The United Nations was conceived in the final days of World War II with one main mission: to maintain international peace and security, by preventing conflict between its member states and promoting international cooperation.

The Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I), signed between the United States and USSR in 1991, similarly tried to improve global security by committing the two countries to reduce their nuclear weapons stockpiles. Under this treaty, the two sides were required to communicate exact quantities of their nuclear weapons. In 2020, the worldwide nuclear weapon inventory is estimated roughly at 13,410 warheads.

Context and Inception

Who could imagine that there would be a need to carry out a strategic inventory of (information) technologies? In 1998, Russia addressed a letter to the UN Secretary-General, expressing concern about the potential for “emergence of a fundamentally new area of international confrontation,” that could lead to instability and unintended escalation, posing a risk to international peace and security. Russia was referring to the development of “information weapons, the destructive ‘effect’ of which may be comparable to that of weapons of mass destruction.” Attached to this letter, a draft resolution highlighted that “optimum inventory” of information technologies would be possible “in the context of broad international cooperation” and called for a process to examine developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security.

Russia’s tabled resolution has been open for sponsorship since 2006. Armenia was one of the first countries, along with Belarus, China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Myanmar, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, to support this resolution on an annual basis.

This article discusses the progress made in the UN toward identifying threats to international peace and security arising from the use of information and communications technologies (ICT), and introduces mechanisms offered for building an international framework for cybersecurity and stability.

UN Group of Governmental Experts (UN GGE)

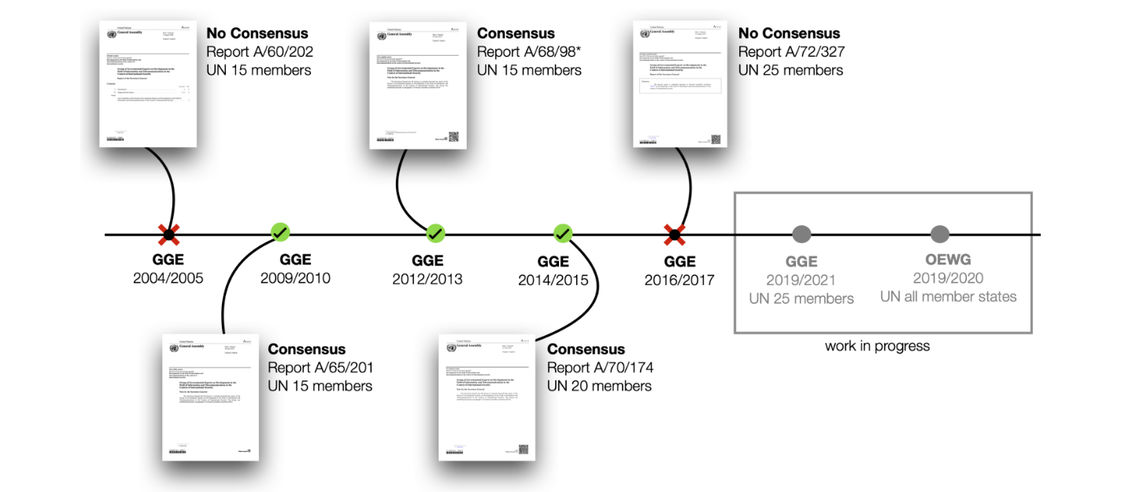

The UN Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security was formed to look into ICT developments and identify potential threats to international peace and security. The experts are selected on the basis of equitable geographical distribution. The GGE undertakes a study on the assigned topics and reports the outcomes, as well as recommendations, which are consensus-based, to the UN General Assembly. The GGE has convened for five sessions since its inception. Currently, the GGE is undergoing its 6th session, and will present its final report to the General Assembly in 2021. Essentially, the Group was formed to offer mechanisms for solving cyber conflict among states.

There are further questions to be asked about the effectiveness of the UN framework to solve cyber conflict. Firstly, how does cyber fit into the international peace and security context? Among the Security Council’s determination of what constitutes threat to international peace and security, such examples would be the situation in Libya (2010-2011) with regards to the violence and use of force against civilians (see resolution) and the use of chemical weapons in the context of the civil war, referring to the case in Syria (2012-2013) (see resolution). So far, the Security Council has not convened a formal meeting dedicated purely to the use of ICTs and/or cyber operations as a standalone issue. Is this an indication that disrupting online services, damaging industrial control systems or defacing websites are not matters of international peace and security?

Secondly, is the UN First Committee the optimal venue to discuss the use of ICTs, or more precisely, constraining the misuse of ICTs? Due to the Committee’s context and mandate, it shaped and continues to feed this dialogue of “cyber” among states with a politico-military rationale. It is clear that accelerating ICT maturity and innovation was threatening for some states when the first call was made in 1998. Over twenty years, however, the interests and the motivations of (some) states have changed, and there may now be no genuine appetite for a solution.

Thirdly, even where the GGE/OEWG offered recommendations, they are not binding. Moreover, it is difficult to envision the implementation of these recommendations among adversaries.

By analyzing these recommendations and the dynamic in general at the UN, it is to be concluded that states should help themselves. States should protect their infrastructure, assets, society and build resilience in all aspects – technical and non-technical.

For Armenia, these observations highlight several policy actions:

- First, domestically define what the optimal level of digital dependency would be for which particular services. What is the digital posture and model that Armenia wishes to develop and how can ICTs support or perhaps undermine Armenia’s strategic goals and objectives?

- Further, implement a coordinated and defense-in-depth strategy that would entail increasing the security of digitalized (critical) infrastructure and essential services by rigorously imposing and supporting the implementation of security measures countrywide.

- To ensure broad preparedness and prevention against cyber-attacks and their effects, continuously educate the local population on cyber risks and the implications of malicious cyber activities.

- Determine which international processes would help achieve Armenia’s strategic goals and devise clear input for relevant international discussions. For instance, this can be achieved through state responses at UN processes.

Acknowledgements: The author expresses her gratitude to Eneken Tikk and Mika Kerttunen of the Cyber Policy Institute for their guidance on UN processes.