As a tour guide, I get to travel a lot throughout Armenia. Since I’ve spent my teenage years in the U.S., I also tend to look at some things from a viewpoint of an outside observer. One of the things that I’ve noticed is the near-omnipresence of Stepan Shahumyan. Statues, streets, villages and towns are named after him in Armenia and Artsakh. But who is Shahumyan and why is he still remembered by Armenians?

Shahumyan was one of the most prominent revolutionary socialist activists in Russian Transcaucasia in the early 1900s. Amid post-war turmoil, Shahumyan founded the first Soviet-style government in the Caucasus—in Baku, a proletariat-dominated industrial oasis in an overwhelmingly rural region. He led the attempt to establish a “dictatorship of the proletariat” in the oil-rich city. The Baku Commune (inspired by the Paris Commune of 1871) lasted only three months in 1918, but it provided a major morale boost for Marxists of the Russian imperial periphery. Naturally, he was glorified by communist historians and was dubbed the “Caucasian Lenin.”

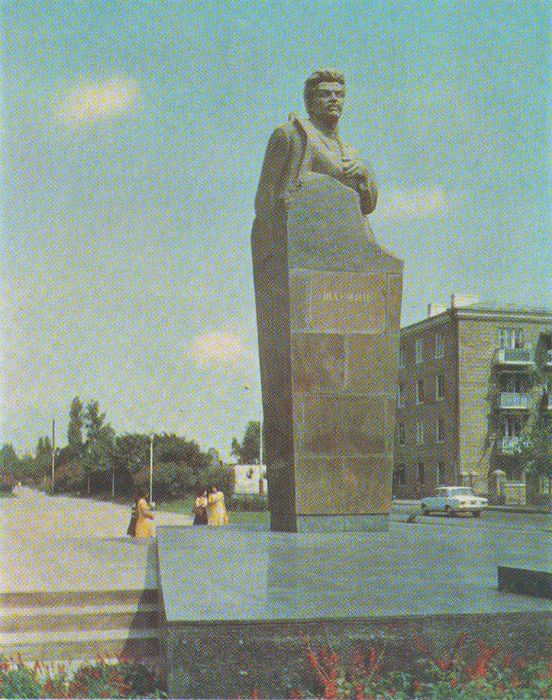

The monumental memorial to Shahumyan, erected in 1931, was the first statue in Soviet Yerevan. Standing at a central square with a backdrop of a grey basalt colonnade, it replaced a Russian Orthodox church, which had been demolished just years earlier. The demolition of the church and its replacement with the statue of a communist “martyr” reflected at least two ideals of Soviet ideology—“militant atheism” and the public display of Marxist fighters. Created by the prominent Greek-Armenian sculptor Sergey Merkurov, his statue in Yerevan still stands in Shahumyan Square, between the newly constructed government building and a business center housing the headquarters of Ameriabank, just 200 meters off Republic Square.

Armenia chose a different path from some of the Eastern European and post-Soviet states that moved their communist statues to secluded parks (e.g. Hungary, Lithuania). As a rule, non-Armenian communists were removed from public spaces (e.g. Marx, Lenin, Azizbekov), while statues of ethnic Armenian communists remained intact (Shahumyan, Alexander Myansikyan, Gai, Suren Spandaryan). Lenin’s statue in Republic Square was ceremoniously removed in April 1991 and thereafter partly destroyed. In an absurd display of inconsistency, Spandaryan Square in Yerevan was renamed after Garegin Nzhdeh, a staunch anti-communist, while Bolshevik Spandaryan’s statue was left standing in the square.

Ashot Voskanyan, who teaches a course on Soviet Armenia at the American University of Armenia, looks at Shahumyan in the context of post-Soviet identity and perception of historical memory. He argues that Armenia is inclusive in its approach. Essentially, Armenians tend to look at both nationalist and communist politicians as equally Armenian and view the Soviet Armenian republic (1920-91) as the “second republic” and a continuation of the first (1918-20). Georgians, our neighbors to the north, define their identity by excluding and rejecting their Soviet past. A Museum of Soviet Occupation was founded in Tbilisi in 2006.

Voskanyan, a former MP and diplomat, suggests that Shahumyan does not have the same controversial image that the prominent Armenian Soviet official Anastas Mikoyan does. A statue of Mikoyan was supposed to have been erected in Yerevan in 2014, but was cancelled after an uproar regarding his role in the Stalinist purges. Interestingly, Mikoyan was the sole survivor of the 26 Baku commissars, the group led by Shahumyan.

For Armenians, Shahumyan is a “construct rather than a real-life figure,” says Voskanyan. He argues that it is hard to evaluate Shahumyan’s role as he never had a chance to actually rule besides the brief Bolshevik experiment in Baku. Voskanyan, primarily a philosopher, notes that Shahumyan’s analytical and theoretical articles of the early 1900s are worthy of praise for their critical approach to the national issue. Shahumyan repeatedly denounced the “bourgeois nationalist” Dashnaks for failing to address the economic conditions of Armenians and for distracting them from class conflict.

Now, a century later, the Dashnaktsutyun (Armenian Revolutionary Federation) overlooks those attacks. Shahumyan’s historical arch-enemies portray him in a more positive light now, perhaps, having the animosity with the Azerbaijanis in mind. “Although Shahumyan was not directly involved in Artsakh, he is one of the few Bolsheviks who had a national face. Shahumyan founded an Armenian state in the territory of today’s Azerbaijan, namely Baku,” says Vahagn Dadayan, spokesperson of the ARF in Artsakh. Calling the internationalist commune in Baku an “Armenian state” may be a long stretch, but post-Soviet Armenians focus on the capture of the city by Ottoman forces in September 1918, after the demise of the commune and the massacre of Armenians that ensued. Consequently, the commune is, retrospectively, seen as a protector of Baku Armenians during the time it controlled the city and its environs.

In Karabakh, the hotbed of Armenian-Azerbaijani animosity, the regional capital was renamed Stepanakert after Shahumyan in 1923, just five years after his death. Shushi—the center of Karabakh Armenian life—was burnt to the ground in a 1920 attack by Azerbaijanis. To make Stepanakert, a city named after an ethnic Armenian who first established communist rule in the Azerbaijani capital, the regional capital, was nothing more than an attempt by the Soviets to promote the fraternity of the two peoples. After all, Shahumyan was a committed internationalist and a staunch opponent of ethnic nationalism. Reflecting on the Artsakh ARF’s official stance, Dadayan believes that “there is no need to subject this period of our history to inquisition” and rename the city.

While Armenians tolerate and even celebrate Shahumyan’s presence in public spaces, Azerbaijanis have not been as kind due to rampant anti-Armenian sentiment. Not only was his statue in Baku removed, but in 2009 his body “disappeared” in the process of reburial of the 26 Commissars of Baku, the group Shahumyan led in establishing Bolshevik rule in the city. Shahumyan’s commune there was eventually deposed, bloodlessly, by a coalition of anti-Bolshevik leftists (including the Dashnaks). The Commissars, including Shahumyan, were later taken to what is now Turkmenistan and executed there by the British interventionists and Russian Socialist Revolutionaries (Essers).

The ghost of Shahumyan still wanders through his native Caucasus and Armenians have largely forgotten his century-old verbal attacks on nationalism and insistence on internationalist fraternity of peoples that seem so discredited now. Simultaneously, his stature, aggressively promoted by the ancien régime, has become largely irrelevant in today’s Armenia. In north of the country, in the town of Stepanavan, where Shahumyan founded the first Marxist group in (Russian) Armenia at the turn of the century, a museum dedicated to the Bolsheviks was turned into a cultural center after Armenia’s independence. The daily Aravot recently mourned the state of Shahumyan’s bust in a remote village in Tavush: “The snow on Shahumyan’s monument has not been removed, no flowers are placed on the statue of the great party and national figure, and, probably, has not been place for a long time.”