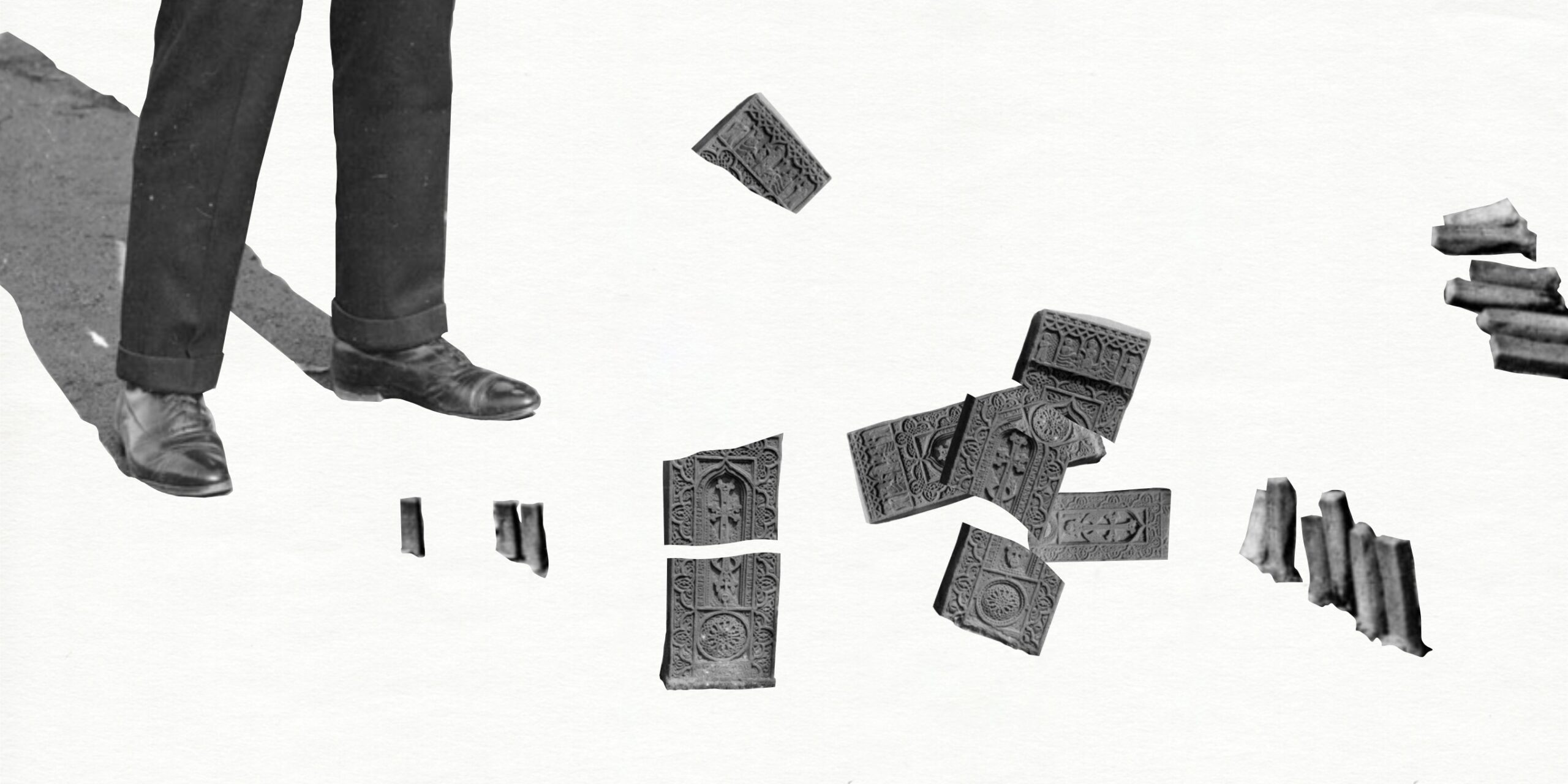

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

Members of the European Parliament (EP) strictly condemned Azerbaijan’s attack against Artsakh in the fall of 2020. While a ceasefire was supposed to halt the aggression, in the fall of 2021, the Azerbaijani government openly announced that it would begin to destroy the Armenian cultural heritage of Artsakh and to erase traces of the Armenian language from monuments. The European Parliament is one of the first institutions that has reacted to this Armenophobic policy. On March 9, 2022, the European Parliament adopted an urgent resolution by an overwhelming majority (635 in favor, 2 against, 42 abstentions) on “The destruction of cultural heritage in Nagorno-Karabakh”.

The trigger for the resolution was the announcement by Azerbaijani authorities that they will set up a working group that will erase Armenian inscriptions from the religious monuments of Artsakh which have come under the control of Azerbaijan since the 2020 Artsakh War.

In the past, European institutions have been hesitant to speak out against the Armenophobic policies of Azerbaijan. They focused on a false equivalence, failing to identify which side was instigating ceasefire violations. Knowing full well that Azerbaijan had begun the 2020 Artsakh War and that Turkey was masterminding the attack and supporting it through delivering drones, recruiting mercenaries and stationing its air force, European institutions had largely remained silent about these markers of Azerbaijan’s aggression.

The recent EP resolution clearly mentions Azerbaijan’s destruction of Armenian cultural heritage in Artsakh, however. It enumerates the attacks against numerous religious sites, such as the Holy Savior Ghazanchetsots Cathedral in Shushi, as well as Zoravor Surb Astvatsatsin Church near the town of Mekhakavan and St. Yeghishe in Mataghis village during the 2020 Artsakh War. It also covers the period before the recent war, referring to the destruction of 89 Armenian churches, 20,000 graves and more than 5,000 cross-stones in Nakhichevan. Previously, the cultural genocide of Nakhichevan’s Armenian heritage had not been brought up often by Western figures, setting a precedent for continued destruction.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) had issued provisional measures on December 7, 2021, as Armenia had filed suit against Azerbaijan for violating the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racism (CERD). It specifically called on Azerbaijan “to take all necessary measures to prevent and punish acts of vandalism and desecration affecting Armenian cultural heritage, including but not limited to churches and other places of worship, monuments, landmarks, cemeteries and artifacts.” The decisions of the top court of the United Nations are binding in their essence; however, Azerbaijan has not complied with the Court’s orders.

The EP resolution also slams Azerbaijan’s Albanification of Armenian churches, used to justify their appropriation. It reads, “The elimination of the traces of Armenian cultural heritage in the Nagorno- Karabakh region is being achieved not only by damaging and destroying it but also through the falsification of history and attempts to present it as so-called Caucasian Albanian; whereas on 3 February 2022, the Minister of Culture of Azerbaijan, Anar Karimov, announced the establishment of a working group responsible for removing ‘the fictitious traces written by Armenians on Albanian religious temples’.”

The Caucasian Albanian theory was started by Ziya Buniyatov, who tried to argue that Armenians were not the indigenous people of Nagorno-Karabakh and had only arrived after the tsarist Russian conquest of the territory from the Persian Empire. The Caucasian Albanians (Aghvan, in Armenian) are not related to the modern-day country of Albania in the Balkans. They ruled over a kingdom during the classical period that lay northeast of the Kur River, bordering but not including the Armenian provinces of Artsakh and Utik. Later, these two provinces were included together with Caucasian Albania in the territorial administration of the Persian Empire. The Christianization of Caucasian Albania was closely tied to the Armenian Apostolic Church and ultimately came under its jurisdiction in 705 AD. However, Buniyatov propagated a false theory that Armenian inscriptions on churches were only added after the 1800s.

The European Parliament not only strongly condemns Azerbaijan’s continued policy of erasing and denying Armenian cultural heritage in and around Nagorno-Karabakh but also asserts that “The erasure of the Armenian cultural heritage is part of a wider pattern of a systematic, state-level policy of Armenophobia, historical revisionism and hatred towards Armenians promoted by the Azerbaijani authorities, including dehumanization, the glorification of violence and territorial claims against the Republic of Armenia which threaten peace and security in the South Caucasus.”

This marks the first use of the term “Armenophobia” in official European documents as a state policy of Azerbaijan. Hatred against Armenians that have led to a succession of pogroms against Artsakh’s population is the primary reason that Artsakh cannot accept ever returning to Azerbaijani jurisdiction. These tendencies have only worsened since the 2016 Four Day April War and throughout 2021. A report by Artsakh’s Human Rights Ombudsman’s office details how “extreme Armenophobia has become normalized in an increasingly authoritarian Azerbaijan. It is perhaps no coincidence that this disturbing rise in Armenophobia has gone hand in hand with systematic repressions on much of Azerbaijan’s budding independent civil society.”

The document goes on to present examples of Armenophobia among Azerbaijani state officials and public figures, and how they are violations in the context of international law. While international mediation focused on “preparing populations for peace”, “Azerbaijani state officials at the highest level have frequently been involved in fuelling anti-Armenian xenophobia and hatred, glorifying murderers of Armenians, and contributing to the increase of the divide between the two nations.”

The European Parliament called on Azerbaijan to allow unhindered access to UNESCO’s independent expert mission to the heritage sites in the territories under Azerbaijani control, and to ensure that no additional destruction of Armenian heritage sites occurs prior to their arrival. The European Parliament also encouraged the use of the EU Satellite Centre (SatCen) to provide satellite images in order to help determine the external condition of the endangered heritage in the region.

During the recent visit of Artsakh Foreign Affairs Minister Davit Babayan to Brussels in February 2022, the cross-party Friendship Group with Artsakh was relaunched in the European Parliament, which includes MEPs across the political spectrum. Of course, such initiatives are very encouraging and enrich the Armenian diplomatic arsenal. Ultimately, however, it is up to European institutions to put words into actions.

New on EVN Report

Women, Paper and Power in the Medieval Period

A historical retrospective of the social realities and perceptions of the legal status of women in the Middle Ages, specifically in the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia.

Read more2022: The Year of the Armenian Diaspora

2022 was proclaimed the Year of the Armenian Diaspora by Aram I, the Catholicos of the Great House of Cilicia. Tigran Yegavian writes that while this may be an opportunity for candid self-reflection, certain points need to be explored further.

Read moreIl Risorgimento Italiano and the Armenian National Movement

In trying to understand what nationalism is or if it can be strictly national, this article re-examines the Armenian national movement of the 19th century in relation to the Italian Risorgimento.

Read moreThe Montreux Convention and the Turkish Gateway to the Black Sea

Given the strategic significance of the Bosphorus and Dardanelles, the power to implement the Montreux Convention underscores the strategic importance that Turkey retains due to its geography.

Read more