There are protests on the streets of Yerevan again. This time it is a student protest against a controversial bill on mandatory military service, which effectively abolishes draft deferment for university students. The protests are quite remarkable, as this is the first major protest in Yerevan since last year’s July events. This is also a students’ protest, something which does not happen in Armenia that often. While students in most countries are considered to be socially active and prone to protesting, this has not been the case in Armenia. True, every major protest includes some students, but the phenomenon of student protest per se has not been that widespread so far. In fact, the most serious cases of student protests in modern Armenia’s history have occurred precisely in relation to the issue of military draft.

In 2004, probably the most powerful student protest movement took place in Armenia, organized by a group that called itself “For Development of Science,” a name adopted by today’s student protest as well. Ironically, some participants of these earlier protests, who went on to become prominent RPA members, are today on the other side of the argument.

Abolishing the Deferment: Why Now?

This time the protests began as a response to the controversial bill, adopted by parliament in the first reading in late October, which effectively removes the practice of deferment from military draft for university students. Instead, the new bill provides an option for students to sign a contract with the Ministry of Defense, which would allow them to receive deferment for completing their studies, but after that they would have to serve three years instead of two. Thus, it abolishes the practice, when those students who went on to post-graduate level studies and proceeded to work in universities or research institutions were relieved of military service altogether. It also means that most young males will have to choose between serving two years at the age of 18 or serving three years at a later age, in case they opt for the contract with the Defense Ministry (it is not yet clear how the system of contracts will work in practice).

Defense Minister Vigen Sargsyan and the ruling Republican Party argue that the previous practice of deferment for university students was discriminatory, created social injustice and opened opportunities for corruption. What is probably more important, the military lost potential recruits as a result of the determent: the Ministry of Defense claimed that the majority of students who received deferment never proceeded to serve in the army, even after completion of their studies.

There is another important argument in favor of the bill: In the last ten years Armenia has experienced significant loss of population, mostly due to emigration from the country, and it means that in the future the Armenian military may face lack of recruits. However, the ruling party avoids stressing this factor, since this would also mean accepting responsibility for emigration and the socio-economic difficulties that caused it.

In fact, this is not the first attempt by Armenia’s authorities to introduce military draft for university students. The first attempt took place back in the 1990s, when it was abandoned due to student protests and opposition from some members of the government. Another attempt to end the deferment for university students took place in 2004, when it lead to probably the most powerful student protest movement in Armenia, organized by a group that called itself “For Development of Science,” a name adopted by today’s student protest as well. Ironically, some participants of these earlier protests, who went on to become prominent RPA members, are today on the other side of the argument.

The Elephant in the Room: Why are Students Protesting?

The critics of the new bill worry that abolishing the deferment could be detrimental for development of education and science in Armenia. They argue the practice shows that many young men returning after military service do not show interest in continuing their studies. While this statement may be open to debate, it is true that the majority of younger professors and scientists currently working in Armenia, have been beneficiaries of the deferment from military service. So have many politicians, government officials, journalists, artists, other members of Armenia’s political and intellectual elite.

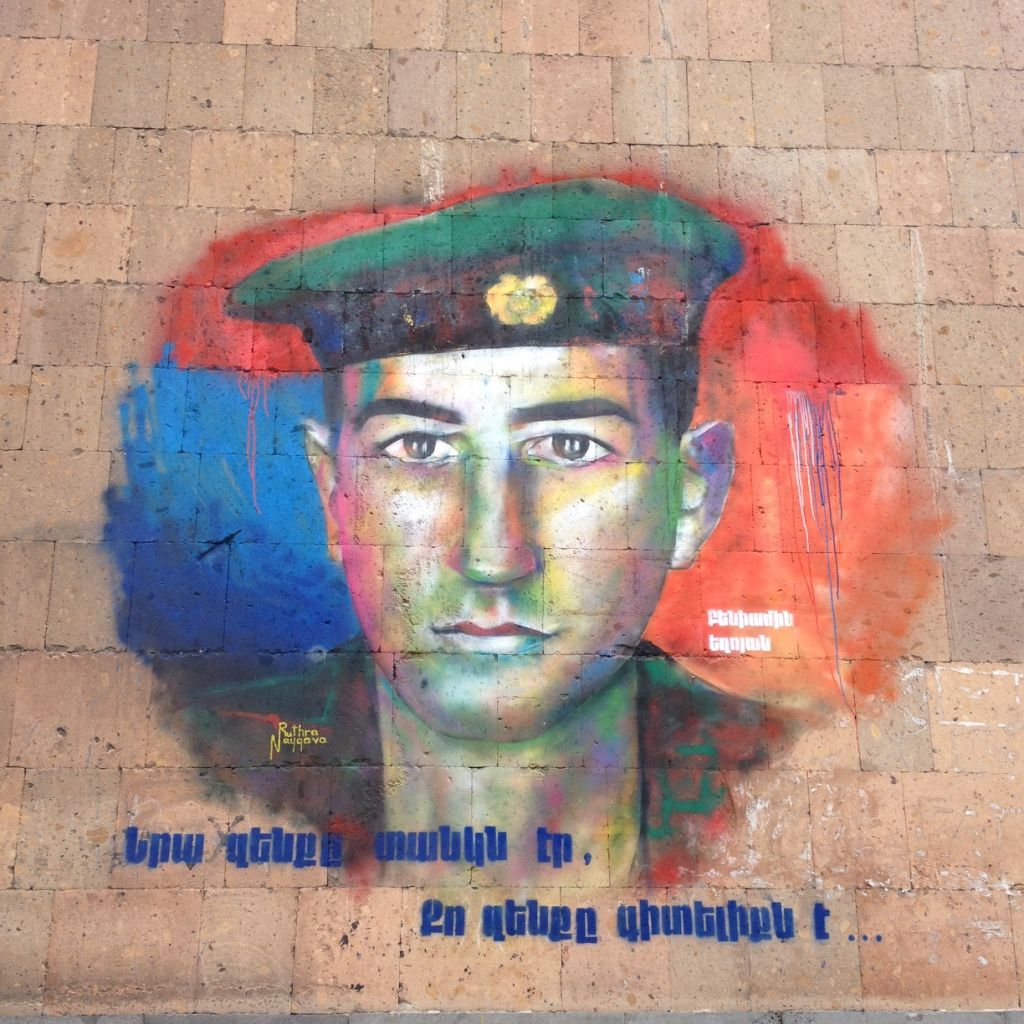

A mural of Benjamin Yeghoyan (b.1992), a hero of the April, 2016 Four Day War, on the wall of Yerevan State University. The text reads, “His weapon was a tank, your weapon is knowledge.”

Government critics point to the hypocrisy of some ruling party members, who are today supporting the bill, but who have avoided military service by using the determent option in the past. Besides, the bill’s critics add, it will not solve the issue of corruption: those who have used corruption to avoid military service in the past will continue doing it, using other paths. As opposition lawmaker Nikol Pashinyan has argued, the majority of those who do not serve in the army are exempted due to medical reasons: hence the biggest corruption risks are in this field rather than in the universities. In addition, even Republican Party MPs agree with concerns that abolishment of the deferment could push more families to emigrate, in order to shield their young sons from the perspective of serving in the military at the age of 18.

The elephant in the room in these discussions is something that all Armenians know, but few politicians address openly. The members of the ruling elite, composed of government officials and “oligarchs” are essentially a privileged caste, de facto exempt from the obligation of military service. Obviously, this law is an unwritten rule, but its informal nature does not make it less powerful. Young members of the elite have various ways of either avoiding military service altogether, or serving in privileged conditions (e.g. in the Ministry of Defense or in Armenia’s embassies abroad). In some cases this is achieved through their parents’ connections, in other cases through bribes. The ultimate result is the same: children of the ruling elite very rarely find themselves in the trenches. In the absolute majority of cases, those who have lost their lives or have been injured in the fighting on the border come from disadvantaged groups in society.

Against this background, the deferment provision gave a chance to those with little money or connections to postpone their military service or even avoid it altogether, provided they devoted themselves to a life in academia. Of course, it was an option, which only a minority of young men were able to pursue. Moreover, for those young men who came from rural areas and other disadvantaged backgrounds even this opportunity was a luxury, hard to attain. And in many cases, it was this “academic” path to avoiding military service that was used by the members of the elite. But, with all those reservations, for a large number of young men, especially those from the ranks of the “urban middle class” and “intelligentsia,” the deferment offered a choice, which made it easier for them to reconcile with some of the injustices of life in Armenia (it is important to note that terms like “middle class” or “intelligentsia” have a quite different meaning in Armenia, compared to developed Western countries; they reflect occupation and lifestyle rather than income levels).

Not everybody used this option, but at least many young people felt they had a choice. The new bill takes away this choice. It is a bitter pill for many young Armenians, and it is all the more difficult to swallow, since the ruling elite’s de facto privilege of not having to serve in the military will most probably remain unharmed.