This year, we are marking the 30th anniversary of the Karabakh Movement. To be fair, it should be noted that the Movement did not begin three decades ago but rather on that day in 1921 when Stalin’s regime forcibly handed over Nagorno Karabakh to the newly established Republic of Azerbaijan. Over the following 70 years, the Movement had different manifestations, there were ebbs and flows, but the fire that was unleashed was never extinguished. The 1960s in particular is significant because the wave of the movement rose once again and spread throughout the Soviet Union, making its way to the Kremlin.

The Karabakh Movement reached its peak in 1988 and transformed into a national-liberation struggle. Taking advantage of the opportunity afforded by Gorbachev’s announcement of democratic principles, the Armenians of Karabakh again voiced their ultimate wish to reunite Nagorno Karabakh with Mother Armenia. On February 12, 1988, heated meetings were taking place in the district and in the Regional Soviet (Council) of Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO); representatives from Baku were also present, they had come to convince and scare the participants of the uprising to step back from such a decision. But the wheel of history had gained momentum and no one would be able to stop it.

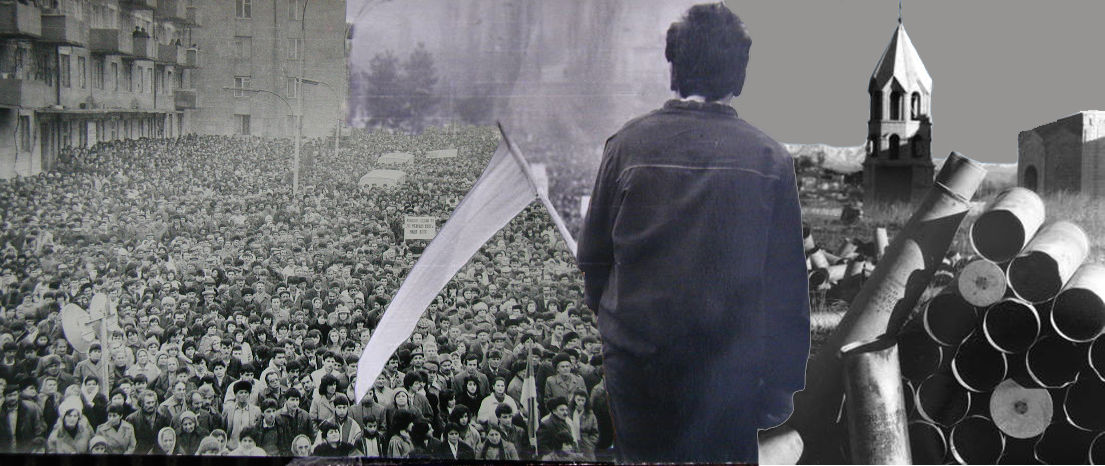

The same day, mass demonstrations took place in Askeran, Hadrut, Martuni and Martakert, the next day, on February 13, in Stepanakert. People were demanding an extraordinary session be called and the decision be made for NKAO to secede from the Azerbaijani SSR and join the Armenian SSR. And on February 20, after indescribable efforts, the historic session, which made an irrefutable decision, convened. I remember those days in awe. It was our golden age, our hour of glory. I often wonder if there will ever come a time when our souls and spirits will soar like they did then.

They tried to clip our wings just as we were taking flight. Moscow and Baku not only refuted the decision of the session, but also strongly condemned it. This, however, could no longer keep us from reaching our goal. We had killed the slave within us and our spirit had awoken from its lethargic sleep.

The Movement that started in Karabakh soon spread to Armenia, to all the countries where at least a single Armenian lived. The sea of people in the central square in Stepanakert and Opera Square in Yerevan, especially following the Sumgait Pogrom, understood that self-reliance was paramount. The prophetic words of Charents became our mantra: “O~ Armenian people, your salvation is in your collective strength.” These words guided us through a war imposed by our adversary, they still guide us today.

Even the devastatingly tragic earthquake in 1988 did not break the resolve of the nation, did not crush the concern for the fate of the Artsakh Armenians. Gorbachev’s astonishment was beyond measure during his visit to the disaster zone, when people who had just been rescued from under the rubble would ask, did anything happen in Karabakh?

The Karabakh Movement united Armenians. I’ve had the opportunity to visit Europe, the United States, to meet many Armenians who would admit to not having even heard of Nagorno Karabakh before 1988. And they would add – Karabakh opened our eyes, we began to feel fully Armenian. And it is no coincidence that during the war, not only natives of Artsakh but volunteers from Armenia and the Diaspora stood on the frontline of defense. Monte Melkonian is a name we must remember, about whom we made a movie and I wrote a book and had the honor of being his friend. What he said during our first interview, “If we lose Artsakh, we will have turned the last page of Armenian history” has become a popular saying and is relevant today. Fortunately, the nation perceived the imperative and Artsakh became a pan-Armenian issue; even the issue of the continued existence of a centuries-old nation.

As a journalist during the Karabakh Movement and the liberation war, I witnessed numerous unforgettable situations, moments of heroism and met interesting people. All of this left a permanent mark on my life. I remember the reopening ceremony of the Gandzasar Monastery on October 1, 1989 as if it were today. The sermon read by the newly appointed head of the re-established Artsakh Diocese of the Armenian Apostolic Church, Bishop Barkev Martirosyan, was more than just a sermon. I don’t think I have ever felt anything similar to that.

Or on May 6, 1992, when the troops were preparing to liberate Shushi, the Bishop said, “Here, in Artsakh, the fate, the present and future of the Armenian people is being forged. This is where our victorious odyssey begins, even if it must commence on a military path. We stand at the threshold of victories. This is what will change our fate and we will find the right path because we are becoming one with God. Victory is ours.”

These words were recorded as was the holy liturgy at the Ghazanchetsots Church after the liberation of the fortress city, imagery that even when viewed a quarter of a century later, makes it impossible to suppress tears. Is the person who has witnessed this, is the generation that liberated the homeland not blessed? True, we paid the price in blood, in great suffering and hardship, but were rewarded with freedom.

And then there was the resistance of Karintak, a village that was under siege for about four years, yet no one deserted their birthplace. When a grandfather came from Stepanakert to take his 10-12 year old grandchild to the city, the child said, “But if I leave, who will protect my home?”

When on January 16, 1992, an Azerbaijani army unit 200 soldiers-strong and under the command of their defense minister attacked Karintak to wipe the village off the face of the earth, 16-year-old Narine Arakelyan was supplying bread and ammunition to her father, brothers and the other defenders of her village. And while she was helping transport the children to a relatively safer place (as if she was not a child herself) the adversary’s bullet hit the brave girl.

People came to the aid of Karintak that day from neighboring villages, from the capital Stepanakert. Together with the residents of the village they protected the ancient settlement nestled under the foothills of the cliffs of Shushi and forced the retreat of the adversary causing human losses. Regrettably, we too had losses, one was Grisha Mikaelyan from Sznek, a student of mine; I had taught him Armenian language and literature in 1984 when he was in the seventh grade.

They brought his body to Stepanakert and were going to take him back to his native village the following day. Grishik’s father, Ashot Mikaelyan, a teacher, swallowing his bitter tears, addressed those gathered, “People, I’m not mourning because my son died for the freedom of Artsakh. You too should not be crying, be proud to have such sons.”

Try to bring this nation to its knees. You can’t. You have tried, you failed. Resort to your foolhardy ways, but let it be on your conscience.

After the war, a foreign correspondent asked me, “How is it that you were able to win this unequal war?” I brought the example of Karintak and he replied, “All is clear for me now.”

It is hardly possible to relay all that I have seen and lived through in those years. I try to do that through films and books.

The anniversary of the Karabakh Movement is naturally an occasion to remember, contemplate, and reevaluate everything that happened. One could insist that it would have been better if we had done things differently. Possibly. But we have what we have – one nation, two republics – one of which is the Republic of Artsakh even if not yet officially recognized by the international community and even if the Karabakh conundrum has not been officially solved yet, we solved it for ourselves a long time ago. Azerbaijan does not want to come to terms with this and cherishes false hopes that someone would again serve Karabakh to them on a platter. As Leonid Azgaldyan said, “This is Armenia, the end.”

EVN Report wishes to thank the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES) for their cooperation and support.