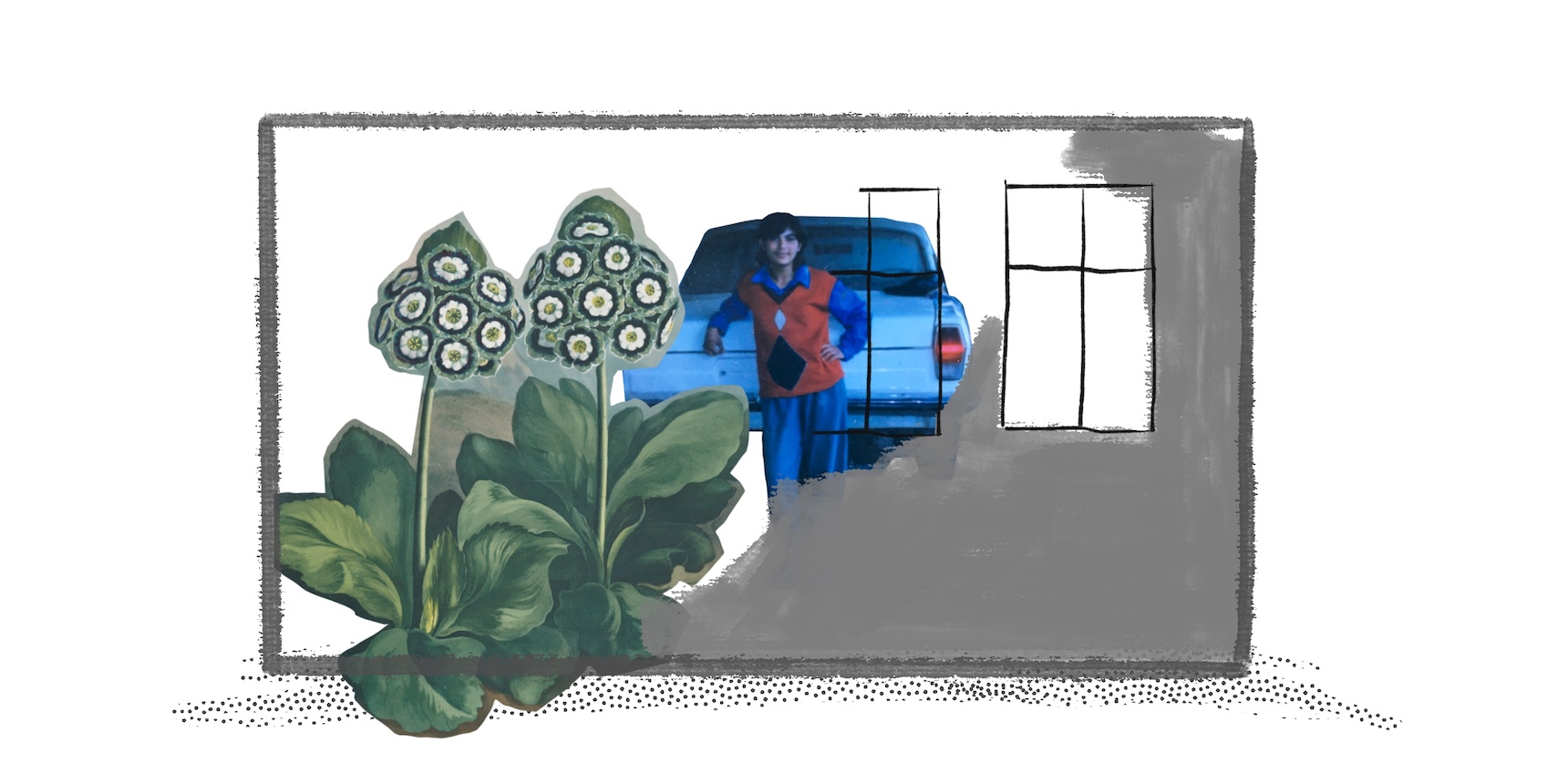

Young Hratsin and her mother, Nadya Ohanyan. Aknaghbyur, Hadrut.

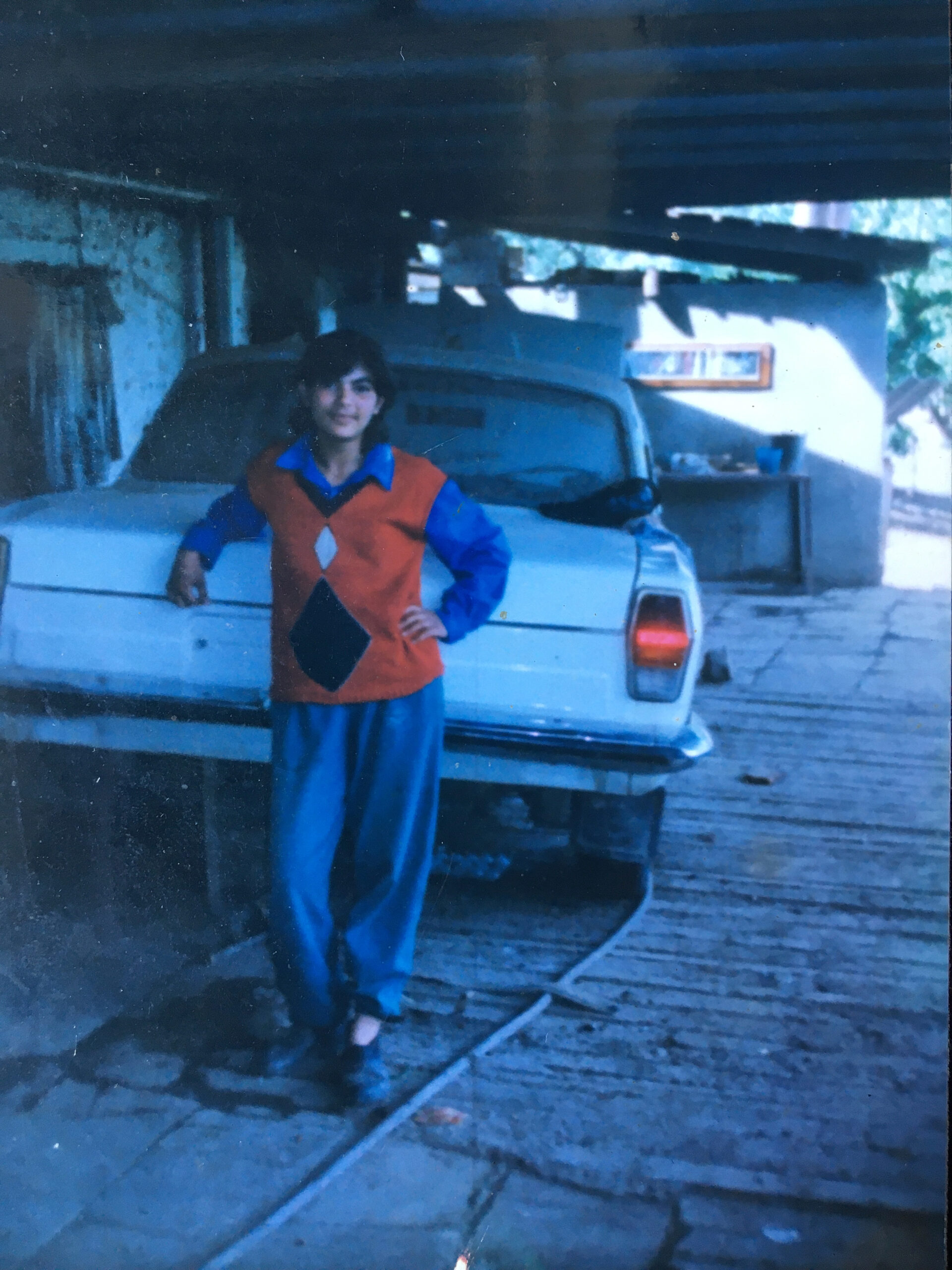

Teenage Hratsin posing in front of her father’s car in their village.

“A photo album and my dialect.”

These are the only things Hratsin Ohanyan, 38, has left of Hadrut.

Hratsin and her family are among the tens of thousands of internally displaced Armenians as a result of Azerbaijan’s 2020 invasion of Nagorno-Karabakh/Artsakh. Like many of their compatriots, after the war they decided to stay in what remained of Artsakh and start a new life in Martuni.

Born in the village of Tumi in the Hadrut region, Hratsin moved to Aknaghbyur and spent most of her adult life there. Both her and her husband’s families had lived in Hadrut for generations, and were determined to stay in their homeland as long as possible.

“On the night of September 26, we had no idea a war had broken out. On the morning of the 27th, we woke up to explosions and found the troops gathered near the village hall while the children were still asleep,” Hratsin says. The village leader of Aknaghbyur encouraged the villagers to evacuate their children, but Hratsin’s family was determined to stay. “We said we would either live or die here,” she recalls, noting there were two more families who stayed.

Hratsin’s house was at the edge of a forest which served as a shield for a while, keeping them safe from the enemy’s fire. However, as the situation grew more tense, Hratsin’s family had no choice but to leave the village. “On October 1, we celebrated my daughter’s birthday in the basement, we set up a table on gas cylinders,” Hratsin remembers. The same night, an Azerbaijani UAV hit the fir trees around Hratsin’s house cutting one in half and forcing the family to evacuate immediately the next morning.

Young Hratsin, Hadrut.

Hratsin Ohanyan with her brother and father in Khornaghbyur, Hadrut. 2004.

Hratsin showing photos in their family album, which is now the only material possession they managed to keep from their home in Aknaghbyur.

The three remaining families decided to send the children to Yerevan with their mothers to stay with one of the neighbors’ relatives. Hratsin and her four children left their home and all their belongings without a clear plan on how they would reach their destination. “I had no money on me. Nothing. I borrowed 20,000 AMD from the village leader with the condition that once it would be peaceful again and we’re back in the village, they’d deduct it from my salary,” remembers Hratsin. When they reached Stepanakert, she met a group of volunteers who offered them a ride to Yerevan: “They said we could stay at their shelter and they would provide the family with all the necessities such as food and clothes for the children until there was peace again. We had left in such a rush that my children didn’t even have socks to wear, they were barefoot.”

Considering the financial situation she was in, Hratsin chose to settle at the shelter. Later she received an offer to stay in Stepanavan with a local family where she had a little room for herself and the children. “My three kids and I would sleep on the same bed, and my elder one got the couch,” she says. While the hosts were kind to her and her family, Hratsin’s time away from home had its challenges: “I was grateful for the kindness, but I felt uncomfortable to even open the fridge and give food to my children. There were nights when they went to sleep on empty stomachs.”

For Hratsin, the gravest consequence of the war was the deterioration of her children’s mental health. She describes how at night the kids would become frightened and cry thinking there was a UAV attacking again. “They would have flashbacks from the roads or from when we were still in the village,” Hratsin says. “My elder one has been impacted most after the bombing in our yard.” Since then they have been seeing therapists both in Yerevan and Martuni. Hratsin says that Mission Artsakh [1] has been of great help, providing therapists’ assistance from Stepanakert all the way to Martuni.

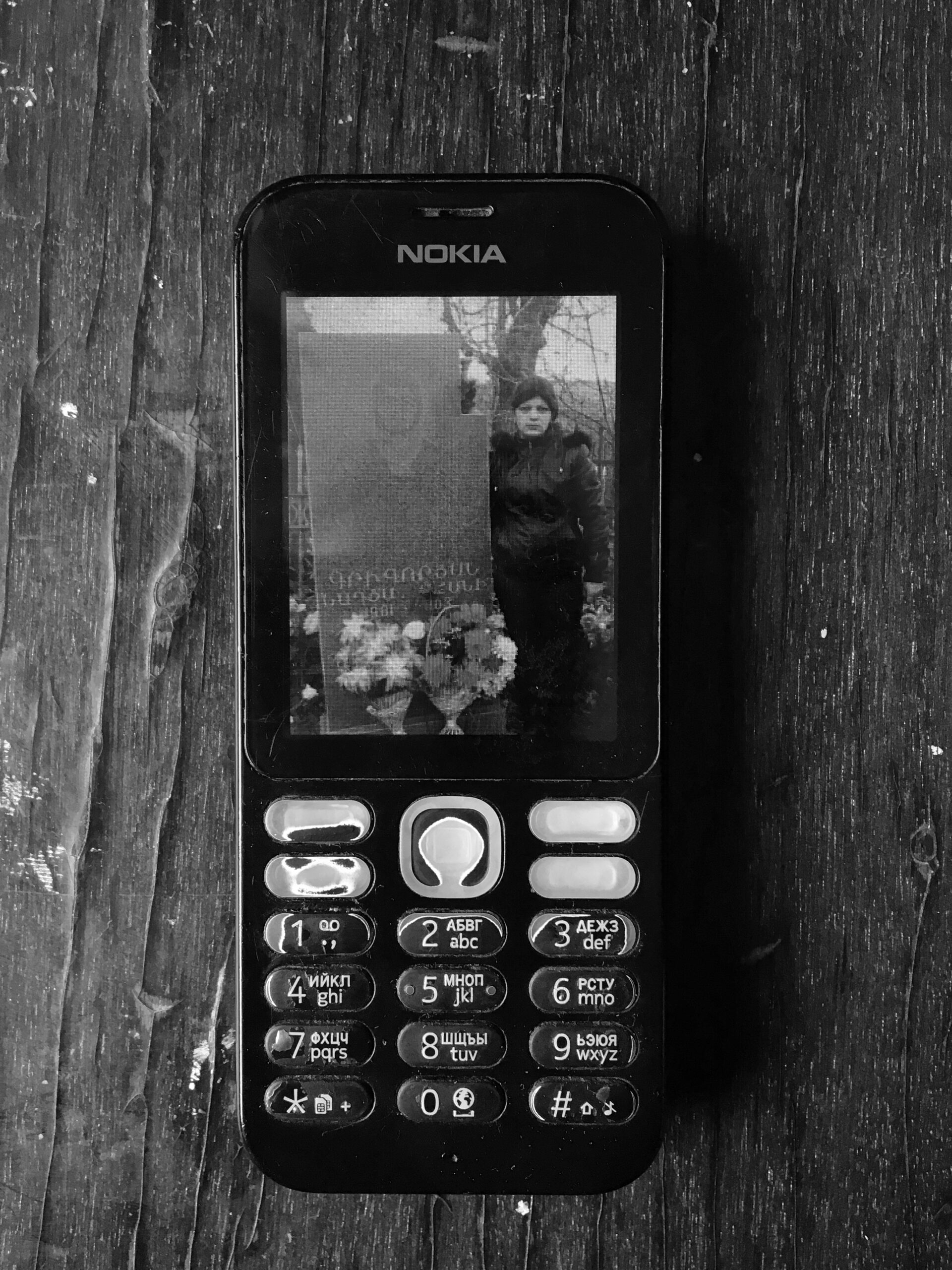

While Hratsin was navigating through the challenges of being away from home with her four underage children, her husband was on the battlefield. They were occasionally in touch and hoped they would reunite soon and return home, however, the invasion made life take a different turn. In late October 2020, Hratsin received a call from her husband Armen, saying he was evacuating the elders of their family with the rest of the remaining residents. He said that Azerbaijanis had infiltrated the village with Armenian passports and even spoke fluent Armenian. Then came the tanks and UAVs. “I was sure we would return, but now I can’t even go back to my mother’s grave,” Hratsin says disheartenedly.

A photo in Hratsin’s old Nokia phone showing her at her mother’s grave.

Trauma, Yearning and Post-War Challenges

Hratsin remembers her home with deep longing. She recalls building it from scratch with her husband:

“It belonged to my husband’s great-grandparents. When we got married, it was quite an old and small house, but later, with the help of my father, we built a new one right next to it. My father and I set the foundation with our own hands, then Armen and I built everything on top of it together, brick by brick. We turned that old house into a new, big house where the entire family – Armen’s parents, aunt, and sisters – could live with us.”

Moving to Martuni has changed Hratsin’s life considerably, creating economic and social challenges. The family is currently renting a small house that lacks proper furnishing and other essential amenities. While the rent, which was recently increased to 70,000 AMD, is paid for by the Artsakh government, Hratsin explains that there are many other expenses.”There are a lot of hardships here. Life is difficult here in every aspect,” she says. Hratsin’s displacement has deepened her family’s financial struggles. “[Back in Aknaghbyur] we grew everything in our orchard. We didn’t have to pay for anything at all.”

She attempted to recreate her orchard in Martuni, but some of the crops failed. “The quality of the soil is not the same,” says Hratsin, noting that back in Hadrut they also didn’t have to worry about irrigation since they got the water from the nearby forest. Back in Aknaghbyur, Hratsin’s family grew tsmktapan, a type of mushroom native to the region which they sold for 5000 drams a kilogram to cover living expenses. “The only thing we had to pay for was the electricity. The rest we planted and produced with our own sweat,” she says. “We used to have all sorts of produce and domestic animals, but here everything has to be bought.”

The view from Hratsin Ohanyan’s kitchen overlooking her little fruit garden. Martuni, Artsakh.

To ease the financial burden, Hratsin has taken up a job at the municipality as street sweeper. In Aknaghbyur, she used to work as a cleaner at the Village Hall. “That was my first job,” explains Hratsin. “My husband didn’t want me to get one until our fourth child was born, but due to the financial need, he eventually agreed.” After the war, the government continued providing her salary, however, the regulations don’t allow for those getting assistance from the government to have another registered source of income. Hratsin could either continue receiving the salary she used to have back in Aknaghbyur without going to work or get a new job. “You aren’t allowed to have two jobs now. So I decided I’m better off working here as it pays a little more,” Hratsin explains. Ruzanna Hovhannisyan, the head of Mission Artsakh, who has been working with displaced families says that Hratsin and her husband are among those who “never sit and wait for help.” Instead they take up whatever jobs are available.

Displacement has also affected Hratsin’s life in intangible ways. While it seems natural that families who have been relocated to the cities and towns within Armenia may need to adapt to the new environment; surprisingly, it’s also the case for many who have been internally displaced within the territory of Artsakh as well. According to Hratsin, the Hadrut region was considerably different from Martuni. She says that back in Hadrut they never experienced severe heatwaves and her children aren’t used to it. Living in Martuni she has also faced cultural differences. Hratsin and her family speak in the Hadrut dialect, which is occasionally criticized by some in Martuni. “They keep telling me, ‘Use the Martuni language.’ They want us to talk like them, but the language is all that I have left of Hadrut.”

Hratsin Ohanyan and her younger daughter Angelina in Martuni.

Growing up in Artsakh, 38-year-old Hratsin has been affected by three wars over the course of her life. The First Karabakh War took her childhood away from her, the Four-Day April War took her father from her, who’s been missing since 2016, and the 2020 Artsakh War took her home away from her. In spite of all this, she perserveres and has a resilient outlook toward the future, and is full of hope. “I don’t fear the future. I keep on living as I used to. No matter where you are, you will still keep on living. I only wish for peace so our youth won’t have to get martyred. It has been enough.”

Note: The article is based on oral history interviews with full consent by the narrator.

Footnotes: