This article is not dedicated to the Karabakh Movement. More than anything, it is dedicated to the versatility of reality, or something along those lines.

If I had listened to my interlocutor in February 1988, the conversation would have ended badly because we were on opposite sides of the “barricades” and the young participant in the movement, who was enjoying every minute of the Soviet Union collapsing, would not have tolerated the part of the story about how the Soviet system was listening in on us and in an official capacity trying to impede our movement.

My interlocutor is now a businessman, previously and including during 1988-89, he was an official of the political committee (kaghkom) of the local Communist party of Yerevan. He was telling me the story of our movement from the opposite side. From the first days of the movement they were with us in the Square, listening, taking notes about who said what, how people reacted, what they were planning for the next day and would then report what they had heard to the political committee.

He is a humorous person, and talks ironically about their plight and our naivety.

It is easy to listen to it now, but when I imagine for one minute that if I had heard this in 1988…I’m surprised how differently reality can be perceived today as opposed to thirty years ago. Perhaps I would not have been able to hear it even today had we not become the witnesses to even worse things after 88.

In 1988, while the Opera and any other building or structure that was associated with our movement had taken on the status of a holy site, for those on the other side, the perception of the reality was much more practical. What my interlocutor was saying now seemed amusing to me as well. He said the movement’s conditional ‘premises’ were the grounds of the Opera, the Writer’s Union, the Komsomol,* the Hall of Conferences, the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the National Academy of Sciences. Some of these buildings fell under the police jurisdiction of the 26 Commissars, the other, Miasnikyan, the Opera was part of the Spandaryan jurisdiction…and the police chiefs of these three districts were very motivated to see the rallies, marches and demonstrations move from theirs into one other jurisdiction. Miasnikyan was just a little up from the Opera, a bit further down was Spandaryan. And when the rally would move from one jurisdiction to the next, the police department would breathe a sigh of relief that the rally had moved on, and would gleefully inform the other jurisdiction.

The police were strictly ordered not to use any force against the operations of the movement; they simply had to prevent any small violation or hooliganism.

The former Soviet official proudly said that in the midst of such a powerful movement, there was only one victim, Khachik Zakaryan, whose death shook not only the protesters but the authorities. He said that the person who shot Khachik did not do it on purpose, he was a soldier in the Soviet army, a junior lieutenant.

Hearing about their ingenuity and resourcefulness, and ours, from a different perspective was interesting, but even 30 years later, it was hard for me to hear that during the days of those powerful demonstrations they had infiltrated our ranks as participants, to express and spread their so-called disappointment in the movement: “Today, they’re not going to say anything interest, it’s better for us all to go home.” And with this tactic trying to dilute the ranks of the massive rallies. To be honest, at that moment something snapped in me, perhaps this was the most unpleasant thing to hear.

My interlocutor’s humor, at any rate, saved the situation and yet at times it was not clear whether it was his humor, the passing of time or that he was saying wise things and also making fun of their side.

Looking at the movement from their side, we sometimes were powerful in my eyes, sometimes naive, sometimes even ridiculous. But the way our conversation began pleased me. He said, “Do you know when we (Soviet officials) understood that there was nothing we could do and that we had lost? When in one day in February 1988, the rally had stretched from the Opera to the “Rassia” movie theatre…we were stunned at what was taking place and we finally understood everything when the members of the Karabakh Committee delivered their speeches from the platform in Lenin Square.”

In fact, what we had felt coincided; we also felt our victory on that day and then later (more precisely ) , their defeat. Because for our entire conscious life during the November 7 and May 1 parades, when we would march through Lenin Square, they would make us stand at attention, they would pull and fix our celebratory red dresses, they would threaten us that if something wasn’t just right, we would receive a reprimand, be sent home from school, and a disciplinary note would also be delivered to the institution where our parents worked…And when we would walk by the platform, we would shiver regardless of the temperature. But when Demirjyan would wave to us smiling, it felt as though he was greeting each of us personally and could see of each and every single one of us. And that day in 1988 on November 7, when we came up to the platform and heard the voices of the leaders of our movement, it was another kind of joy, and now, aside from the Opera, the party’s unattainable platform was also ours. At that moment, we, the people understood that we had won and now I realized that the authorities of the day also knew that.

Laughing, my interlocutor said that when Vano Siredeghyan in his speech said… “Among our ranks are a group of informants in ties and suits, please be careful to avoid provocations” the following day, all the party informants had taken off their ties when they came to the square.

Humor was easing the rough edges of our conversation. The former official of the party’s political committee of Yerevan said, “One day when I was returning from the Square to the office my superior asked, ‘What did they say today?’ My nerves were already frayed, and I said, shef jan, they have been saying the same thing for four months, ‘We want Karabakh…’ what else do they have to say?” Speaking about himself and others like him back then, he said, “Our knowledge, our organizational skills could have been utilized by those who came after us, but they turned us into enemies; we weren’t fundamentally opposed to the demands of the Movement, we were simply doing our job with inertia and they weren’t specifically ordering us to take action against the rallies, there was no point, but they should have taken advantage of what we knew, of our experience.” He is sure that they lost and that the Soviet Empire collapsed because they lied incessantly. He said, “We would go to meetings, and lie, at the conferences, we would lie and then we would leave and look at each other, we knew that we were all lying and lying had become our job.”

“But you were a strange lot too,” he says. “I went to the party office one day during the beginning of the rallies and reported that some actor was addressing and leading the rally. My superior asked which actor and I said I don’t know, he has played only one role in his life in Tsori Miro, the role of a Turk.” He was referring to Vache Marukhanyan.

“Certainly it wasn’t only the funny moments, there were instances when we had the same emotions as you had,” he said. “One was on November 8, the other was when the demonstration moved from Arshakunyants Street to the Komitas Pantheon, it was a torchlight rally, and everyone loudly vowed, ‘Our struggle will be victorious.’” He said that a tremor passed through all of them at that moment.

When the rally moved from the Komitas park, which was in the Orjonikikze district, into the Lenin district, the secretary of Orjonikikze reported to the secretary of the Lenin district that he had completed his task, and that now, the rally passing by Yerevan lake had reached the Mashtots district. The First Secretary of the Lenin district reported to the First Secretary of the Mashtots district, “I am handing over the rally to you, Mamikonich.” (Referring to Artashes Mamikon Geghamyan)

The political elite of Armenian SSR had tense days with the visit of members of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Anatoli Lukyanov and Vladimir Dolgikh. People had assembled on Baghramyan Avenue, near the Central Committee and the National Academy of Sciences. We were chanting and demanding that Lukyanov and Dolgikh come out and speak in front of the people. About that day my interlocutor said, “During the meeting with the political elite, tough questions were asked, this was no longer the previous auditorium, everyone was tense, the tension outside was affecting the leadership.” Aleksan Kirakosyan, Pavlik Safyan, Stepan Vardanyan, Hrachik Simonyan, Lendrush Khurshudyan and others were particularly active. Lukyanov began to speak, while questions kept being asked from the hall, saying that he wanted to start his speech by saying that he had not come to ‘place a soft pillow under our heads,’ however the questions from the audience prevented him from continuing.

Then, exhibiting the high art of a cunning Soviet official, he began talking about our brilliant poet Charents, and addressing the audience said that he would prove that he is not an enemy of the Armenian people and that he was here with sincere motives and stated that not a single Armenian had a recording of our great poet but that he had a recording of Yeghishe Charents’ speech from the first writer’s congress of the USSR in 1934. Dolgikh was silent. As my interlocutor verified, the rebellion inside the hall was suddenly quelled. Soviet officials knew not only harsh but also cunning ways of silencing the brotherly republics.

Many incidents from those days were recalled – I from our side and the Soviet official from the other. He jokingly asked, “Why did you carry that stonecross on foot on the first anniversary of Sumgait from the university to Tsitsernakaberd? Why didn’t you use a car…ay dzer tsavy tanim…”

“We took it by foot?” I asked. “Perhaps we were paying our respects to the victims…what other reason could there be?”

And he recalled how the Second Secretary of the Komsomol Ayda Topuzyan called and ordered him to halt the stonecross march to which he responded, “Ayda Onikovna, if I stop them, they will place the stonecross on me.” I think my interlocutor makes an interesting observation; he says that orders from their superiors had nothing to do with the context of the movement but rather they simply carried out their official responsibilities to avoid criticism from any other official in a personal capacity.

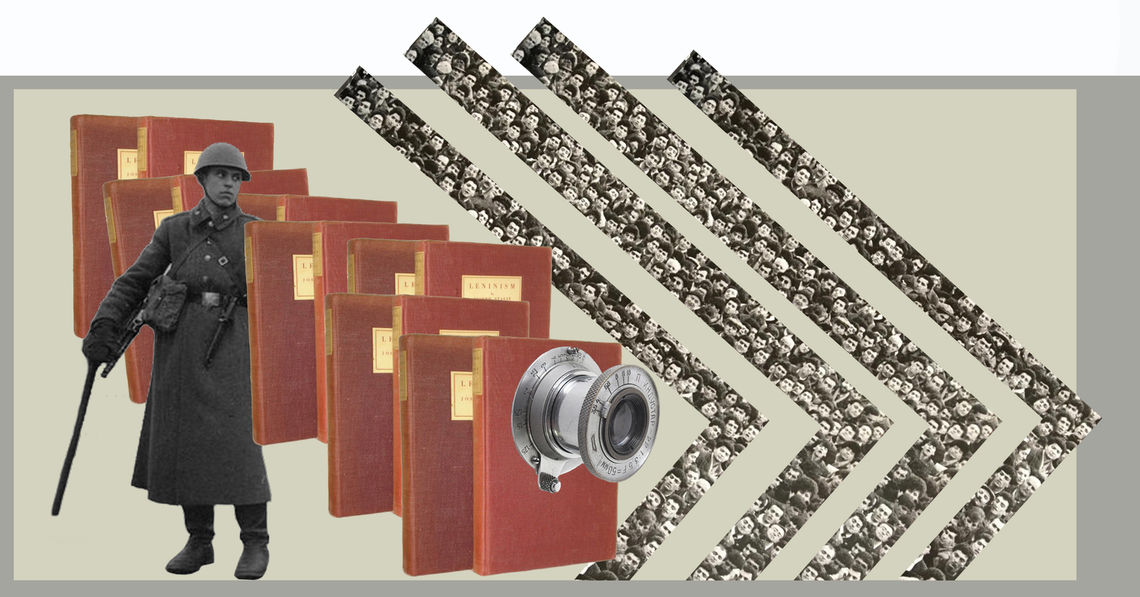

It becomes clear that they, the Soviet officials on the other side of the barricades, appreciated our, the protesters, ingenuity and humor. Russian soldiers were lined up from the Opera to the beginning of Baghramyan Avenue. The circular portion of Baghramyan was empty, from the flower shop all the way to the former bakery, drug store. The demonstrators had gathered there. And to ensure that the soldiers did not move forward, we had placed volumes of Lenin along the length of the sidewalk, beneath the feet of the soldiers to prevent them from taking a step forward. Soviet officials had also “appreciated” this ingenuity. In retrospect, the former Soviet official says that their second shock came when Levon Ter-Petrosyan became the president of the Supreme Council: “We looked at each other and said how did this happen?”

The conversation with my interlocutor was flowing because he was speaking honestly about the unusual rituals of their times, and while acknowledging the power of the movement he also noted that never once did mass violence take place in Armenia whereas in other republics there were tragic incidents. I reminded him of the events of the station and he said that no one understood what happened. And as a small and not unimportant fact he recalled the extraordinary session of the Supreme Soviet on November 24 in the Opera. Many of the deputies had not been brought gingerly to take part in the session, the atmosphere was tense.

Immediately after the extraordinary session, General Samsonov delivered a speech on television and announced that a curfew would be imposed in Yerevan. After the session, the square was surging with people, there was no room to move and the deputies still had to come out of the building. In crowded places, pushing and shoving is one of the most dangerous situations and the likelihood of a fatal outcome when trying to go against the flow of masses of people is high….and at that time through the order of the Minister of Internal Affairs, who was also inside the Opera building, another set of doors leading toward Lenin Street were opened to allow those inside the building and standing near the platform just outside to enter the building and walk out through the other side to avoid the oncoming wave of people. Our negative attitude toward the Soviet Union in those days didn’t allow us to appreciate any good gesture, even a small measure of good. My interlocutor periodically noted that the biggest mistake of the new leaders was not taking advantage of the Soviet cadres. “We were excluded from life. They were avoiding us as disgraced Soviet chinovniks (civil servants) but later, compared to others, we were saints…”

This conversation had painful depths and subtexts but once in a while, funny episodes would break the heaviness. My interlocutor recalled how on November 24, 1988, he bought a long-awaited hunting rifle from the hunting store on Marx Street. His friend had called to say that they had received a new gun. Their job in those days was to show up at the kaghkom at 9 in the morning and then go to the Square. At some point during the rally, he had gone to buy himself the rifle. He had separated the barrel and the body of the rifle and split in two, placed it inside his jacket and had come to the Square. The whole day his new hunting rifle was inside his jacket. At night, when the curfew was implemented, he had to get from the Square to the kaghkom building… He said, “If the Russian soldiers had found that rifle in my jacket, I would probably find myself directly in some other place.” In fact, the official of the kaghkom would have unwillingly become one of the ‘extremists’ who carried a gun during the days of the curfew.

Today, we, all of us live in the same country. Perhaps we are still different by some virtues of our human qualities, but we complain about the same things and want the same things for our country.

And the country changed hands…

*All-Union Leninist Young Communist League

EVN Report wishes to thank the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES) for their cooperation and support.