Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

Thus, love of a country

Begins as attachment to our own field of action

And comes to find that action of little importance

Though never indifferent. History may be servitude,

History may be freedom. See, now they vanish,

The faces and places, with the self which, as it could, loved them,

To become renewed, transfigured, in another pattern… for history is a pattern

Of timeless moments.

– T.S. Eliot[1]

The end of the 2020 Artsakh War, which resulted in a defeat for the Armenian side, led to, among other things, a natural rise in nationalism among the populace and Armenians in the diaspora. It is natural, because nationalism accompanies almost every armed struggle and its immediate aftermath. However, in the case of Armenia, after the defeat, an opinion that was widely circulating in social media was that the war was lost due to the individuals making up the government not being nationalist enough or the populace abandoning the principles of nationalism. The main argument is that the post-2018 revolutionary culture is no longer national but international. While the statement is not true, it still raises a question about nationalism and its origins. What is nationalism? Can nationalism be strictly national?

The first of these questions supposes a definition of a concept that has been in circulation since the end of the 18th century. A concept as amorphous as nationalism, with its many variations such as cultural nationalism and political nationalism, can never be defined clearly in an all-encompassing way. However, it can be contextualized in order to become more tangible and comprehensive. Nationalism in the 19th century, at least in the Armenian experience, was first and foremost a liberation movement aimed at freeing Western Armenia from the oppression of the Ottoman Empire. As such, it allowed for a rather interesting connection between the lot of the Armenians and other nations that were under foreign rule. That the efforts of the Armenians in Eastern Armenia were also predominantly aimed toward the liberation of Armenians from Ottoman oppression is evidenced by the fact that there were no active plans to rise up against Russian rule. Disagreements between the Russian government and the Armenian governorate were resolved within the framework of the empire itself. Occasional revolts, such as the participation of Armenians in the Revolution of 1905, were aimed at reforming the system of governance within the empire, not to throw off its yoke.[2] However, the national liberation movement was accompanied by cultural nationalism both in the eastern and western halves of Armenia. Even though this article will not focus on the latter, it will be referenced occasionally for a better understanding of the role of nationalism in Armenian history.

Reinhart Koselleck once wrote that history is better understood by the defeated rather than the victors, because the former ask about the causes of their defeat. Nothing could be more dangerous in Armenia’s situation than coming up with causes that have no bearing on reality.[3] If we want to arrive at workable solutions, we need to put to bed the discussion about how a lack of nationalism led us to where we are today. Perhaps a step in this direction would be to re-examine the Armenian national movement of the 19th century in relation to the Italian Risorgimento (Resurgence), to show how international nationalism conceptualizes war, nationalism and defeat.

Similarities Between the Italian and Armenian National Movements

National movements do not only imply political action, wars or revolutions. At times, they touch deeper tropes in a people’s history: dreams, ideas or hopes that have survived, perhaps for centuries, and shape the way a group of people acts. Hence, it is important to underline a dream developed by both Italians and Armenians independently that hints at an early form of national desire for independence. The word nationalism here is used with a certain reservation, simply for want of a better word. In the Armenian context, it was the dream of Nerses the Great, the Armenian Catholicos from 353-373 AD, that a savior from outside would liberate Armenia and reinstate peace in its affairs. Being deprived of statehood in 428 AD, and later after the fall of the Bagratids (1045) and the Kingdom of Cilicia (1375), Armenia waited for outside help to reach liberation. This is well demonstrated in the case of Israel Ori, who made it his calling to reify the dream of Nerses the Great. In Italy, on the other hand, partly due to Dante’s vision and influence, and partly to the political turmoil in the peninsula, there was a wish for a liberator to come from the North and bring peace and freedom to Italy, a myth that played an important part in the way Italians perceived the invasion of Charles VIII in the 15th century.[4] Dante hoped for the Holy Roman Emperor to bring peace and order. Centuries later, Savonarola, an influential if divisive figure in 15th-century Florence, preached about a savior from the North.[5] These circumstances were caused by the social and political upheavals in which the peninsula, and particularly Florence, found itself. It paralleled Armenia, when the fall of the Bagratids and the destruction of the nakharar system left a gaping void in the social hierarchy of the populace. But these dreams are only early forms of patriotic or national sentiments, which at least in the case of Italy had little influence on the actual 19th century national movement.

In the course of Italian history, this dream lost its symbolic meaning. If Italy became politically independent, it was mainly due to its own internal effort, aided by the sympathy of foreign observers.[6] Here Giuseppe Garibaldi plays an important role; his persona alone carried enough weight to attract a transatlantic interest into the affairs of the Italian Risorgimento. A notable example is Andrea Aguyar, a freed slave from Uruguay, who took part in the initial struggles for Italian independence after the 1848/1849 revolutions and died in battle defending the Roman Republic (1849). The Italian Risorgimento, since its inception, has been a worldwide phenomenon.[7]

Armenians, on the other hand, due to the complete loss of statehood, were forced to cherish dreams of liberation through the help of an outsider. Russia ultimately took this role upon itself. Consequently, the current Armenian Republic, due to its peculiar development as a state within the Soviet Union and before that as a governorate within the Russian Empire, still struggles with a Russian complex. However, the western half of Armenia, which lived under the Ottoman yoke until the 1915 genocide, followed a somewhat different path. Its struggle against the Ottoman Empire covered almost the entirety of the 19th century and was a matter of international attention.

Leaders of Armenian political parties, pursuing nationalist sentiments, found themselves in exile, similar to a number of leading Italian nationalist thinkers. For example, Mazzini founded Young Italy (La Giovine Italia) while in exile in Marseille in 1831 and, through clandestine connections, initiated a number of failed revolts in the peninsula. Eventually, Mazzini managed to bring about the short-lived Roman Republic, which was subdued with the help of the French Army called upon by Pope Pius IX.

The Armenian political parties had their headquarters in Geneva (Hunchakian Party), Marseille (Armenakan Party led by Mekertich Portukalian), and Tbilisi (Armenian Revolutionary Federation). This presence in the west and the Russian Empire ensured that the struggle for the liberation of Western Armenia was heard internationally. Moreover, Armenian political parties employed various methods of organizing the local Armenian population and encouraging them to rebel, e.g. implementing the ideology of the Narodnik movement taken from the Russian Empire. Through a series of popular revolts, attempts were made to force the Ottoman government into improving the conditions of the Armenians. A type of 19th century nationalism hence took on an international character, in that it was depicted as a struggle of the oppressed against an unjust rule.

Another feature that links the Armenian and Italian national movements is their association with heroes. The name of Giuseppe Garibaldi still finds positive reception in modern day Italy, whereas some of the other official “heroes” of the unification, such as the first King Vittorio Emmanuelle II, have a far more ambiguous and less favorable reputation among the public.

In fin de siècle Armenia, the national liberation movement was being driven forward by an independently organized militia, fedayi, stories about whom still have a mythical value in the Third Republic. Andranik Ozanian, Kevork Chavush or the most polarizing figure of them all, Garegin Nzhdeh, are but a few of the fedayi that played a similar role to Garibaldi in Armenian history. Given that the Armenian public was constantly informed about Garibaldi and his efforts at unifying the entire Italian peninsula (and it should be noted that the reports about him and his deeds were predominantly, if not always, in a positive light), it shouldn’t be surprising that this mystification of his figure played an important role in the way the Armenian fedayis styled themselves.[8] Or could this be just another pattern of history revealing itself in different contexts? One thing is certain: the Armenian and the Italian national movements were far more popular and less centralized in their efforts, in the sense that there was an attempt to mobilize parts of the ordinary population because there was a lacking support of, or in the case of Armenia a complete absence of, a professional army.[9]

Struggle of the Oppressed for Freedom

The similarities underlined in the first part do not end there. There was also a great sympathy between the two “oppressed” people, who were under foreign rule.[10] Mikayel Nalbandian is the most famous example of an Armenian observer of the events of the Italian national movement. While staying at Messina in 1860, he noted that it was a joyful sight to see the Redshirts of Garibaldi and the ordinary people celebrating the freedom of their fatherland by chanting the name of Garibaldi. He also notes that the bourgeoisie, or what in Italian could be termed as borghesie,[11] were chanting the name of Vittorio Emmanuel II.[12] It is not a coincidence that the lyrics of the current Armenian anthem, penned by Nalbandian, were inspired by the Italian national movement. Other notable Armenian intellectuals, such as Stephan Voskan, thought of the Italian Risorgimento as an example to follow, since Italians themselves revolted against foreign rule. Parts of northern Italy, then the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia, were under the rule of the Habsburgs. The southern part, the Kingdom of Two Sicilies, was under the rule of the descendants of the Spanish Bourbon dynasty. Voskan, inspired by the Italian national movement, thought that the Italians provided an example to follow for other oppressed nations who wanted to achieve freedom.

Later on, there were a number of Italians who showed support to the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. The son of Giuseppe Garibaldi, Ricciotti Garibaldi, wrote many letters that were addressed to the Armenian nation and were published in Western Armenian newspapers that called for an active revolt against Ottoman oppression.[13] One thing that is clear, however, is that the Italian nationalists, even after the creation of the Kingdom of Italy, continued to support the cause of the other oppressed nations, such as the Greeks and, to a lesser extent, the Armenians. The main aspect that linked Italians and Armenians was their common experience of being ruled by a foreign power. This only shows how different groups of people perceived nationalism as a way toward freedom. If freedom could be achieved by one group of people, it cannot be denied to the other, as evidenced by the active participation of Armenians in the Iranian Constitutional Revolution[14] between the years 1905-1911.[15] One could also raise the question of whether the Armenian nationalists wanted to have a national state, or if their initial goal was the unification of both parts of Armenia under Russian rule.[16] The Armenian national movement, besides fighting for the liberation of the Western Armenian territories, was preoccupied with the preservation of Armenian culture rather than its transcendence into a political entity.

Just as there were Armenian sympathizers for the Italian struggle in the mid-19th century, there were also Italian sympathizers for the Armenians at the turn of the 19th century. Nationalism was not an isolationist movement; it thrived because there was a common goal for each group. Even if the goal was to be achieved independently, each group encouraged the other in their struggle.

Irredentism and Radical Nationalism

The First Republic of Armenia was created when nationalism was nearing its zenith in the West, after the end of the First World War and as a result of the collapse of the Russian Empire. If we follow a topology advanced by Theodor Schieder, then this was the last form of creating national states, i.e. through the dismemberment of great multinational empires. The first two forms were to achieve a national state through revolution (France), and through diplomacy and national wars (Italy, Germany).[1]7 The formation of the Italian national-state, according to Schieder, came to completion only after the Great War, through the incorporation of South Tirol, which still remains part of modern-day Italy, but was absorbed only after the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. While Schieder’s topology is too rigid and too Eurocentric to reflect a correct version of history of national movements and the creation of nation states, it still holds valid for Armenia and Italy.[18] Moreover, it marks a phase in both countries’ history that shows their irredentist aspirations.

Italy ended the First World War on the winning side, even though the victory for the Kingdom was a pyrrhic one. The state was left in a situation beyond repair and the March on Rome was only four years away. Dreams of Italia irredenta were, nevertheless, still pursued by a number of radical nationalists, Gabriele D’Annunzio being one of them. He occupied the city of Fiume with a brigade of volunteers in order to make it part of the Kingdom of Italy. The imagined Italia irredenta went well beyond the borders of the Kingdom of Italy or the current Italian Republic.

Irredentism in Armenia cannot be reduced to individual names or groups, as in the case of Italy; it has a more widespread character. Every Armenian is well acquainted with the term “Armenia from sea to sea”, which refers to Armenia’s territory under the reign of Tigran the Great in the 1st century BC. The term is reflective of Armenians’ image of Armenia as an entity bigger than it currently is, a phenomenon that has been accentuated after the Armenian Genocide. The 2020 Artsakh War has further complicated the situation; the memory of the lost territories is still fresh.

In the current Republic of Italy, the ideas of Italia irredenta have been abandoned, or at least are not a dominant part of the political discourse. This is evidently not the case for Armenia, where every household might envision a different image of what the Armenian world entails. Irredentism is inherent in both national movements, but isn’t it part of all national movements? Here we deal with another pattern of history that does not show itself only in the history of one people. The beauty of history is that it cannot be confined to national boundaries. There are always spillovers, and those who want to reduce it to national history merely impede its development.

Nationalism and Its Discontents

This comparison aims to serve as a reminder that no nationalism is unique. Given a set of similar circumstances, two different groups of people can develop the same dreams and aspirations, like the myth of a savior from the outside was developed both by Italians and Armenians long before the 19th century. It is important to stress the international character of both nationalisms. Armenian parties existed in a political world of a generally European character; hence, some of their attempts at turning a people into a nation were often out of touch with the Armenian reality. Eventually, through the growth of the diaspora caused by the Genocide of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, the Armenian national movement acquired an undeniably international dimension. The international nature of the Italian Risorgimento has become abundantly clear in the preceding paragraphs. It’s worth mentioning that Italians themselves, through migration predominantly to North and South America, formed a strong diaspora, which added to the international character of Italian nationalism.

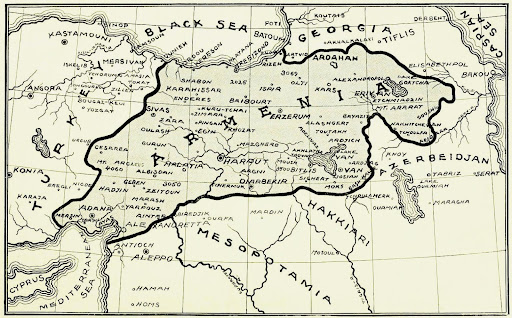

Map of United Armenia, Source: Wikimedia Commons

Map of Armenia as presented by the Armenian delegates of the Western Armenians at the Paris Peace Conference (1919). Source: Wikimedia Commons. Even the territories belonging to the Kingdom of Cilicia are included in the territory of Armenia.

Map of Italia irredenta, source: Wikimedia Commons. In green, the territories claimed by the irredentists.

It would, however, be a mistake to have a linear approach toward nationalism, i.e. to see its origin and its march through history from the perspective of linear development. Nationalism, as a phenomenon, can also have a cyclical nature.[19] It can rise and subside depending on the situation and, as such, nationalism is only a pattern of history and not a final phase. The challenge in the Armenian context is to be able to look at the national liberation movement as something that well and truly belongs to the past.

The only way to dismantle the myth of national superiority and radical nationalism is to understand the history of nationalism better, something which has not been done systematically by the historians of the Third Republic. Sadly, this task has been left to the Armenian historians in the diaspora (one recalls Ronald Grigor Suny) or to those historians who study and have an interest in Armenian history. However, to truly address the issues that nationalism causes in Armenia, there needs to be an internal discourse initiated first and foremost by historians. No outside influence is capable of actively transforming public opinion or steering it away from falling into radicalism.

Footnotes: