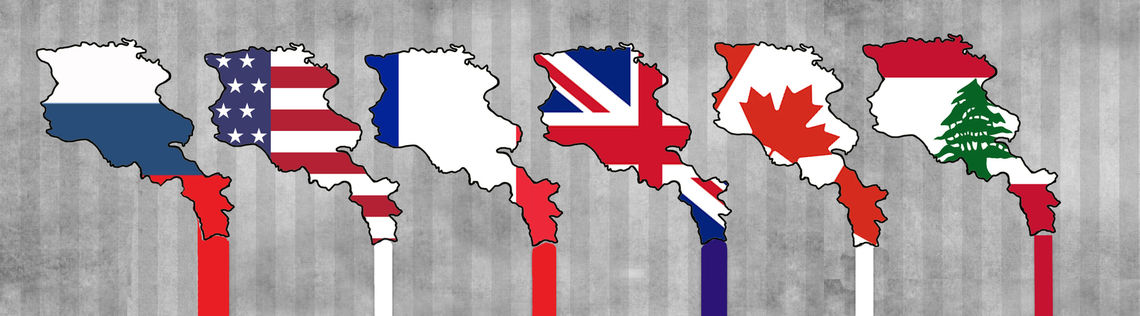

Other Diasporan structures and individuals – from AGBU to Kirk Kerkorian – massively invested in Armenia as though replacing Armenia’s social services, infrastructure renovation, or cultural ministries. Focusing on Armenia came at the price of neglecting the Diapsora. Meanwhile, the Diaspora was going through tectonic changes comparable to the 1920s where it needed – and lacked – massive investments to provide an institutional framework to new communities, formed by displacement of the traditional Diaspora from the Middle East to Western countries, but also because of migration of some two million Armenians from the Caucasus to Russia, Eastern Europe and North America. This lack of investments resulted in impoverishment of Diasporic institutions – media, schools, culture – and the spread of a pessimistic view on the future of the Diaspora. [2]

Will the changes in Yerevan provide an occasion to review Armenia-Diaspora relations?

Revolutionary Expectations

Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said during an interview that it is his objective to “organize a great repatriation” and added: “The potential of our compatriots is useful [for Armenia] not only in the economic and cultural sectors, but also in governance and public administration.” Moreover, Pashinyan said that the greater implication of the Diaspora in the public life within Armenia “could constitute the first step towards this great repatriation.” Armenian President Armen Sarkissian went a step further, when, answering through email to my questions, mentioning, “Armenia’s role in preserving national identity (azkabahbanum) in the Diaspora.” In other words, the expectations are as great as the enthusiasm generated by the political changes within Armenia. On the other hand, there is an increasing questioning of the role played by the Diaspora. In the same email exchange, President Sarkissian writes about the “public demand to review the state of affairs” in what concerns Armenia-Diaspora relations. Arsen Kharatyan, an advisor to the prime minister said, “We should move beyond formal elite relations to establish horizontal ties.”

Deputy Minister of Diaspora Babken Der Grigorian is even on record saying that “just like in Armenia [where] we had a problem of legitimacy, with the same measure there is an issue of legitimacy in the Diaspora.”[3] This politicization clearly intends to see a more active Diaspora intervention in the political life of Armenia. It might also mean a more active intervention from Yerevan inside the turf of Diaspora organizations. Nevertheless, the way the two entities (Armenia and Diaspora) will intervene in the political matters of each other is not clear and could possibly create a number of frictions.

The nerve centre of this policy shift is the Ministry of Diaspora. For the moment the new and young minister, Mkhitar Hayrapetyan, seems to be busy uncovering inefficiency and corruption under the previous administration. But what is the strategic orientation of the new minister? In order to discuss those changes I wrote several times to the Minister and to Deputy Minister Babken Der Grigorian, but received no answer. What follows is based on secondary sources and media reports. One report that circulated was the idea of having a second chamber of parliament composed of Diaspora delegates.[4] Yet, the danger of such a proposition is evident: it could take Diasporan communities hostage of Yerevan’s foreign policy choices. It could also paralyze Armenia’s foreign policy not to endanger politically institutionalized communities abroad.

It is also not clear in what way “new Armenia” intends to intervene in Diaspora affairs, nor what political role it imagines to give to the Diaspora within Armenian politics. It is one thing to include some Diasporan experts as technocrats within Armenia ministries, it is another to demand Diasporan actors to have a political, and even a moral stand about such complex issues as corruption or electoral fraud inside Armenia. We need to look beyond the current revolutionary enthusiasm to see the potential friction and structural inconsistencies. Any clash between a major Diaspora organization with the rulers in Armenia could have dire consequences on the weaker side. So, whoever the ruler in Yerevan is, Diaspora organizations have a natural tendency to try and cooperate, regardless of political or ideological preferences. Moreover, in the last decades Diaspora organizations largely behaved as Yerevan’s lobby groups abroad. Yet, this is incompatible with legal and moral struggles concerning Armenia’s internal polarizations. Imagine under Kocharyan’s or Sargsyan’s tenure, Armenian lobby structures abroad approaching international bodies asking for a pro-Armenian position, genocide recognition, Karabakh conflict resolution, humanitarian or development funds, while simultaneously asking them to pressure Yerevan to secure electoral transparency or denouncing corruption in state bodies. Lobbying and political militancy are two distinct activities, and a choice should be made which road to follow. Politicization, therefore, comes with a price, and with numerous risks.

Conservative Diaspora Institutions

In the meantime, political institutions in the Diaspora seem frozen in their choices from the early 1990s. Whether those choices are still valid or not, we do not know, as there is neither a policy debate, nor a serious effort of communication. Yet, not only are the new Armenian leaders increasingly challenging traditional Diaspora institutions, but their own constituencies are also questioning them and their policy choices.

Referring to Diaspora institutions, Vahe Keushguerian, an entrepreneur who was recently appointed advisor to the Minister of Diaspora said, “In hindsight they will justify” their previous position. “Diaspora cannot get credit for the Velvet Revolution; except for a few individuals, they were part of the conservative scene,” he said and added: “Armenia is much more forward looking than Diaspora Armenians.”

“AGBU has not been with the authorities but with the state,” Talar Kazanjian, the executive director of AGBU in Yerevan said. “No matter who is in power, the AGBU is always with the Armenian government and statehood.” Yet, it is not always evident to differentiate a specific administration from statehood, as state institutions in Armenia do not enjoy autonomy from political leadership. Kazanjian added that Armenia has evolved to become a sort of a centre for the Diaspora: “Our Diaspora is Armenocentric, with its good and bad sides. In today’s reality Armenia is the heart of global Armenians.” It should be noted that AGBU’s contributions to Armenia are significantly lower than its allocations for the Diaspora given its historic obligations.

Kazanjian echoed concerns about Diaspora institutions and the challenges they face. “What is the solution? It’s complex,” she said. “One thing is for sure that in order to survive, Diaspora institutions need to professionalize.” The decline of the education level of Armenian schools abroad is of special concern. “The choice today is between quality education and Armenian identity,” she noted. “People take the issue of schools very seriously, because there lies the nucleus of Armenian identity.”

As we are discussing these issues, more Diasporan schools are falling apart. Just in the last few weeks there are rumours circulating about the possible closing down of the historic Getronagan Secondary School in Istanbul in order to save 100,000 EUR yearly, and unite it with Esaian School,[5] and the closing down of AGBU’s Hovagimian-Manougian school in Beirut. In Syria, student numbers in Armenian schools has decreased by as much as two-thirds since the beginning of the conflict, raising a number of questions about the survival of its seven Armenian schools.[6]

Giro Manoyan, who heads the ARF’s Armenian Cause office based in Yerevan, does not see any justification to label his party as “pro-regime” during the decade when Serzh Sargsyan was in power. The ARF left the government coalition in 2009 because of the Armenia-Turkey negotiations and joined it once again only in February 2016 following the constitutional changes. The ARF also “opposed the privatization of the pension system, which brought down the government of Tigran Sargsyan in 2014” and supported the constitutional reforms of 2015 which transformed Armenia from a “semi-presidential system to a parliamentary one, separating the branches of power” when other opposition parties voted against the reforms. Yet, Manoyan sees a special role for the ARF in what concerns foreign policy, for which the party had to work with the Sargsyan administration, be it Syria, Artsakh or the Armenia-Turkey protocols.

Manoyan rejects claims that the ARF has become a party with two political cultures, one in Armenia and the other in the Diaspora. Yet, some have interpreted the way Apo Boghigian, the editor of the ARF daily Asbarez based in California, was kicked out from party ranks as evident tension between its Armenia branch and Diaspora cadres.[7] Many ARF militants have been critical towards the way the party supported the candidacy of Serzh Sargsyan to become prime minister. The party leadership seems to have preferred to silence dissent rather than to engage in a critical debate, as the punishment of fourteen Lebanese militants for their dissent illustrates.

New Diaspora Coming Home

Russia is home to the biggest Armenian Diaspora community, yet its community infrastructure remains comparatively weak. Russian-Armenians are a multi-layered population who have migrated to Russia throughout centuries, coming from different Trasncaucasian towns and villages. Their numbers are estimated at two million,[8] including among them many who left Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia since the collapse of the Soviet Union. When new Armenian leaders talk about repatriation, they probably think about this population, rather than the “old” Diaspora originating in historic West Armenia.

The Russian-Armenian Diaspora has its own specificity, and no one articulates them better than Vartan Marashlyan; born in Yerevan, lived in Russia, Marashlyan decided to return to Armenia where he assumed the post of deputy-minister of Diaspora, before becoming co-founder and director of Repat Armenia.[9] He explains how culturally Russian-Armenians are different from the traditional Diaspora. “Armenians who move to Russia do not think that they have gone to a new country, because of the knowledge of the language and the culture. Moreover, they think they stay close to Armenia” and make no special effort to preserve the language explains Marashlyan. “The integration in Russia happens quickly; so does assimilation,” he concludes. In recent years in Russia new Armenian organizations have emerged. The first type is centred around “businessmen and their major motivation is to use their status to defend their social and economic status.” The second type are networks centred around topical interests. Armenia receives the equivalent of $2 billion in yearly remittances, of which 90 percent comes from Russia. The negative side is that the sums are donated and consumed rather than invested in economic development.

In the past Russian-Armenians had looked down on their country of origin as a poor, backward place. The “Velvet Revolution” changed that; it had a “wow effect” according to Marashlyan. Now, Armenia seems to be developing a political culture that is more attractive than Russia’s, in spite of its economic hardship. Marashlyan wants to see up to thirty thousand Armenian kids come to Armenia every summer to learn Eastern or Western Armenian. “They should come not only because it is Armenia, but because education here is of high quality; plus it is fun and cool.” Keushgerian expressed a similar idea concerning repatriation: “It should happen because Armenia has a vibrant economy, not for patriotism.”

The investment of Diaspora individuals inside Armenia is increasingly visible. TUMO centre with its futuristic technology is one, the newly opened SMART Centre in far-away Lori region is another.[10] Those are the tips of icebergs of thousands of initiatives that are changing Armenia-Diaspora relationship and identities. “I don’t consider myself spurkahay anymore,” Sara Anjargolian, director of Impact Hub Yerevan told me. “I have more in common with someone living in 3rd Mas [a suburb of Yerevan] than someone who lives in Pasadena.” Many like her who are living in Armenia feel that “we do not need the old institutions anymore, we can establish direct connections.”

Marc Grigorian, the Director of Public Radio, takes the idea further. He says that in the 1990s, Diaspora institutions were functioning in a vacuum, and therefore their input in Armenia was important. Today, things have changed as individual initiatives have taken over in importance what traditional institutions such as the AGBU could have as impact. “In the future there will be an important increase in Russian-Armenian charity input into Armenia, which will further decrease AGBU’s importance,” he concludes. This is a reasonable expectation, as 8/10 richest Armenians made their fortunes and live in Russia, and only two come from the traditional Diaspora.[11]

Armenia-Diaspora: One-way Relationship?

Six Armenia-Diaspora conferences were organized in the past marking an incredible achievement: to avoid any substantial discussion of the real problems between the two sides.[12] As Armenia’s leadership aims to change the relationship, more than ever we are confronted with the lack of leadership, lack of policy debate within the Diaspora. We are left with a structural power imbalance between an active Armenia with a dynamic leadership, with passive Diaspora organizations that fail to field its own leadership. Let us face it, Armenia has many problems to solve, and whatever is said in Yerevan, Diaspora relations hardly make the top-ten list of urgent issues. Without an articulate Diaspora with competent leadership, Armenia-Diaspora relations will remain one-way affairs, where Yerevan will continue to attract various resources from the Diaspora, but without the opposite input. The structural problems of Diaspora communities will only deepen.

In case traditional Diaspora institutions are unable to produce critical thinking – the first step towards strategic vision and leadership – they might soon be overtaken by a new generation of activists, philanthropists and professionals who want to engage in changing Armenia-Diaspora relations, and who consider the traditional institutions as obsolete.