In July 2016, Tagui Mansuryan and her parents were violently attacked with an axe by Mansuryan’s former husband Vladik Martirosyan, who killed her mother and gravely injured her and her father. Prior to the incident, Martirosyan had continually threatened the family and Mansuryan, in turn, had reached out to the police on a number of occasions. However, she was not offered the proper protection, which reflects the absence of a systematic police process for investigating cases, making appropriate referrals, and issuing protection orders, which hinges on a larger issue – the absence of legislation on domestic violence.

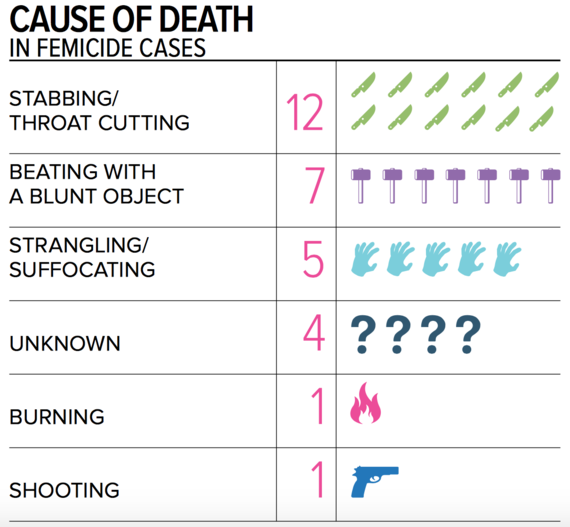

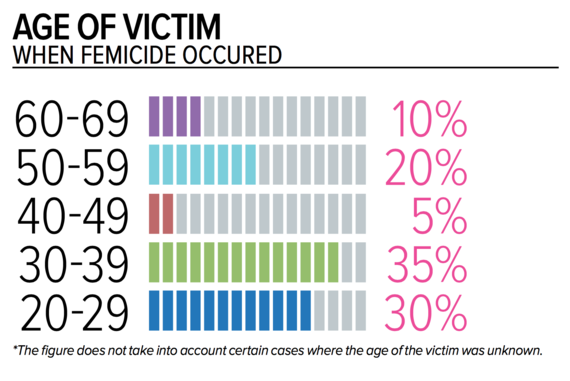

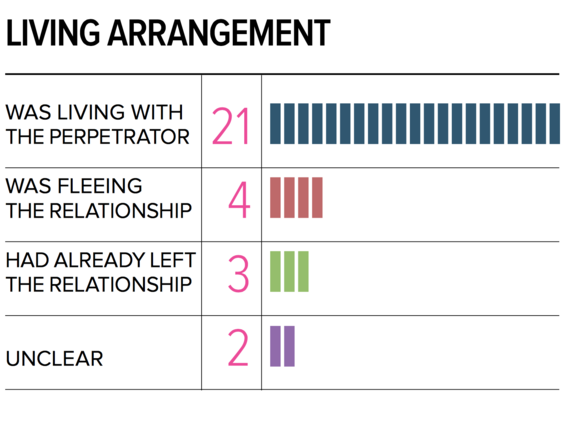

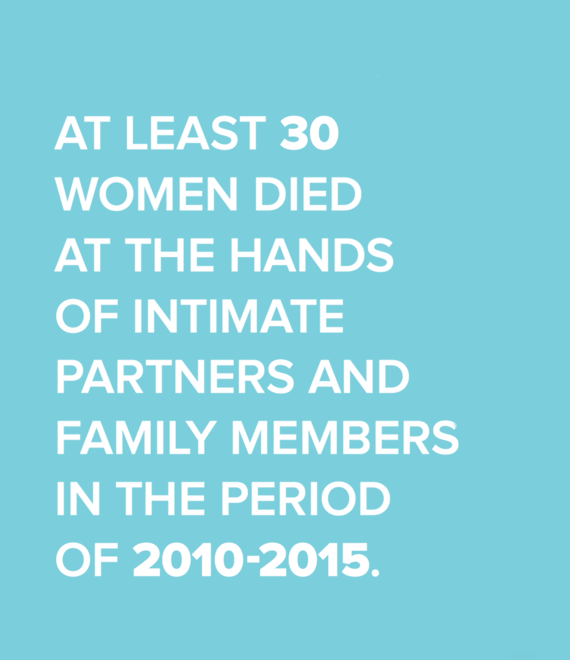

Domestic violence (DV) is a critical issue facing women globally, and women in Armenia are not immune from it. A recent nationwide survey found that nearly a quarter and half of ever-partnered women reported to have been subjected to physical and psychological violence by a male intimate partner, respectively; nearly one-fifth of ever-partnered women reported having been prohibited by an intimate partner from getting a job or earning money; and an alarming 7.6% of male respondents reported having forced a woman or girl to engage in sexual intercourse. The same survey reveals a cultural acceptance of violence against women, with over a third of respondents stating that women should tolerate violence in order to keep their families together, and nearly three quarters reporting their belief that intimate partner violence can be justified. Disturbingly, the Coalition to Stop Violence Against Women found that from 2010-2015 at least 30 women were murdered by current or former intimate partners or family members. (Ten more documented cases of femicide have occurred since 2016, though the data is not published.)

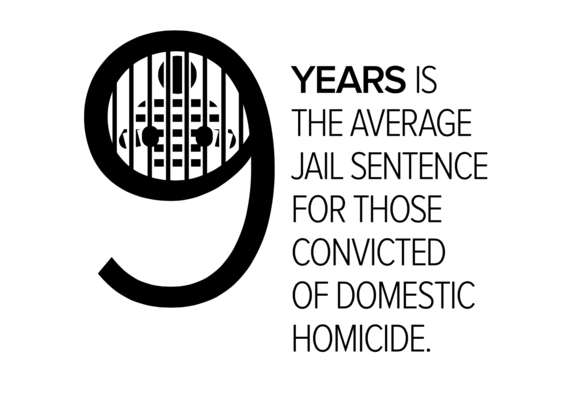

Despite certain measures that have been taken by the state to combat DV, Armenia is falling short of its international obligations, including those under the Convention to Elimination All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). There has been little political will demonstrated at the highest policy-making level and few financial resources allocated for combating DV. At present, Armenia does not have a standalone law on DV that would call special attention and treatment of such crimes. The RA Criminal Code only criminalizes assault, failing to expressly recognize domestic violence as criminal conduct. The existing criminal and administrative laws that prohibit intentional injury do not work in favor of victims, and they often withdraw their complaints when the abuser may be punished with a monetary fine that comes out of the family budget or imprisoned and unable to financially support the family.

It’s important to note as well that state programs and policies continually exclude marginalized women, including women with disabilities, ethnic and sexual minorities, rural women, elderly women, sex workers, and others, who are at greater risk of violence. Moreover, there is poor implementation of action plans put forth by the state

The lack of institutional capacity to address DV continues to be a considerable barrier for women seeking safety and protection. In 2015, there were 784 official complaints of domestic abuse to the police and over 2,000 hotline calls to the Coalition to Stop Violence Against Women alone. Given that speaking out about DV is taboo in Armenian society, it is likely that many more victims hide behind the shroud of stigma and shame or lack the ability to seek help. Specialized service providers working in the field, including social workers and medical personnel, are not trained on DV service provision, and often death threats and other warning signs are overlooked. Thus, many victims turn to the police and the criminal justice system for safety, assistance, and justice but discover that these systems fail to protect them — or worse, re-victimize them.

A handful of NGOs, including the Women’s Support Center, have worked to raise awareness on domestic violence, establish services for victims, and introduce legislation. As a result of our advocacy efforts, there is growing awareness among Armenian society about domestic violence and more women every day reaching out for support. Chronically underfunded and under-resourced, NGOs have taken on the full burden of offering services to survivors and their children, including shelter assistance. A domestic violence bill drafted by NGOs was rejected twice in 2009 and 2013. Because of top-down pressure and financial support from the EU, which made its 11 million euros in aid contingent on Armenia passing legislation, a domestic violence law is set to be passed by 2018, though concerns remain about whether it will offer the proper safeguards to victims. The draft law was recently taken out of circulation, and public hearings concerning the law have been pushed back.

Further reinforcing the aforementioned institutional problems is gender stereotyping, which trickles down from the state to the public and fosters discriminatory approaches toward women. Deep-rooted beliefs about traditional family values drive gender stereotypes and enforce the notion that men should be dominant and women subservient and submissive. Justifications for violence are frequently based on cultural and social norms that socialize males to be aggressive, powerful, unemotional, and controlling and women to be passive, nurturing, submissive, emotional, powerless, and dependent on men. This unequal power relationship between men and women is reinforced by a number of factors, including the Armenian schooling system and mass media. School textbooks encourage young girls and boys to keep to their traditional gender roles, in effect normalizing and perpetuating gender stereotypes. Widely viewed Armenian soap operas depict women as beaten and cheated upon, reinforcing the cultural acceptance of gender-based violence. When played out in real life, these gender roles take on a sinister tone in situations of abuse, translating into a learned behavior whereby few women leave abusive husbands and perpetrators believe that their actions are not out of line. This common acceptance of domestic abuse hinders women’s ability to live in safety and perpetuates the cycle of violence.

Domestic violence is a multi-dimensional problem that requires integrated and coordinated responses at all levels. Armenia desperately needs a well-functioning referral mechanism among law enforcement, civil society, health care providers, child protection services, educators, the media, and other actors. While the Armenian legal system differs from the US context, there are certain ethical considerations that should be universal, such as the right to a fair trial and judicial impartiality. There were clear ethical violations at the aforementioned trial. Judge Balayan demonstrated gender insensitivity and, at times, belittled the victim.

As the issue of domestic violence in Armenia is steeped in a strong patriarchal tradition and stems from harmful gender stereotypes and a cultural acceptance of gender-based violence, a greater emphasis on primary prevention is vital for a paradigm shift to occur. The government must be kept accountable for fulfilling their commitment to combat DV. We urge the State to comply with its international obligations by adopting a standalone DV law; carrying out comprehensive trainings with specialized service providers, including law enforcement officials; supporting DV shelters; and carrying out public campaigns, advocacy, and educational initiatives. Only when victims are properly assisted and perpetrators punished will the public receive the clear message that domestic abuse is a serious crime that cannot and should not be tolerated. We cannot wait by the sidelines as more women in Armenia are beaten, tortured, and murdered. We must act now.