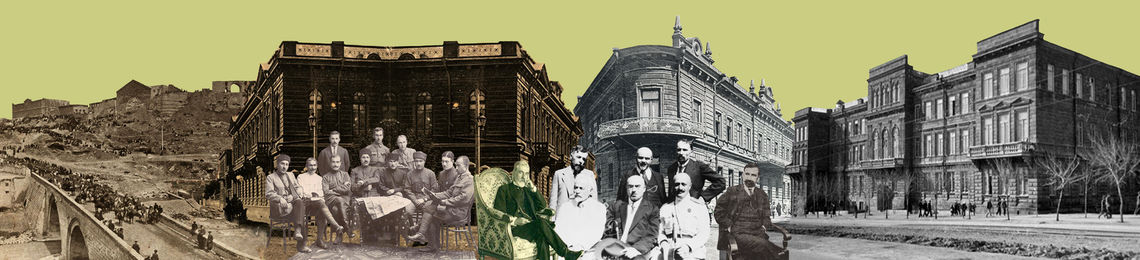

Aram Manukyan announcing the Armenian Republic; A painting by K.S. Shahbegian, 1965. (fig 1)

Gauging current public perceptions can be done through various ways. On the eve of the centennial, the number of debates, social media posts, and newspaper editorials are on the rise, providing us with ample material to have a clear idea of the larger picture. Using a wide array of material from social media, pictures, and printed articles, this work addresses four major themes, namely, the First Republic as a new political category, the problem of historiography, the role of education in the Diaspora, and the effects of these three on shaping public discourses about the Republic.

Shahbegian’s portrait of the First Republic (fig 1), a fascinating painting in itself helps us visualize some of the major questions that I will be tackling throughout this essay. It beautifully captures the four above mentioned themes, and thus constant reference to it will be made throughout the article.

The First Armenian Republic: A New Category?

What is the Armenian Republic? This question seems to invoke a rather easy answer, a historical problem to be more precise. Yet, it is much more complex than that. The establishment of an Armenian Republic introduced a new category in Armenian political thought, that of a Republic, a phenomenon that awaits its full appraisal in Armenia and more particularly in the Diaspora. Oftentimes, we represent the creation of the First Republic as the reemergence of the lost Armenian statehood, yet we rarely reflect on the intellectual corollaries of this potent term: State, L’Etat, Պետականութիւն. Are the state and the homeland the one and the same? Should they be so?

The term “Armenian Republic” itself, often taken for granted (epistemologically) necessitates further deliberations. Whereas the “Armenian” may capture the totality of “Western Armenia,” Cilicia, Javakhk and Artsakh, the “Republic” is a set of institutions and a mode of governance. The idea of a “state” may be inclusive of the “homeland,” yet it does not always work the other way around. I have tackled this issue in a different article and will not elaborate more here. Yet, it is important to reiterate that the state invokes a legal, and a political category that contains an objective truth, whereas the term “homeland” may invoke or appeal to different subjectivities, such as sensibilities of loss, or geographical imaginations that may stretch from Sasun to Shushi.

Symbolism, abstractions, and romanticism tend to overshadow the ontological reality that Armenia is an independent, internationally recognized, geographically demarcated, and a sovereign state with its political, legal, and social institutions. This then leads to political imaginaries among many Armenians that often regard the Armenian Republic as an “incomplete Armenia” implying thereby that there are still some “redeemable lands,” Thus, the primary question around which most debates revolve is “How did the Armenian State come to be?” without fully integrating the “What are the foundations that are necessary for the stability and the survival of this State?” This is particularly poignant in the Diaspora, as its sheer nature and the staunch anti-Soviet stance of the ARF throughout the Cold War have conditioned a considerable proportion of Diasporan Armenians to alienate themselves from what came to be known as the current Republic of Armenia.

Of course, it goes without saying that the above mentioned phenomenon of selective historiography found deep roots in the educational system of the Diaspora. Partisan affiliations and/or ideological commitments have often impacted the content of history textbooks that are used in Armenian schools. Thus, Armenian history textbooks have turned into timeless objects reflecting this linearity with a strong emphasis on the “spirit” or the “soul” of the nation as the prime mover of its trajectory towards its predetermined end. History classes in most ARF affiliated schools thus reinforce conventional narratives and paradigms, with particular focus on Party history, the Genocide, the First Republic, and the Artsakh Movement from 1988-1994 omitting thereby a 70-year period of Soviet-Armenian history and the post-1994 developments. History thus becomes a tool for identifying heroes or receiving communion rather than equipping students with the critical abilities to understand, and assess changes, ruptures, continuities and transformations.

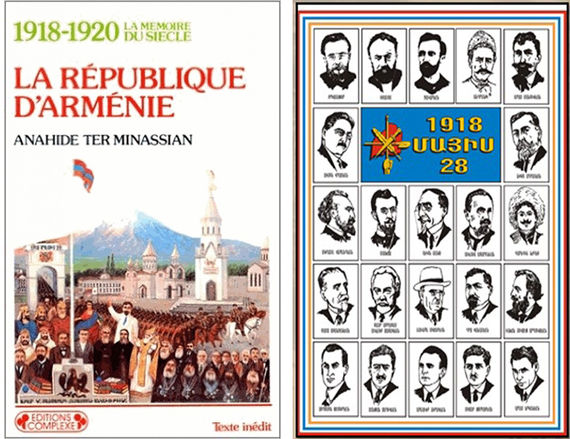

(fig 2 & 3)

(fig 4)

(fig 6)

(fig 7)

From an ARF perspective, the situation is not much better. Sympathizers of the ARF refuse to recognize Soviet Armenia as the “Second Republic,” castigating it as foreign occupation. Therefore, instead of the now conventional way of depicting the period 1918-1920 as the first, 1920-1991 as the second, and the post-1991 as the third republics, ARF officials and affiliates make the giant leap from First to Third (marked as Second) without recognizing the strong impact of the second (Soviet). This is another manifestation of the problem I discussed in the first section, namely the difficulty of grappling with a new political category, that of a Republican state. If we were to explore the institutions that governed and sustained the first, second and third republics as republics per se, the fact that there exist major continuities (as well as breaks) among the three becomes indubitable. Therefore, more than debating whether Sovietization is tantamount to foreign occupation, it behooves us to discuss the institutional changes, transformations and parallels among the three republics. It is through such an appraisal that we would be able to evaluate the impact of new epistemological categories on modern Armenian political thought.

The February 18 uprising of 1921 against the Bolshevik authorities and its repression by the Red Army in Armenia is one of the most contested episodes in the early history of Soviet Armenia. Whereas Soviet-Armenian historians tried to describe this revolt as a “bourgeois-nationalist” reaction against Bolshevik socialism, ARF sympathizers still commemorate it as the party’s last heroic attempt to “save” Armenia from foreign or even “tyrannical” rule. A quick glance at ARF affiliated newspapers in the Diaspora will give us a sense of this phenomenon. While rarely does the Armenian media (in the Republic) remember the February events, ARF circles in the Diaspora perpetuate a manichean discourse through which the “good” and the “evil” are clearly discerned. The editorial and articles titles below are just a few examples of this trend. [The February Uprising Became a Barrier Against Dictatorship (1)], [The Last Heroism of the Fedayis (2)], [February 18: A Tragic End to a Promising Beginning (3), [The Majesticity of the February 18 Uprising (4)]. (fig 4)

The Cold War has provided the anti-ARF camp with a few “classics” that are often used to criticize the ARF (whether in the Diaspora or Armenia proper) and tarnish its reputation. Hovhannes Katchaznuni’s “The ARF Has Nothing to do Anymore” [Դաշնակցութիւնը այլեւս անելիք Չունի] is the most well-known and common. Written by one of the former prime ministers of the First Republic, and an ex-member of the ARF, his book with its “excellent” title (a ready weapon from an anti-ARF perspective) is often decontextualized to address contemporary problems and launch polemics against the ARF. An article published in Armenia during the “Sasna Dzrer” turmoil in the summer of 2016 and titled “Really! The ARF has nothing to do anymore” an obvious play on words of Katchaznuni’s work, is yet another manifestation of this trend (fig 5)

The second example is K. Serop Papazian’s Patriotism Perverted, a strong opprobrium against the ARF published in 1934. Although the book was produced against the background of the assassination of Leon Tourian in New York in 1933, an event that deeply divided the Armenian-American community (the scars of which are still felt today), its strong anti-ARF polemic has rendered it into one of the tools upon which anti-ARF discourses rely. Thus, it comes as no surprise that the book has found its way into anti-Armenian Turkish online forums and websites. The phraseology of Papazian’s narrative is often reproduced in contemporary debates with little alterations. An excerpt would be elucidating: “The task of presenting the Dashnagtzoutune [ARF] in its true political and moral character was rather difficult, as this society has had the agility of repeatedly changing its face and color with perfect ease of conscience. At first, they were nationalists diluted with socialism; then they turned out and out socialists, with Bolshevistic leanings, and adopted the red flag for their emblem. However, it co -operated with the imperialistic tyrants of Turkey.”[5] The expression “Bolshevistic leanings” is bolded to show the parallels with Narine Tukhikyan’s recent statement regarding ARF officials in Armenia. In a response to the former Minister of Education and ARF member Levon Mkrtchyan’s calls for giving Russian a special status in the Armenian educational system, Tukhikyan, the director of the Tumanyan Museum claimed that Mkrtchian and the ARF leadership of Armenia are Neo-Komsomols. Although uttered in a totally different context, Tukhikyan’s words are reminiscent of Papazian’s polemic. (fig 6)

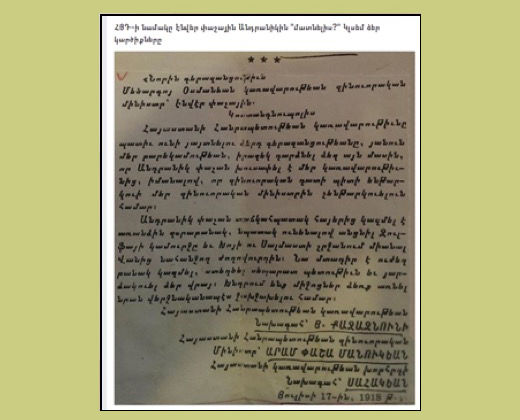

Throughout much of the 20th century, in their ideological and actual struggle against the ARF organization in the Diaspora, the Soviet authorities engaged in an active process of fabricating documents that were used to taint the ARF’s reputation among the Armenians. One of these “notoriously famous” documents has re-emerged on social media recently. It is a letter sent to the Ottoman War Minister Enver Pasha in 1918, and supposedly signed by Aram Manukian and Hovhannes Katchaznuni, asking the former to collaborate in order to “get rid of” Andranik Pasha (Ozanian), the pioneer of the Armenian revolutionary movement in Armenian public perception. (fig 7). Despite the fact that the director of the Armenian National Archives, Amadouni Virapyan has demonstrated that the memo in question is a forged Soviet paper, its constant reappearance through social media posts and the polemical debates that ensue is another testament to the Cold War legacy.

The contestation over national symbols continued yet in another domain, namely the new Dram currency that the Armenian government decided to issue on the eve of the centennial of the Republic. Not one single figure from the history of the Republic was/is depicted on the new Dram, which sparked a wave of criticism that many ARF sympathizers and otherwise rightfully voiced. The selection of a few characters such as William Saroyan and Hovhannes Aivazovsky irritated many ARF affiliates to an extent where statements were made claiming that the Central Bank of Armenia was unaware that 2018 was the centennial of the Republic, as is shown in the picture (fig 8).

(fig 8)

Conclusion