Immigration: In the Armenian transgenic memory this word likely echoes sojourner, diaspora and exile as words prescribed to immigration in the pages of history. Even though it is known that no two immigrations are the same, it is also known that they have a common core, one that is of separation. This is when a new form of identification lies ahead, one that needs to walk through fears of separation, yesterday’s and tomorrow’s loves and hatreds, emotional bankruptcy and ambivalence.

The Russia-Ukraine war started on February 24, 2022.

Since then, many Russian citizens have fled Russia, some to Armenia.

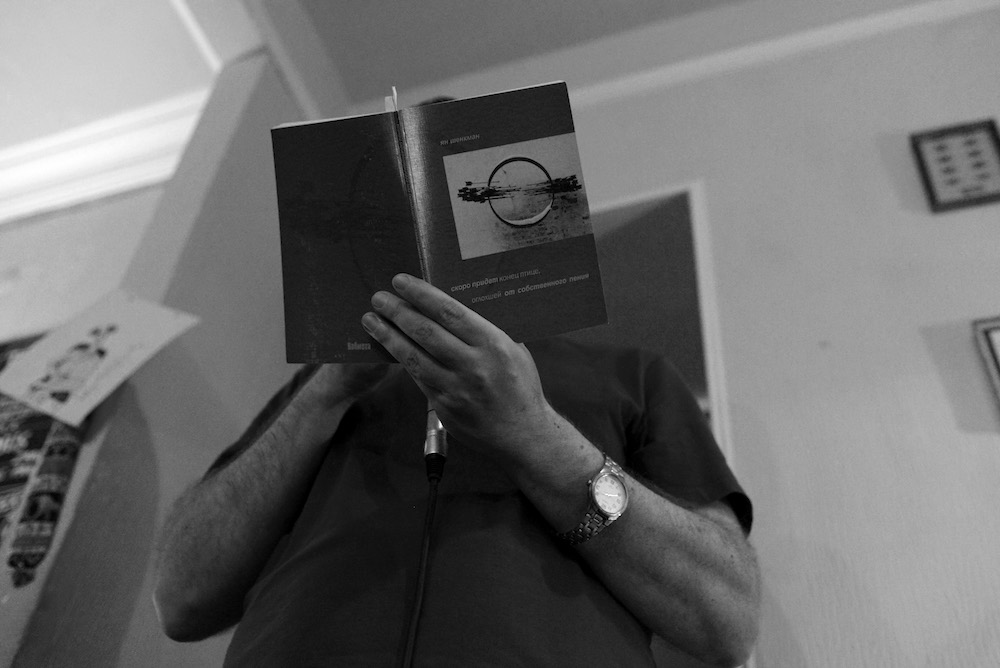

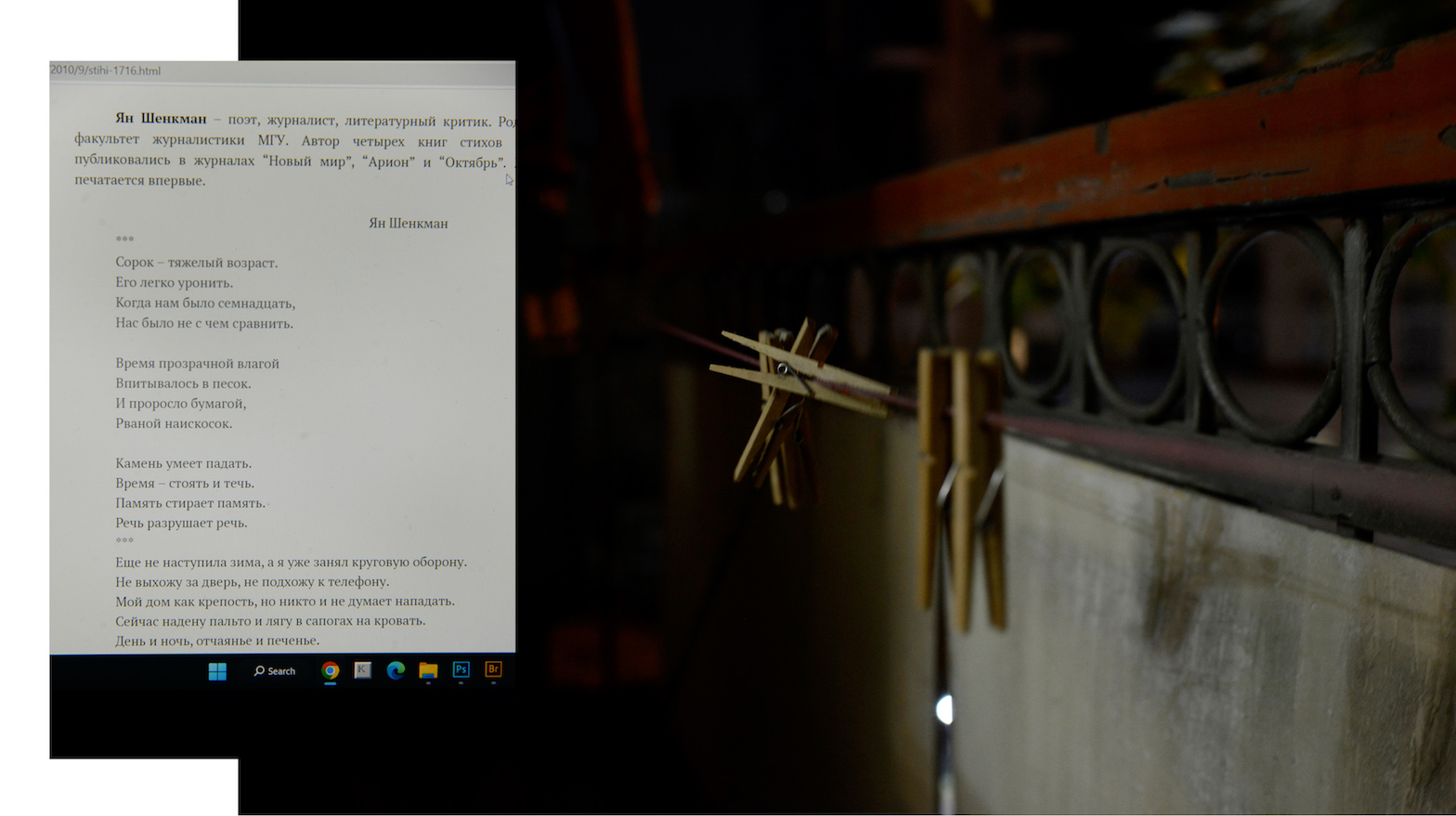

Yan Shenkman

Writer, journalist

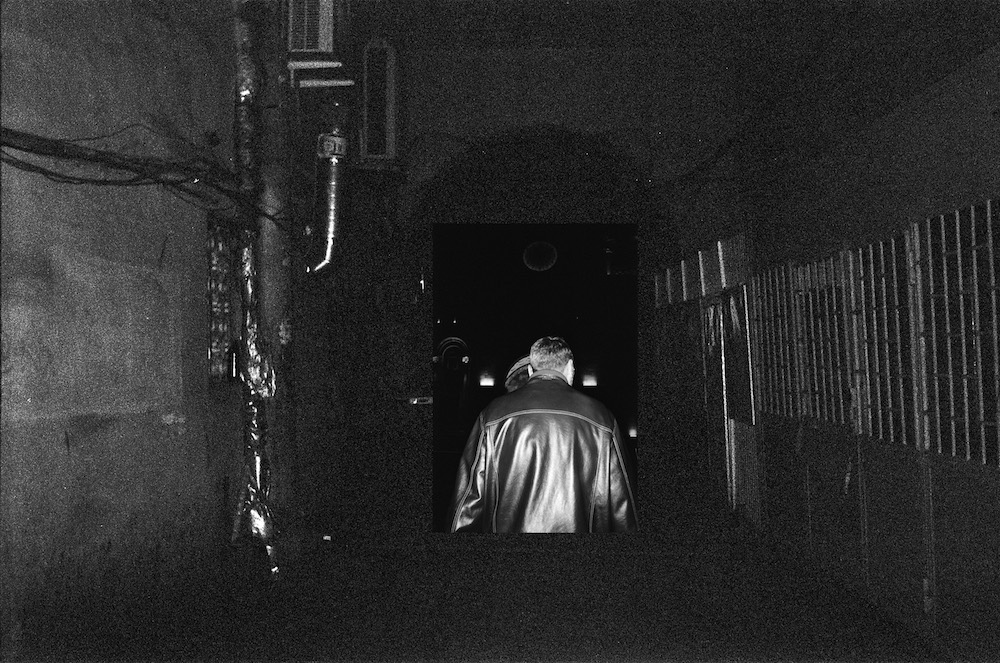

I never planned to leave Russia, but on February 24 of last year, I understood that after this disaster, life as we knew it was done with. It was a feeling of total defeat, when you understand that you have utterly failed.

Psychologically, my life was complicated before the Russian-Ukrainian war, I was working for an opposition media. In contrast to many of my compatriots, I was aware of the negative developments in our country. Being in my line of work was nerve-wracking. Besides your own emotions, you have to promptly respond to fast changing events and sometimes there is no time to analyze what is happening and the dangers that these developments present and you find yourself at the pressure point of these developments. It was also difficult in the sense that you or your colleagues understand the gravity of the situation but as far as most of society is concerned, everything seems to be fine. This is a paradox. You start yelling louder about the disaster but are told that there is no such thing, it is your imagination. For ordinary people, you are up to no good, you are making things up. You pointlessly waste time and emotion. This kind of a contradiction leaves a very negative mark on your psyche. However, the motivation to stay was still there. Me and many like me were trying to bring change. When you see that someone needs help and you can help to a given extent, that is what you set out to do. We needed to take measures, publish anti-war articles… as long as these were possible, I stayed. With the start of the war, all my roads closed.

This does not mean that all roads were sealed off or were closed for all, but they were for me. If I were a doctor, I would have stayed, I would not have considered leaving. In all my paperwork I write down that I have left because of the impossibility to carry out my professional duties. Articles continue to be published in Russia about elite living, computer games, healthcare but journalism is a profession that is closely intertwined to one’s essence. I could no longer do the reporting that I used to do. Even if I wanted to, I could not change gears and go work in some other local media, resign my ideals, I could not. No one would have hired me with my resume anyway. This is not the loss of connection with Russia but rather with a life ideology. Not unlike after the fall of the Soviet Union, when the ideology changed and it was no longer useful for anyone. Attempts to resurrect a corpse are futile.

The other reason why I left was fear. I was afraid of the extremely unhealthy, agitated and aggressive environment. I was afraid I would not be able to withstand it, that it would break me. Very few write about it but during the first months after the war, the psychiatric wards in Moscow and St. Petersburg were full of patients. People were not able to endure. It would have been different when it comes to feelings of guilt, responsibility and public stance, if the tragedy was different, if you were the one attacked, at least in that case you do not represent the evil side.

The first couple of months after arriving here were difficult, not because of what I had lost; I had come to terms with loss from the beginning. But had I made the right decision? The most difficult part was the uncertainty of the future. At the beginning, many of us did not know where we were going to end up, how and where we would live in this new place especially given the lack of documents. The unknowns were too many. But with time, more small lighthouses appeared, more support was available. There were things to hang on to, new acquaintances, or someone would find an apartment to rent, another would find work, yet another would figure out their peril with documents or solve another unknown.

There are immigrants who wish to return. I think this is not so much about patriotism as much as it is a matter of habit. This is a wish to return to a known environment, to a home, to friends, to the familiar. These are bonds that are hard to sever. It was easier for me, I’m alone, I do not have a family and my parents have passed away. Over the first months, many had this habit that was known as “weekend immigration”; this is when people would go back to Russia a couple of times a month just to be able to overcome their issues with acclimatization. Those who simply went back are not few in number either. They decided that they had made a mistake by leaving. Others were more practical, they looked for jobs, put their documents in order, put a business plan in place beforehand… unlike me, I left with one suitcase. But the truth is, even more than a year later, most do not know what they will be doing. One of the psychologists says, “Patients say they have Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, but I explain that they can not have PTSD since the trauma is still ongoing. Nothing is over.”

This is a specific situation, many can’t start building new lives so long as the disaster continues and not only between Russia and Ukraine but for the whole world. The fear is that the minute they start building anything, everything will change again. We are not in post trauma, we are in the trauma itself. In this respect, Armenia has been very therapeutic, people here have been in the worst situations for over 30 years and yet are more calm. I have not witnessed hysteria or emotionally charged behavior here. The locals have either learned to live in stress or maybe they do not show their emotions.

I had visited Armenia a couple of times before. I have some ideas about the country. I have been to the mountains, seen the monasteries. Everything is beautiful of course but I’m not a particularly visual person. The food is also tasty, still back in Moscow I used to go to Armenian restaurants and enjoyed the cuisine. In that sense food is not exotic for me, not a novelty. It was the people here that made the biggest impression, not nature or food.

My heightened state of stress and people’s response were almost in contradiction. People do not tend to escalate the situation, to turn things into a conflict, they calmly settle things. The softness of this attitude, which might be a national trait, made an impact on me.

When they say emotions are heightened in the Caucasus, that people shout and fight or that they express their emotions loudly, it is a myth. For the counter-argument, go to the Gum Market, it is quiet there, everyone is calm, correct and dignified. Compare Gum to the Pryvoz Market in Odessa, where they shout and pull from your arms and you’ll see there is not much of a similarity. This is one of the myths about the Caucasus that has no truth to it.

Even though I knew well that there are many Armenians in Russia, I still did not clearly understand that Armenia, not being a Slavonik country, had such subtle ties to Russian culture. Many here act with such cultural sensitivity that you forget sometimes that you are in a completely foreign cultural space. There were many similar paradoxes. All the countries in the Caucasus naturally carry a common Soviet trace, but Armenia seems to have preserved an important component of that era, the warmth of communality.

Armenia has the illusion of being somewhat archaic, Soviet or having a 1990s vibe, it makes you feel like there is a way back to the point beyond which everything started to crumble. It seems like it is behind on some things but in reality, it is stuck at a point that still carries fond memories. I keep seeing carpets, books, and other things that are familiar to me from before. A house I rented had the exact same carpet on the floor as the one I used to play on when I was a child. Doubtlessly, the cultural environment is unique, the language, the music, everything else is different and yet there is no sense of unfamiliarity.

Armenians as well as the Jewish people in Moscow are often well-to-do doctors, artists, intellectuals and teachers. But that narrow environment, the specific community does not necessarily give you a perspective on the nation.

Here, when you communicate with the people, you understand that not all Armenians are surgeons and stand-up artists. You find out that even the uneducated people carry over a part of an ancient culture. People here are nothing like the Armenian characters in jokes.

However, there is something that bothers me and I understand that I will have to live with that – I will never understand that which Armenians know. When one says to the other, “Remember that?”…I will never know what it is about. People who were born here, grew up here, went to school, lived through the devastating 90s, the first war, the second war, I will never have those experiences.

This is not a regret born out of my love for suffering, I regret that I will never be able to understand the shades of your experiences. But this would have been the same in any other country. The tragedy of immigration is not so much in the loss of something but in being a stranger somewhere for the rest of your life.

There is the belief that at the beginning the immigrant experiences some form of euphoria, they like everything at first. That is not necessarily true. I know people who at first and for the longest time, for about half a year, were suffering. They were depressed, unable to leave their beds. Others had that euphoria, but it was short-lived. They too got depressed, they got “homesick.” In that sense, it is easier for the young, it is easier for them to accept the new and they cling less to the past.

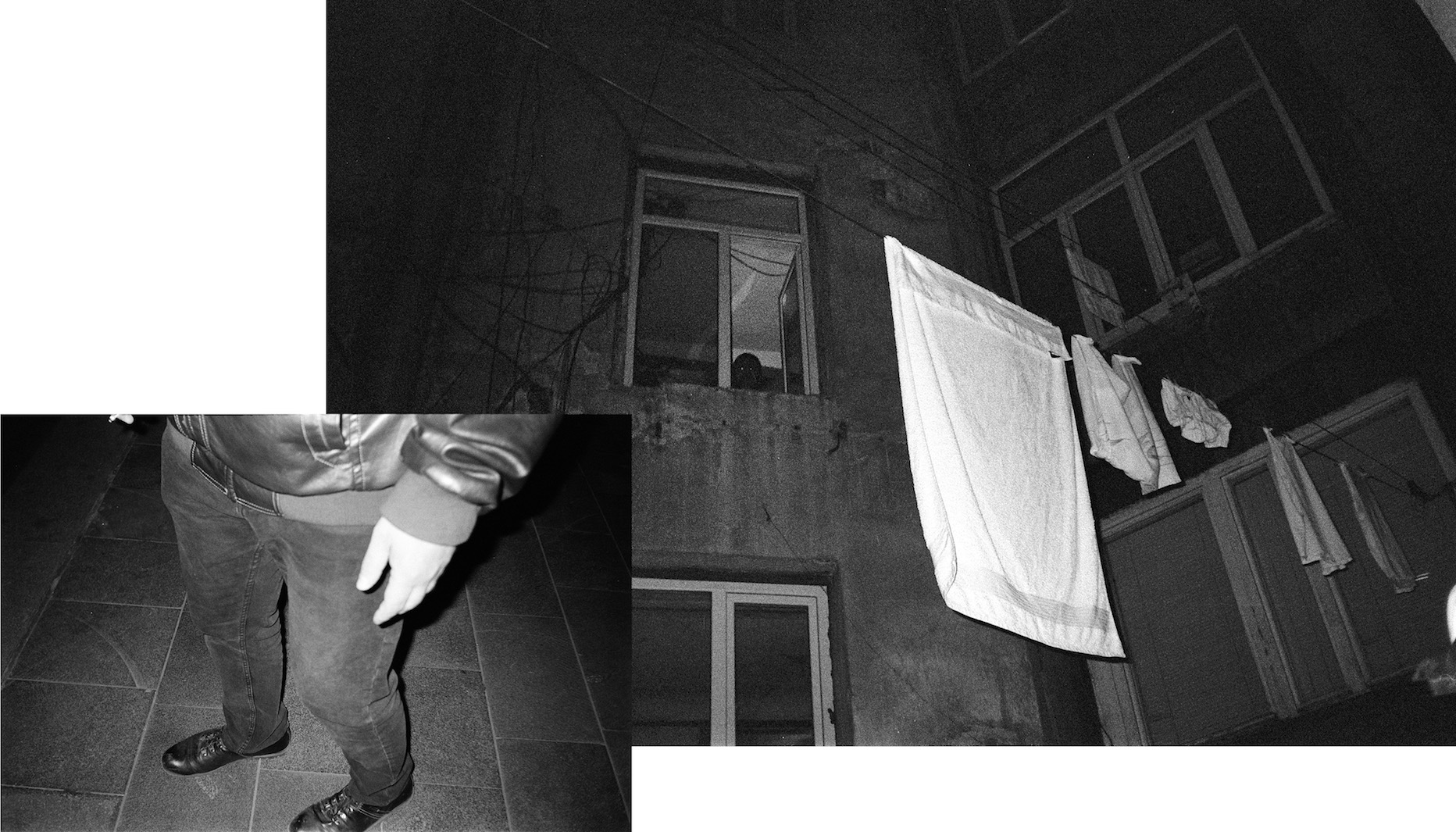

One time, when I woke up in the middle of the night and in my half-woken state I automatically reached for the light switch and I couldn’t find it. It wasn’t where it had always been at home in Moscow. For a moment, I didn’t know where I was. This felt painful to the point of tears.

At the beginning there was fear, this was a human kind of fear, not political. When you live in a constant state of fear, you perceive it as the norm but when you see that it does not have to be that way, you wonder: What was happening to me before? And fear gradually starts leaving you. A person in a new space acts more carefully. This is true for when you are at a store or at home.

One day there was a cat at the entrance of my building and it didn’t run away when I approached, the cat just stayed. And cats always run away. This one was so confident that no one would hurt it. Cats and dogs at the center of Yerevan continue to lie where they please, it is you who needs to go around them. They are absolutely certain that they are safe. And that is when I thought — even the cat is not afraid. It is also interesting that no one checks your documents here on the street. Organizations can also just trust you. I have no recollection of anyone pushing me on the street.

It was relatively easier for me. I adapted quicker, found work, new acquaintances, and regulated my routine. I understood that the first phase of survival for me was pretty successful. But then again, whenever faced with an extreme circumstance, you tense up and concentrate all your energy on one thing. This is no way to live a life. And the question arises, then what? I’m in that stage.

At this stage, the colors have begun to fade for me and this comes with its own set of complications. Decisions need to be made, a long-term plan needs to be found. For many, after the euphoria, things start tasting sour. At first there is relief, you have averted trouble, you at least have a roof over your head. Then nuisances emerge, something or another is not like what you are used to in Moscow, nothing works, there are no perspectives. But that is how things would have been anywhere, there are no ideal countries. The answer is clear, this is not Moscow, this is Yerevan, why would things be the same? I like the fact that things are different here. The everyday issues, the unusual slowness, the lack of certain accommodations… These things are of little concern to me. And if some things that Moscow offers are not available, then other things are bound to be created here.

People striving to preserve their former lives is something that bothers me. There has been a disaster of considerable magnitude, people are dying, everything is falling apart and if after this point life continues as it was, as if nothing has happened, then all of this was for nothing. The only saving grace after what has happened would be if we start living differently.